California ROUNDUP

Despite one of the lowest rates of infection and death of any major city in the country, San Francisco public schools have been closed for in-person learning since March. On Wednesday, city officials announced an unusual move: legal action against its own Board of Education to push the district to reopen schools more quickly.

“There’s nothing like a lawsuit to focus the mind and force things to come to a head,” Dennis Herrera, the city attorney, said in an interview Wednesday.

Mr. Herrera said he would seek an injunction to mandate the Board of Education, which operates independently from city hall, to produce a plan for reopening.

San Francisco has one of the highest rates of private school enrollment in the country, a distinction that during the pandemic has created a kind of de facto segregation.

Around 15,000 students in private schools are attending in person classes in the city while 54,000 public school students are studying online, widening the gap in the city between those with means and those without.

Mr. Herrera said data from across the San Francisco Bay Area showed that there has been very little in-school transmission of the virus in places where schools are in session.

Across the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County, 90 percent of schools have resumed in-person instruction and there have been nine reported cases of in-school transmission. In San Francisco, there have been five reported cases in the private schools, many of which have been opened since the beginning of the school year.

“If you look at the scientific consensus it’s that schools can reopen safely — for teachers, staff and students — with proper precautions,” Mr. Herrera said.

Mr. Herrera’s statement was consistent with C.D.C. guidance issued last week that said the “preponderance of available evidence” indicated that in-person instruction could be carried out safely as long as mask-wearing and social distancing were maintained. But the guidance said that local officials also must be willing to impose limits on other settings — like indoor dining, bars or poorly ventilated gyms — to keep infection rates low in the community at large.

Many parents of public school children in San Francisco were particularly angered by the Board of Education’s decision last week to rename the empty schools. The Board voted to delete George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, among many other historical figures and prominent San Franciscans — anyone the Board judged to have held slaves, oppressed women or “diminished the opportunities of those among us to the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The reopening of schools was not discussed at the renaming meeting, which went late into the night. Mayor London Breed, among others, lashed out at the board.

“Let’s bring the same urgency and focus on getting our kids back in the classroom, and then we can have that longer conversation about the future of school names,” Ms. Breed said.

In other California news:

-

The Biden administration announced on Wednesday two federally backed community vaccination centers in two particularly vulnerable, hard-hit areas: East Oakland and Los Angeles. California State University, Los Angeles and the Oakland Coliseum would host the sites, Jeffrey D. Zients, the White House’s Covid-19 response coordinator, said at a news conference. Each center would be primarily staffed by federal workers, which include the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Departments of Agriculture, Defense and Health and Human Services, he said.

An international program to supply Covid-19 vaccines at low or no cost to countries around the world plans to deliver more than 300 million doses by June 30, it said on Wednesday.

But even with that help, many of the world’s poorest countries are likely to lag far behind in vaccinating their citizens, and may not be able to mount any large-scale effort this year.

Scientists say that could leave the entire world, even people in widely vaccinated countries, more vulnerable, at a time when worrisome new variants of the virus are cropping up and spreading worldwide.

The assistance program, known as Covax, was set up by international organizations to try to counteract “vaccine nationalism” and ensure that the scramble for vaccines among rich countries did not leave poorer nations out in the cold.

Covax said on Wednesday that it hoped to ship 336 million doses of the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine to 145 countries in the first half of the year, with shipments to begin late this month or early in March. The vaccine deliveries would be among the first to reach low- and middle-income countries.

Some 96 million of the doses would come directly from AstraZeneca, Covax said, and the rest from the Serum Institute of India. The program said that close to 100 million doses of the total would be delivered by the end of March.

Covax cautioned that its figures and delivery dates were “indicative” estimates, based on what manufacturers had said would be available. Production hiccups and other problems could result in lower deliveries.

In addition to the AstraZeneca doses, Covax plans to supply a much smaller number, around 1.2 million, of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine in the first quarter of the year, according to Seth Berkley, chief executive of the GAVI Alliance, the organization that leads the Covax program.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine requires storage at extremely cold temperatures, so those shipments will go to just 18 countries, selected for their ability to meet those requirements. By the end of the year, Covax expects to ship 40 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

Along with the GAVI Alliance, the partners in the Covax program include the World Health Organization, Unicef and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. Covax has raised pledges of $6 billion, including $4 billion from the United States, with a goal of supplying up to 2 billion doses to low- and middle-income nations by the end of 2021.

The executive director of Unicef, Henrietta Fore, said on Wednesday that Unicef had reached a long-term agreement on Covax’s behalf with the Serum Institute of India for up to 1.1 billion doses of the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine and one developed by Novavax. The agreement, which extends beyond 2021, would supply vaccine to around 100 low-and middle-income countries for about $3 a dose.

“This is a great value for Covax donors,” she said, showing how the program “can negotiate in bulk for the best possible deals.”

transcript

transcript

New Jersey Eases Indoor Coronavirus Restrictions

Gov. Philip D. Murphy said New Jersey would lift its statewide 10 p.m. indoor dining curfew and raise capacity limits on a number of indoor businesses, including restaurants, from 25 percent to 35 percent.

