Song For My Father by Horace Silver

I’m a Kiwi who’s lived in London since 1991 and the pandemic made me both yearn for and fear for my family, so far away. To calm my huge angst, especially when my father’s health collapsed in March, I listened to music constantly, obsessively, jazz serving as a balm to my worried mind. Dad died in late June, not of the virus – a fall led to him departing this world. I mourned and celebrated his life with music, especially Horace Silver’s funky, warm eulogy to his father. Released on Blue Note in 1965, Silver’s instrumental reminds me of great jazz clubs in London, New York, Havana, and of the old fella – even if his musical enthusiasms never moved beyond Gilbert and Sullivan.

This Man by Robert Cray

Robert Cray released That’s What I Heard in February 2020, a superb album, and I planned to see him play at Bexhill’s De La Warr Pavilion in April: a trip to the seaside with an evening of blues in a modernist pavilion – pretty much a perfect day. Obviously, the concert never happened but the quiet fury of the album’s most intense song, This Man – about an unnamed thug in “our house” who needs to be voted out – resonated across lockdown, articulating the struggle for the soul of America then under way. Dignified, angry and beautifully felt, Cray’s music kept me focused when the world seemed to be slipping into darkness.

West End Blues by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five

Louis Armstrong is a constant in my life, his music (and spirit) always accompanying me whether I’m home or away, the sound of Satchmo so wonderfully reassuring. Ever more so over lockdown: if you could bottle joy it would be Louis Armstrong. His warmth, soulfulness, the way his trumpet caresses notes, the chuckle in his voice … West End Blues, recorded in 1928 when Louis was establishing himself as jazz’s foremost genius, makes me think of good people and good times I’ve encountered while travelling across the US. Clubs, bars, juke joints, honky tonks, festivals, street performers – the sound of American music can be so liberating, never more so than when Satchmo starts to blow.

Chaje Shukarije by Esma Redžepova

Most summers I venture into the Balkans, Europe’s own deep south (beautiful music, ugly politics), and North Macedonia is where things get really hot. Locked down in London I dreamed of Skopje, that battered brutalist city with Shutka – the world’s largest Roma community – on its northern border, home to stunning Gypsy brass bands and much else. Esma Redžepova was North Macedonia’s greatest singer, her majestic voice ensuring she was celebrated as “queen of the Gypsies”. I got to spend time with Redžepova when researching my book, Princes Amongst Men: Journeys With Gypsy Musicians, and she was never, ever less than fabulous. Chaje Shukarije (Beautiful Girl) is a song Esma wrote aged 13, her first hit, and now a Balkan anthem.

Southern Nights by Allen Toussaint

New Orleans is my favourite city on Earth. Unable to visit in 2020, I revelled in its music, its sensual, unhurried charm, especially that of the city’s magus, Allen Toussaint: pianist, songwriter, producer, arranger, performer, he was a phenomenal talent. Once, when visiting, I saw Toussaint standing on the sidewalk beside his cream Rolls-Royce. I rushed up and declared my devotion. To which he gave a regal nod. Glen Campbell had a huge hit with this Toussaint tune but it is Allen’s version, one he always performed in concert, that conjures up Louisiana’s humid mystery and Creole communities. Learning that Robert E Lee Boulevard will be renamed Allen Toussaint Boulevard was a bright spot among 2020’s blight.

It Mek by Desmond Dekker & The Aces

In pre-pandemic times I loved digging for old ska and rocksteady 45s in Brixton’s reggae record shops. Desmond Dekker was the first Jamaican artist to reach number 1 in the UK charts (in 1969, with Israelites) and is my all time favourite – listening to him transports me to a journey I made along Belize’s Caribbean coast: here, in shantytowns, sound systems played old reggae and soul tunes (and Simply Red!) and people danced in the rain. It Mek sounds effortless, as if created in a beach bar, everyone dancing as Desmond struts through the song. While I have no idea what Dekker’s singing about, the song makes me smile as I attempt sit-ups and stretches, fighting lockdown flab with reggae rhythms. What a groove and what a tune!

Home Is Where The Hatred Is by Esther Phillips

Aged 14 in 1950, Little Esther was the hottest R&B singer in the US. Four years later she was burnt out and in the grip of heroin, and across the rest of her too brief 48 years, Esther Phillips would experience both high times and hard times. Gil Scott-Heron wrote this brutally direct ode to addiction but Esther owns it, singing with a furious hurt few have ever matched: she was Grammy nominated for this 1972 masterpiece, losing to Aretha Franklin – Aretha then insisted on presenting her award to Esther! Listening to Phillips sing, her voice so desperate, I’m reminded of my travels through Asia, specifically Calcutta and Delhi, huge, heaving cities where, for many, life is lived extremely close to the edge. Over lockdown, Esther’s unflinching artistry, honesty and refusal to quit when everything appeared impossibly bleak inspired me. Fail better? Few have ever matched Phillips in doing so.

