Lau Ka-tung struggled to breathe. He’d been locked in a room that smelled of feces, he said, with a man who kept banging his head on the wall. The lights were always on. Toilet water pooled around his feet. He was under observation in a psychiatric center, where he’d been transferred after requesting depression medication in detention.

This was the price that Lau, 25, was paying for having been caught up in the mass anti-government protests that roiled Hong Kong in 2019.

Lau Ka-tung, a 25-year-old social worker, visits clients in various detention centers four times a week.

(Rachel Cheung / For The Times)

Lau, a social worker, said he was not a protester. He had been on the streets with a team of professionals, displaying a social worker license. He’d tried to deescalate conflict by stepping between police and protesters, he said, using his body as a nonviolent shield.

Regardless, in June 2020, Lau was sentenced to a year behind bars for deliberately obstructing a police officer.

Lau spent a week in jail and in the psychiatric center before his release on bail pending appeal. The only thing that kept him calm inside, he said, was counseling his distraught schizophrenic roommate. “You won’t be alone in this room forever,” he told the man, voicing reassurances he needed himself.

More than 10,000 Hong Kongers were arrested in the aftermath of the pro-democracy protests in 2019. Among them were taxi drivers and security guards, construction workers and high school students, high-profile activists such as Joshua Wong, and thousands of everyday citizens who dared to challenge an authoritarian superpower and are now suffering consequences.

While the world grappled with the coronavirus in 2020, many of these protesters have faded into obscurity, languishing in a grueling legal process that lawyers say could stretch on for years and end in sentences of up to 10 years in prison.

According to official figures, just over 2,400 of the 10,200 Hong Kongers arrested by police in connection with the social unrest of 2019 have been prosecuted over charges such as taking part in a riot, unlawful assembly, assaulting or obstructing a police officer, and weapons possession. Roughly 200 of them have been sentenced to prison.

Police arrest anti-government protesters at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on Nov. 18, 2019.

(Laurel Chor / Getty Images)

Some lawyers say the relatively low number of prosecutions and convictions to this point indicates that there was insufficient evidence for many of the arrests. In one rioting case, the only evidence against a number of defendants was that they were dressed in black and fleeing from police.

The Hong Kong government has denied allegations that it uses prosecution as a political tool, insisting that it is only following due process.

“The mere acquittal of a defendant in no way indicates that the defendant should not have been arrested or charged in the first place,” a spokesperson for the Department of Justice said in a statement to The Times, adding that the threshold for conviction is meant to be higher than for prosecution. “This reflects the proper administration of our criminal justice system.”

Some judges who have cleared defendants of protest-related charges have cited insufficient evidence or unreliable police testimony. That offers hope to defendants who still await trial or have appealed their convictions.

Yet the lengthy legal proceedings are taking a mental and financial toll on defendants. The Department of Justice denies that ongoing cases with limited evidence and its repeated appeal of acquittals are politically motivated.

A lawyer who works with arrested protesters said many of his clients were teenagers at the time, still in secondary school and overwhelmed by the trial process.

“Even adults struggle to deal with such serious lawsuits, let alone kids,” said the lawyer, who asked to remain anonymous due to political sensitivity. The trials could drag on until 2024, he estimated.

They came at “no cost” to the police and prosecution, he said, but have already proved devastating to his young clients and their families.

Many have sunk into depression and some out on bail have fled Hong Kong altogether, seeking refugee status in Taiwan, Canada and other locales. Not all have been successful, including a dozen arrested at sea and detained on the mainland when they sought to depart last year.

Police officers arrest a demonstrator calling for Hong Kong’s independence from China on May 10, 2020.

(Isaac Lawrence / Getty Images)

Two minors have since been extradited back to Hong Kong, but the others remain in detention, while mainland Chinese lawyers their families appointed to represent them have had their licenses revoked.

What began in 2019 as protests against an extradition bill that could have sent Hong Kongers to mainland China for trial turned into a mass movement against police brutality and Beijing’s control over Hong Kong. Mass arrests, COVID-19 restrictions and a harsh new national security law have in turn silenced the protests that had brought hundreds of thousands into Hong Kong’s streets every weekend.

These days, protest graffiti has been washed away. New surveillance cameras loom over streets that fall silent in evenings as restaurants shutter at 6 p.m. “Lennon walls,” those colorful post-it collages that once plastered Hong Kong’s tunnels and bridges with messages of hope for democratic change, are no longer anywhere to be seen.

Yet a remnant network of supporters is still trying to demonstrate solidarity. They keep track of protest-related trials via Telegram and Facebook, asking people to attend and document court hearings. Wall-fare, a concern group on prisoners’ rights, has connected protesters in detention with 600 pen pals and delivered over 7,000 letters since January 2020.