-

Today, I will be signing an executive order that will carefully and responsibly increase indoor capacities at a number of our businesses and venues from 25 percent to 35 percent. And this order will take effect at 8 a.m. this Friday, Feb. 5. I feel confident in signing this order because of the recent trends in our hospitals and our rate of transmission. So first, as of Friday, all restaurants will be able to expand indoor dining to 35 percent of their listed capacity. That’s up from 25 percent. The statewide requirement that all restaurants end indoor service as of 10 p.m. will be lifted. However, and this is important, municipalities or counties may continue to regulate the hours of operation of in-person restaurant service. after 8 p.m. The prohibition on seating at indoor bar areas will remain in effect as it creates a danger of close and prolonged proximity between and among patrons, bartenders and servers. Additionally, indoor entertainment and recreation areas, including casinos and gyms, may also accommodate 35 percent of their capacities, as may all personal care businesses such as barbershops and salons. And finally, the order will allow indoor gatherings that are religious ceremonies or services, wedding ceremonies, political activities and memorial services or funerals to be similarly at 35 percent of capacity, but no more than 150 total individuals. Performance venues may also expand to 35 percent of listed capacity, but no greater than 150 individuals.

New Jersey is relaxing its rules related to indoor dining and drinking, just in time for Super Bowl LV on Sunday.

A 10 p.m. curfew for indoor dining will be lifted starting on Friday, two days before the big game between the Kansas City Chiefs and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

Gov. Philip D. Murphy also raised the ceiling on indoor dining to 35 percent of capacity, up from 25 percent — the first change to the state’s pandemic restrictions since indoor dining resumed in New Jersey over Labor Day weekend. The higher limits also apply to other indoor venues like gyms and casinos.

New Jersey was one of the last states to resume indoor dining. Struggling restaurant and bar owners lobbied the governor for months to expand capacity limits. Super Bowl Sunday is typically one of the busiest days of the year for bar and restaurant owners.

“We believe we can make this expansion without adding further stress on our health care system,” Governor Murphy, a Democrat, said in his announcement.

Mr. Murphy imposed the 10 p.m. indoor dining curfew in November when virus cases in the state were rising sharply. He also ordered owners to eliminate all bar seating, a rule that is not being relaxed now. (Many establishments responded by placing two-person cafe tables next to their bars.)

At that time, New Jersey was reporting an average of 2,605 new virus cases a day. On Wednesday, the average stood at 4,548 a day, according to a New York Times database.

In neighboring New York State, Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced last Friday that indoor dining would be allowed in New York City starting on Feb. 14 — Valentine’s Day — at 25 percent of capacity.

As recently as December, the vaccine maker Novavax appeared to once again be on the brink of failure. Manufacturing troubles had forced the little-known Maryland company, which in its 34-year history had never brought a vaccine to market, to delay the U.S. clinical trial of its experimental Covid-19 inoculation, jeopardizing its $1.6 billion contract with the federal government. And two Covid-19 vaccines made by its competitors were already shipping around the country, leaving some to wonder whether Novavax would ever catch up.

But the picture has significantly improved. The company announced last week that its vaccine showed robust protection in a large British trial and also worked, although not nearly as well, in a smaller study in South Africa against a contagious new variant.

And the scarcity of the two vaccines authorized in the United States, made by Moderna and Pfizer, seems to have made it easier for Novavax to recruit volunteers in its trial here. That speedy enrollment has put the company on track to have results this spring, with possible government authorization as early as April. If all goes right — and nothing is guaranteed — that would mean an influx of 110 million vaccine doses, enough for 55 million Americans at two doses each, by the end of June.

The potential success of Novavax’s candidate carries global implications. Unlike Pfizer’s and Moderna’s shots, the Novavax vaccine can be stored and shipped at normal refrigeration temperatures. The company is setting up plants around the world to produce up to 2 billion doses per year

With contagious variants circling the globe, more vaccines are desperately needed.

Novavax has signed up more than 20,000 people so far in its late-stage trial in the United States and Mexico, two-thirds of its goal of 30,000 participants. If it keeps enrolling volunteers at the same pace, it will complete recruitment more quickly than the Pfizer and Moderna trials did last year.

If Novavax is successful, the new vaccine could add to a widening portfolio of shots in the United States by late spring. Moderna and Pfizer have deals with the United States to supply 400 million doses, enough to fully vaccinate 200 million people, by the middle of the year, and both companies are in talks to supply an additional 100 million doses each after that.

Johnson & Johnson, which recently reported that its one-dose vaccine was effective in a large U.S. trial, could receive authorization this month, but may not be able to supply the United States in significant numbers until April. AstraZeneca’s U.S. trial is also underway, and that company has a deal to supply Americans with 300 million doses of its two-shot vaccine.