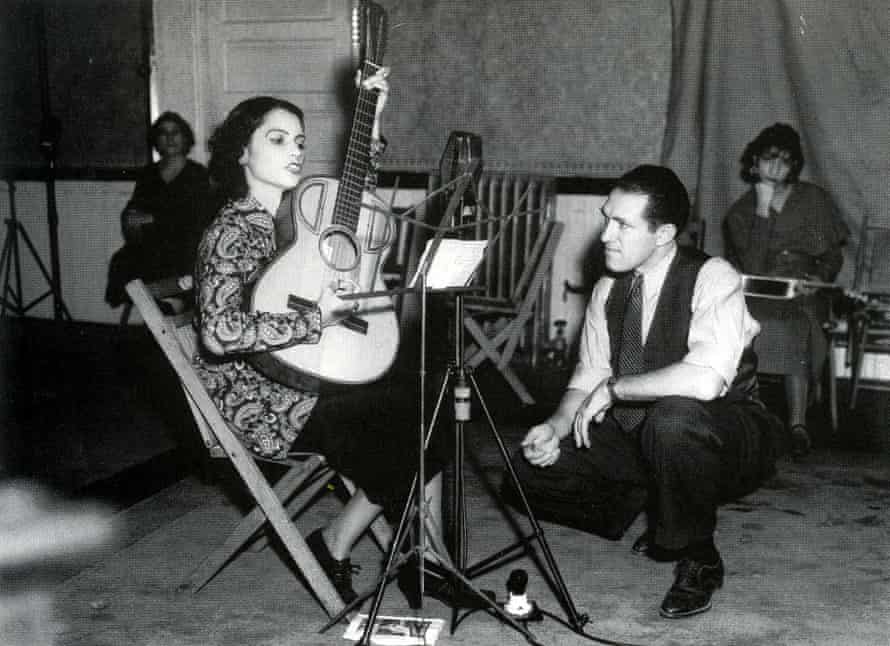

Mal Hombre by Lydia Mendoza

During the pandemic I have watched more TV than ever before, with nothing matching Narcos Mexico for intense narrative drama. The series also appealed to my love for Mexico and the fluid culture of the Mexican-American borderlands that produced Lydia Mendoza, a singer and 12-string guitarist who, as a teenager in the 1930s, became the first star of Tejano music. Some 70 years later I met her in San Antonio, Texas, while researching my book, More Miles Than Money: Journeys Through American Music. By then a stroke had left Mendoza disabled and so unable to make music – a cruel punishment – yet Lydia spoke proudly of her many achievements. Here she sings of a bad man: a theme tune then for Narcos Mexico.

Tennessee Blues by Bobby Charles

Coping with isolation during the first lockdown I cycled relentlessly, heading out of London to Kent or Essex or through a labyrinth of south-east London streets, travelling when no travel abroad was possible. When the second lockdown was announced I cycled the short distance to Rat Records in Camberwell, south-east London, desiring fresh sounds to get me through the next month: finding Bobby Charles’ eponymous 1972 LP made my heart skip a beat. A Cajun singer and songwriter, Charles is so laidback he sounds like he’s singing in his hammock. Very soulful, extremely swampy, featuring the most exquisite accordion, Tennessee Blues is languid and lovely. Listening to Bobby’s honeyed voice transports me to Whiskey River, a dancehall in rural Louisiana near Lafayette that faces on to a bayou. Cajun and zydeco bands play every Sunday, everyone dances the two-step and the alligators boogie in the bayou.

Right On by OMC

While I’ve lived in London for decades, New Zealand remains “home” in many ways. Unable to be there while my father faded, I listened to lots of music from Aotearoa (the Māori name for New Zealand), this tune especially. OMC stands for Otara Millionaires’ Club led by Pauly Fuemana, a Niuean-Māori youth who grew up in the hardscrabble South Auckland suburb of Otara and saw his dreams come true when he scored internationally with How Bizarre in 1996. Right On is mestizo Polynesian soul – bright harmonies, mariachi trumpet, furious strumming, supersonic Hawaiian steel guitar and Pauly speak-singing in the broadest Kiwi accent – reminding me what I love most about my South Pacific homeland. Reader, I managed to return, so escaped lockdown 3 and spent Christmas with my mum!

Garth Cartwright is the author of Going For A Song: A Chronicle Of The UK Record Shop (The Flood Gallery) and the forthcoming London’s Record Shops (The History Press)