But any number of obstacles could trip up Novavax’s progress. As other vaccines become more widely available, participants in Novavax’s trial could drop out of the trial. Even though its results in Britain were promising, the U.S. study could yield different results. Or the company could fail to prove to regulators that it can reliably manufacture its vaccine on a large scale. Given the likelihood that the United States may soon have three authorized vaccines available to the public, the company is under pressure to move quickly, or risk losing ground to competitors.

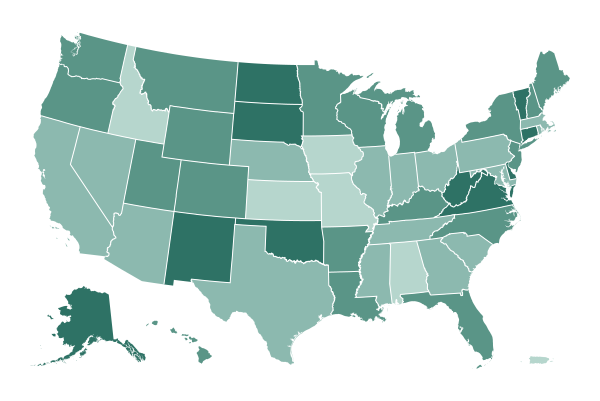

Almost half of U.S. states have begun allowing teachers to be vaccinated as officials decide which groups should be given priority for early protection against the coronavirus, a New York Times survey shows. By this week, 24 states and Washington, D.C., were providing shots to teachers of kindergarten through high school students.

How quickly states give shots to teachers from a growing-but-still-limited vaccine supply has become a central point in the debate about how best to reopen school systems, at a time when more contagious virus variants are emerging and spreading.

In some states where many teachers are already teaching in-person classes, teachers are not yet eligible for vaccines. And for many places where classes are mainly remote, vaccinating teachers has been a first step to returning children to classrooms, though it is not the only factor.

“This discussion is not about if we return, but how we return,” Stacy Davis Gates, a leader of the Chicago Teachers Union said recently amid a standoff in that city over whether students in elementary and middle schools — and their teachers — should return to classrooms immediately. Ms. Davis Gates said, “How we return is with the maximum amount of safety that we can obtain in an agreement.”

Who is currently eligible for the vaccine in each state

All states are vaccinating health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities, and many states have expanded eligibility to other priority groups. Click on a state for more information.

*Eligible only in some counties. Data as recent as Feb. 2.

Sources: State and county health departments.

On Wednesday, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said that although teachers should be prioritized for vaccination as essential workers, “vaccination of teachers is not a prerequisite for safe reopening of schools.” Her statement was in line with recent research suggesting that measures, such as masking and social distancing, can effectively mitigate the spread of the coronavirus in schools, especially where community virus levels are controlled.

Last week, the C.D.C. weighed in with a striking message: Children should return to classrooms because it’s safe for them to do so.

The agency said the “preponderance of available evidence” indicated that in-person instruction could be carried out safely as long as mask-wearing and social distancing were maintained. Its researchers found “little evidence that schools have contributed meaningfully to increased community transmission” when proper safety precautions were followed.

There was an important caveat: Local officials also must be willing to impose limits on other settings — like indoor dining, bars or poorly ventilated gyms — to keep infection rates low in the community at large.

The debate remains far from settled, and teachers’ unions across the country have pressed for teachers to be given high priority for receiving a vaccine.

Oregon began vaccinating K-12 teachers last month, giving them an earlier place in line than some residents who are 75 years or older, who are only eligible for shots in certain counties. Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, said the move was part of her plan to bring students back into the classroom during this school year.

“For every teacher who is back in the classroom, they help 20, 30, 35 students get their lives back on track,” Ms. Brown said. “They help ensure 20, 30, 35 kids have access to mental health support. They make sure 20, 30, 35 kids get breakfast and lunch several days a week. And they allow families to know their children are in good hands when they go to work.”

As part of Gov. Mike DeWine’s goal to bring students back to in-person learning either full- or part-time by March 1, Ohio began vaccinating teachers in certain counties this week. Union officials have praised that decision, but say it is not the sole answer to getting students back to school safely. Children will not yet have shots, they note, nor will all adults in schools.

“Even when educators are able to be vaccinated, it will remain critically important to continue following all C.D.C. guidance to keep our schools safe and open for in-person instruction when possible,” Scott DiMauro, president of the Ohio Education Association, said in a news release.

An earlier version of this article misstated the first name of the president of the Ohio Education Association. He is Scott DiMauro, not Steve.

A team of experts from the World Health Organization investigating the origins of the pandemic visited a research center in Wuhan, China, on Wednesday that has been a focus of several unfounded theories about the coronavirus.

The W.H.O. scientists met with staff members at the center, the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which houses a state-of-the-art laboratory known for its research on coronaviruses.

The institute came under scrutiny last year as the Trump administration promoted the unsubstantiated theory that the virus might have leaked from a government-run laboratory in China. But many senior American officials have said in private that evidence pointing to a lab accident is mainly circumstantial.

Most scientists agree that the coronavirus most likely emerged in the natural world and spread from animals to humans. Peter Daszak, one of the experts on the W.H.O. team, described the conversation on Wednesday at the Wuhan institute as candid. “Key questions asked & answered,” he wrote on Twitter, without providing details.

One of the people the W.H.O. team met was Shi Zhengli, known as China’s “Bat Woman” for her study on coronaviruses found in bats. In June, Dr. Shi had expressed initial fears that the virus could have leaked from the lab, according to an interview with the Scientific American. Later, checks showed that none of the gene sequences had matched the viruses that staff members were studying.

Separately, China announced on Wednesday that it would provide 10 million Covid-19 vaccines to Covax, a global body established to promote equitable access to coronavirus inoculations.

The decision is “another important measure taken by China to promote the fair distribution of vaccines,” said Wang Wenbin, a Foreign Ministry spokesman.

He also said that the World Health Organization had started reviewing the emergency authorization of vaccines. It was unclear which vaccines Mr. Wang was referring to. Two vaccines — manufactured by the Chinese companies Sinovac and Sinopharm — have been approved for use in China.

Whether the threshold is 65 or 80, people who meet their state’s age requirement are eligible to get a Covid-19 vaccination shot in every U.S. state but one.

The exception: Rhode Island, the only state still in the first phase of its vaccination campaign, which restricts access to health care workers and residents of long-term care facilities.

If Barbara Diener, 65, had known she still wouldn’t be eligible for the vaccine in Rhode Island — where she and her husband moved to be closer to family — she said they might not have moved there in November from Georgia, where anyone 65 or older can get a shot.

“We moved here three months ago from Georgia, where everyone I know has been vaccinated,” said Ms. Diener, a travel agent. “We’re a little disappointed that the state of Rhode Island, being as small as it is, just can’t get it together.”

The state health director, Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, said last week that Rhode Island was expanding eligibility slowly because the state wanted to make sure that the people most at risk were vaccinated first.

“In addition to how many people you vaccinate, who you vaccinate matters,” Dr. Alexander-Scott said. “And that’s what distinguishes Rhode Island, and how we are taking this thoughtful approach.”

Where older adults are eligible for vaccines

Most states have started vaccinating older adults, though the minimum eligibility age varies widely.

Not yet prioritizing by age

*Eligible only in some counties. Data as recent as Feb. 2.

Sources: State and county health departments.

Ms. Diener and her husband both came down with Covid-19 last March, and her husband was hospitalized for two weeks. They want to get inoculated as soon as they can. But since neighboring states are limiting vaccinations to their own residents, they have little choice but to wait.

“My doctor is in Massachusetts, because we’re so close in proximity, but I can’t get it in Massachusetts either,” Ms. Diener said.

Rhode Island’s health department said last week that it was starting to vaccinate a small number of especially vulnerable people 75 and older — people who are part of a registry indicating that they need extra assistance during an emergency. In about two weeks, the department plans to start making doses available to everyone in that age group.

State residents ages 65 to 74 are forecast to become eligible at the end of the month, according to the health department’s projections.

Dr. Alexander-Scott said the state was being strategic because of its “very limited supply” of vaccine.

The state has administered about 54 percent of its available vaccine doses so far, and has given at least one of the two required shots to 6.5 percent of its population, a lower proportion than most other states.

The New York City health commissioner, Dr. Dave A. Chokshi, said on Wednesday that he tested positive for the coronavirus.

“I recently got tested and received a positive diagnosis for Covid-19,” Dr. Chokshi said in a statement. “I now have mild symptoms, but they are manageable.”

Dr. Chokshi, who took the post in August, has been central to the city’s efforts to contain the virus, as cases and hospitalizations rose in recent months.

He has sat by Mayor Bill de Blasio in news conferences, warning residents of the continued threat of infection, and recorded public service announcements urging adherence to social distancing guidelines.

Mr. de Blasio said on Wednesday that he had not seen Dr. Chokshi in person “for a while.” The city’s contact tracing program was working to identify others, including city employees, who may have been in contact with the commissioner.

Dr. Chokshi, who helps oversee the city’s vaccination campaign, had recently been volunteering at vaccine clinics and giving people inoculations, said Dr. Jay Varma, the mayor’s senior adviser for public health. But the commissioner had not yet been vaccinated himself, Dr. Varma said, out of concern that he might be seen as cutting the line.

Mr. de Blasio said Dr. Chokshi did not yet fall into one of the eligible categories.

“We have to show people there will be fairness here in this city,” the mayor said.

Mr. de Blasio said that the city would begin to allow vaccinations for restaurant workers, drivers of taxis and for-hire vehicles, and workers and residents at facilities for people with developmental disabilities.

Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York widened the state’s eligibility requirements to include those groups on Tuesday after the federal government said it would increase the supply of vaccine doses available to state and local governments.

On Wednesday afternoon, the two leaders also announced that a vaccination site would open at Yankee Stadium on Friday to serve residents of the Bronx, which includes some of the city neighborhoods hit hardest by the pandemic. Fifteen thousand appointments will be made in the site’s first week of operation, and proof of Bronx residence will be required.

On average, 8.09 percent of coronavirus tests in the city have been coming back positive over the last week, the mayor said. It was a slight decline from previous weeks, but higher than the rate in December, when indoor dining was not allowed.

Across the state, on average, 4.86 percent of virus tests in the city have been coming back positive over the last week, the governor’s office said Wednesday. The state has so far administered 92 percent of first doses of the vaccine that it has received from the federal government, the office said.

Hundreds of businesses in Poland, including gyms, bars and restaurants, are in revolt against the government and risking hefty fines by reopening despite the country’s coronavirus restrictions.

What started last month with an online initiative called #OtwieraMY, meaning #WeAreOpening, has increasingly been taken up as a call to action by beleaguered business owners.

The movement has produced maps pinpointing the hundreds of restaurants, hotels, cafes and even ski slopes that claim to be open despite measures which require them to remain shut.

The Polish government on Monday allowed museums, art galleries and stores to start welcoming customers again. But sports facilities, hotels, bars and restaurants were told they must remain closed until at least mid-February.

A pub in the capital city — known for its walls decorated with beer caps — appeared to joke on Facebook that it would rebrand as the “Warsaw Beer Cap Museum” so it could reopen. The Polish Fitness Federation, which has been vocal in its calls to end the lockdown, told one local news outlet that almost 1,600 sports facilities had reopened at the start of February in defiance of the ban.

Businesses can face fines of up to $8,000 for violating the measures, but that has not deterred anti-lockdown activists who say their approach has been backed by the courts.

In January, a justification was issued for a decision at a court in southern Poland that had overturned a fine imposed on a hairdresser last year. In that case, the court ruled that there was no constitutional basis for prohibiting conducting business activities, and several other courts have since made similar rulings.

The head of the Polish Fitness Federation, Tomasz Napiorkowski, told the news outlet Notes from Poland that dozens of gyms had been subject to inspections by officials and that no fines had been handed out. But, he said, the federation would not release a list of reopened clubs so as to “not make work easier” for the authorities.

In New York City, despite its many major hospitals and research institutions, only about 55 coronavirus cases a day on average last month were sequenced and screened for more contagious variants.

That amounted to just 1 percent of the city’s new cases, a rate far below the 10 percent that some experts say is needed to understand the dynamics of the pandemic in New York at a time when variants that may blunt the effectiveness of existing vaccines have led to surging cases in Britain, Brazil and South Africa.

By the end of February, New York City health officials hope to have a more robust surveillance program in place that would involve sequencing the genomes — that is, examining the genetic material for mutations — of about 10 percent of new virus cases, according to Dr. Jay Varma, a senior public health adviser to City Hall.

With an average of more than 5,000 new cases a day in recent weeks, that would provide a good picture of which variants are present in New York and how widely they are proliferating, Dr. Varma said.

But the effort to reach that benchmark is underscoring how, a year into the pandemic, local, state and federal officials have often been slow to mobilize resources for public health needs.

“Trying to get laboratories that are primarily focused on things like human genome sequencing specifically for cancer or other conditions to shift their interest to work on pathogens sometimes takes effort,” he said.

The capacity to sequence the genomes of as many virus samples as necessary already exists, scattered across the city, though it has been largely untapped.

“Every institution is doing their own thing,” Professor Adriana Heguy of New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, whose team has been sequencing some 96 samples a week and whose research last year helped establish that New York’s pandemic arrived via Europe, not China.

With its major academic medical centers and research institutions, there are far more sequencing machines in New York than would be needed to check the coronavirus genomes from every positive case, were anybody inclined to do so.

“Our machines could handle thousands or hundreds of thousands,” said Dr. Neville Sanjana, a scientist with a lab at the New York Genome Center in Lower Manhattan. “So the capacity is just not the issue.”

The issue for research laboratories — strangely enough, amid a pandemic that has probably infected more than a quarter of New Yorkers — is access to samples. In New York, there is no high-volume pipeline of positive virus samples from hospitals or testing sites to research laboratories to conduct genetic surveillance.

Across the United States, some doctors are seeing reimbursement rates so low that they do not cover the cost of the test supplies, jeopardizing access to a tool experts see as crucial to stopping the virus’s spread.

With new variants of the coronavirus emerging, experts say testing will be crucial to containing the pandemic’s spread. But the low fees have led some doctors to stop testing certain patients, or forgo testing altogether.

The problem of low reimbursement rates appears to be most common with pediatricians using in-office rapid testing.

“We are not doing Covid testing because we cannot afford to take the financial hit in the middle of the pandemic,” said Dr. Suzanne Berman, a pediatrician in Crossville, Tenn. Her clinic serves a low-income Appalachian community where the coronavirus is spreading rapidly, and 17 percent of tests are coming back positive as of this week.

Rapid in-office tests are less sensitive than those sent off to a lab, which means they miss some positive cases. Researchers are still learning about the efficacy of these tests in children. Still, infectious disease experts say that fast turnaround tests are important in controlling the pandemic, particularly in areas where other types of testing are less available.

Across the United States, multiple doctors identified UnitedHealthcare and certain state Medicaid plans as the ones that routinely pay test rates that do not cover the cost of supplies.

Medicaid and Medicare often pay lower prices than private insurers do. But the reimbursements from a large private insurer like UnitedHealthcare came as a shock to doctors.

A spokesman, Matthew Wiggin, said that UnitedHealthcare was not underpaying for coronavirus testing, and that its rates were consistent with those of other health plans.

“We want to make sure every member has access to testing and encourage any provider with payment questions to contact us so we can resolve their concerns,” he said in a statement.

Doctors who have complained to UnitedHealthcare and other health plans, however, say they’ve been offered little recourse. One was told it wasn’t an issue that any other doctor had raised. Another was directed to find a supplier with a lower price.

McClurg, in Missouri’s rural Ozarks, is more a crossroads than a town, and it’s home to a particular strain of old-time dance music that is not played in precisely the same way anywhere else.

Pre-pandemic, in an abandoned general store, Alvie Dooms, 90, and Gordon McCann, 89, would play rhythm guitar. Nearly a dozen more musicians would join in on fiddle, mandolin, banjo and upright bass. Their tunes had names like “Last Train Home,” “Pig Ankle Rag” and “Arkansas Traveler.”

The McClurg jam, as the Monday night music and potluck fest was known, endured for decades, the last gathering of its kind in the rural Ozarks. But the coronavirus pandemic has silenced the instruments, at least temporarily. And the suspension has led to worry: What will become of this singular musical tradition?

“Because it’s ear music, it’s a little bit fragile,” said Howard Marshall, 76, a retired professor at the University of Missouri and a fiddler himself. “I’m not playing it exactly like the next chap will play it.”

“I’m one of the younger ones, and I’m 74,” said Steve Assenmacher, a bass player who lives just up the hill from the McClurg Store and acts as its caretaker.

When the pandemic led Missouri officials to limit in-person gatherings last spring, the musicians pledged to find a way to keep the sessions going. Last May, they moved to a barn adjacent to the store and seated visitors at the entrance, in the open air.

The jams continued for most of the year. But in mid-November, as alarmed hospital officials warned that their facilities were nearing capacity and the frigid temperatures became unpleasant, the jam session was called off indefinitely.

Dr. Marshall said the internet had guaranteed that many of the songs would endure. It’s the stories behind the songs and institutional knowledge that will disappear if jams like McClurg cease to exist.

Even if the musicians aren’t stricken with Covid-19, he said, an extended pause is precious time — because they can “get rickety” with age.

And that’s exactly what is happening with the McClurg elders.

Mr. McCann suffered a second stroke in November.

And Mr. Dooms, who has already survived three major heart attacks, said that his “lungs ain’t no good.”

Once the winter has passed, Mr. Assenmacher hopes to welcome musicians back to the open-air barn. But, he said, until the musicians have been vaccinated and public health officials declare widespread immunity, the old general store in McClurg will remain closed.

global roundup

Iran announced on Tuesday that its first batch of Covid-19 vaccine, Russia’s Sputnik V, would arrive on Thursday. It coincided with a study published on Tuesday in The Lancet, a British medical journal, that the vaccine was safe and effective.

The news could not come at a better time for Iran. Vaccines, like everything else in the Islamic Republic, have been politicized and subject to disinformation from the top down.

Iran’s supreme leader has declared a ban on importing American- and British-made vaccines, saying they could not be trusted. The Iranian Health Ministry canceled a batch of donated Pfizer doses and said it would import vaccines from Russia and China and develop a vaccine with Cuba.

For weeks, senior Iranian health officials have publicly argued over whether it was safe to inoculate Iranians with the Russian vaccine because it had not been approved by the World Health Organization or any Western medical agency.

Before the Lancet study said that Sputnik V had a 91.6 percent efficacy rate against the coronavirus, several high-profile Iranians had expressed skepticism about it, including Iran’s top infectious disease official and the head of Parliament’s health committee. And 98 physicians from Iran’s largest union of medical workers wrote a letter last week to President Hassan Rouhani urging him not to purchase the “unapproved and unsafe” Sputnik vaccine.

Other health officials pushed back, defending the Russian vaccine, including the health minister and his former spokesman.

On Twitter, a hashtag trending in Persian was #buysafevaccines, as many Iranians declared that they would reject Russian- and Chinese-made vaccines.

In other news from around the world:

-

New Zealand’s drug regulator said on Wednesday that it had provisionally approved the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine but added 58 conditions, most of which require the manufacturer to supply extra data. Pfizer said last week that the first of the 1.5 million vaccines on order were expected to arrive before the end of February. New Zealand’s director-general of health, Ashley Bloomfield, has said that the country will be “ready to start vaccinating people as soon as a vaccine arrives.”

-

The state of Victoria, Australia, which includes the city of Melbourne, declared the coronavirus “technically eliminated” on Wednesday — for the second time — after a month in which no new cases were recorded. The state government also announced a rollout plan for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine that is scheduled to begin in late February. Frontline health workers will be among those included in the first phase, and nine vaccination hubs will be established at the state’s major hospitals. “This is a significant day in the response of the Victorian community to the pandemic,” said Martin Foley, the state’s health minister. “It turns a corner.”

-

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of Canada said on Tuesday that his government had signed a tentative deal with Novavax to produce the company’s coronavirus vaccine at a government facility in Montreal, once the drug and the site are approved by domestic regulators. Canada has a separate agreement to purchase 52 million doses of the Maryland-based company’s drug, but its regulators have so far only approved the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines. Novavax is expected to deliver results from its Phase 3 clinical trials in the United States in March, and to deliver 100 million doses for use there later this year.

A military judge on Tuesday indefinitely postponed the arraignment of three prisoners at Guantánamo Bay who were scheduled to make their first court appearance in 17 years of detention, finding that the coronavirus pandemic made it too risky to travel to the Navy base.

The Indonesian prisoner known as Hambali, who has been held since 2003 as a former leader of a Southeast Asian extremist group, and two people accused of being his accomplices were scheduled to appear at the war court on Feb. 22. But Col. Charles L. Pritchard Jr., the military judge who was to travel to Guantánamo this week, ruled that “the various counsels’ belief that their health is at significant risk by traveling” to the base in Cuba was reasonable.

Colonel Pritchard is the most recent military judge to join the Guantánamo military commissions bench, and the latest to postpone a proceeding as too risky in nearly a year of cancellations because of the coronavirus. Pretrial hearings in the death-penalty case against five men accused of plotting the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks have been delayed for a year.

The judge, court staff and lawyers bound for the hearing began a quarantine in the Washington area over the weekend before a charter flight to the base on Thursday.

Once there, the passengers were to be individually quarantined for 14 days under a plan devised by prosecutors to protect those living on the base of 6,000 residents and at the prison from the threat of infection.

The case had been dormant throughout the Trump administration, but on the second day of the Biden administration, a senior Pentagon official appointed under the Trump administration who had been put in charge of the military commissions approved the prosecutions.

The defendants include Mr. Hambali, who is charged as Encep Nurjaman and accused of being the former leader of the extremist group Jemaah Islamiyah, and those accused of being his accomplices, Mohammed Nazir Bin Lep and Mohammed Farik Bin Amin, who are Malaysian.

The three men were captured in Thailand in 2003 and are charged with conspiring in the 2002 nightclub bombings in Bali, which killed 202 people, and the 2003 Marriott Hotel bombing in Jakarta, which killed at least 11 people and wounded at least 80. They spent their first three years in the C.I.A.’s secret prisoner network before they were transferred to Guantánamo for trial in 2006.

transcript

transcript

Boris Johnson Pays Tribute to ‘Captain Tom’

Prime Minister Boris Johnson of Britain urged the nation to clap in memory of “Captain Tom,” a 100-year-old Army veteran who raised millions for Britain’s health workers.

-

Capt. Sir Tom Moore, Captain Tom as we all came to know him, dedicated his life to serving his country and others. His was a long life, lived well, whether during his time defending our nation as an army officer and last year, bringing the country together through his incredible fund-raising drive for the N.H.S. that gave millions a chance to thank the extraordinary men and women of our N.H.S. who protected us in this pandemic. As Captain Tom repeatedly reminded us, please remember, tomorrow will be a good day. He inspired the very best in us all, and his legacy will continue to do so for generations to come. Mr. Speaker, we now all have the opportunity to show our appreciation for him, and all that he stood for and believed in. That’s why I encourage everyone to join in a national clap for Captain Tom, and all those health workers for whom he raised money at 6 p.m. this evening.

When the coronavirus was just beginning to take its toll across Europe, Thursday nights became a national moment of reflection and catharsis in Britain, as people across the country stood on front steps or reached out their windows to clap or bang pots in honor of the doctors and nurses of the National Health Service and the essential workers on the front lines.

The nation clapped again on Wednesday, this time for Tom Moore, a 100-year-old Army veteran who became a national hero for his fund-raising efforts early in the pandemic. He tested positive for Covid-19 in January and died on Tuesday.

Neighborhoods united with noise in the February cold, though without always achieving the decibel level heard in the 10 weeks of communal claps in the spring.

Mr. Moore’s death came at a particularly trying time, with Britain again under stay-at-home orders nearly 11 months after the first round of widespread restrictions were imposed, and the coronavirus still ravaging the nation. Lawmakers held a moment of silence in Parliament on Wednesday in memory of Mr. Moore and all those who have died during the pandemic — more than 108,000 as of Wednesday morning.

“Tonight, let’s clap for the spirit of optimism that he stood for, but let’s also clap for all those he campaigned for,” Prime Minister Boris Johnson said at a news conference later in the day, referring to the country’s health care workers. “Let’s do everything we can to carry on supporting them.”

Mr. Moore rose to prominence by walking laps around his patio, steadied by a walker, to raise money for the health service, including 100 laps before turning 100 last April. When images of his walks went viral online, pledges poured in, and he wound up raising 32.8 million pounds, or $45 million.

More than that, he became a symbol of resilience and hope, a bright spot in a nation besieged by the pandemic. The British media nicknamed him Captain Tom, for the rank he held when he retired from the military. He was made an honorary colonel by the Army Foundation College last summer, and Queen Elizabeth II knighted him.

England’s chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, said on Wednesday evening that the country had passed the peak of its second wave of coronavirus infection, a wave that has proved much larger and more deadly than the first. But while reports of new cases have begun to decline, he cautioned, the daily death toll is likely to remain high “for quite some time.”

The vaccine developed by the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca has the potential to slow the transmission of the virus, according to a new paper.

The paper by researchers at the University of Oxford is the latest to report evidence suggesting that a coronavirus vaccine may be able to reduce transmission of the virus, though scientists have emphasized that the data are preliminary and the degree of protection unknown.

The researchers measured the impact on transmission by swabbing participants every week seeking to detect signs of the virus. If there is no virus present, even if someone is infected, it cannot be spread. And they found a 67 percent reduction in positive swabs among those vaccinated.

The paper, which has not been peer-reviewed, looked at data from clinical trials in Britain, Brazil and South Africa, the results of which were first reported late last year.

Matt Hancock, the British health secretary, hailed the results on Wednesday as “absolutely superb.”

“We now know that the Oxford vaccine also reduces transmission and that will help us all get out of this pandemic,” Mr. Hancock said in an interview Wednesday morning with the BBC.

The results, he said, “should give everyone confidence that this jab works not only to keep you safe but to keep you from passing on the virus to others.”

Some scientists looking at the limited information released cautioned that more analysis of the data was needed before such broad conclusions could be firmly stated.

“While this would be extremely welcome news, we do need more data before this can be confirmed and so it’s important that we all still continue to follow social distancing guidance after we have been vaccinated,” said Dr. Doug Brown, chief executive of the British Society for Immunology.

The Oxford and AstraZeneca researchers also found that a single dose of the vaccine was 76 percent effective at preventing Covid-19. The data measured the three months after the first shot was given, not including an initial three-week period needed for protection to take effect.

The encouraging results, lend support to the strategy deployed by Britain and other countries to prioritize providing as many first doses of vaccines as possible, setting aside concerns that people will get their second doses later than initially planned.

The latest data do not have bearing on the debate over whether to further space out the doses of the two vaccines authorized in the United States, those from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, since the data on AstraZeneca’s candidate cannot be generalized to other vaccines.

Some scientists have called on the United States to follow the lead of Britain and other countries that have opted to delay the second doses of vaccines by up to 12 weeks. But U.S. federal officials have resisted, saying such a move would not be supported by the data from clinical trials of the two vaccines currently available across the nation. Tuesday’s results could amplify pressure on U.S. health officials to delay second doses of AstraZeneca’s vaccine, though it has not yet been authorized by the country.

The vaccine appeared more effective when the interval between the two shots was longer than the originally intended four-week gap, the Oxford and AstraZeneca researchers found. Among clinical trial participants who got two standard-strength doses at least three months apart, the vaccine was 82 percent effective, compared to 55 percent effective when the doses were given less than six weeks apart.

A vaccination strategy that spaces out doses by three months “may be the optimal for rollout of a pandemic vaccine when supplies are limited in the short term,” the researchers wrote.

The newly released paper builds on data issued late last year, which found that the vaccine was 62 percent effective when given as two standard-strength doses. In those initial findings, the vaccine’s efficacy was much higher, at 90 percent, when the first dose of the vaccine was given at half-strength.

Oxford and AstraZeneca researchers initially attributed the different levels of effectiveness to the lower strength of the initial dose. But they gradually reached a different conclusion: the amount of time between doses was the more likely explanation.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration is waiting on data from a clinical trial that enrolled about 30,000 participants, mostly Americans. Results from that study are expected later this month.

The study is expected to arm AstraZeneca with enough safety data to allow it by around early March to seek authorization to provide the vaccine for emergency use.

The United States has agreed to buy 300 million doses of AstraZeneca’s vaccine, but neither the company nor the federal government has said when and in what quantities those doses will be available after the vaccine is approved.

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to findings by researchers investigating the AstraZeneca vaccine’s effectiveness on the new coronavirus. The findings show that the drug has the potential to reduce transmission, not that it drastically cuts transmissions, and the paper is not the first to report such a reduction. The error was repeated in a push notification.