A Hong Kong restaurant has volunteered to cater prison food despite operating at a loss. For Christmas, a florist sent flowers to inmates’ families and friends. Activists have also founded an online snack shop named Jimmy Jungle, which provides low-cost care packages for those behind bars.

Some protesters who expect to end up in prison make orders in advance for themselves, “as though they are making their own funeral arrangements,” said Jimmy Jungle’s founder Michael, who asked not to use his last name due to fear of repercussions from authorities.

Some supporters gather at courthouses after trials and chase after police vehicles as they transport convicted protesters. The well-wishers wave and shout to the people inside, hoping they will notice and know that they are not alone.

One 19-year-old university student majoring in philosophy recently spent three hours waiting to “send off” two university students. He stood shivering with dozens of his classmates outside a courthouse, outnumbered by police who lined the streets. Social distancing warnings blasted from the speakers.

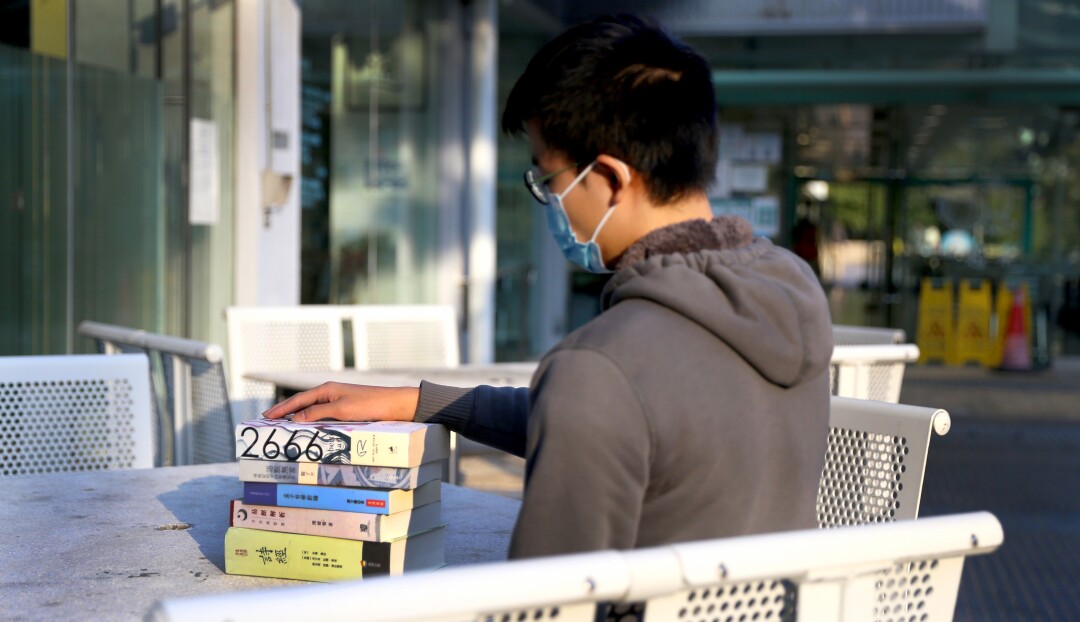

Five Mouths, a 19-year-old philosophy student, has prepared books to bring to prison.

(Rachel Cheung / For the Times)

At last, a van came out and sped down the road. The student, who went by the nickname Five Mouths for fear of having his statements used against him in court, never saw the faces hidden behind tinted windows. “It was three hours of wait and they were gone in two seconds,” he said.

Five Mouths is out on bail himself after being charged with unlawful assembly for raising his middle finger at riot police when he saw them stopping and searching a teenager in November 2019. He said police slapped him repeatedly during questioning and mocked him for carrying antidepressants.

During his first trial in December, Five Mouths was represented by two volunteer lawyers facing a prosecution team of five. He paid over $2,500 for a psychiatric assessment required to prove his depression. The prosecution delayed disclosure of evidence for weeks, leaving the defense lawyers with little time to prepare.

“It’s a form of mental torture because you don’t know what will happen to you,” Five Mouths said. While awaiting the next hearing in his trial in March, he reports to the police to fulfill his bail conditions once a week, sometimes for nine hours at a time.

He has tried to stay calm by taking medication and preparing for prison, he said, setting aside six thick books of Chinese philosophy and literature and asking a friend to send them when the time comes. He expects an eventual sentence of nine to 13 months.

Five Mouths does not regret his actions. He chose his nickname — which also spells out the word “I” in Cantonese — as a reminder to speak up for others and remain true to himself, he said: “From a practical angle, it’s not worth it. But the moral value of what I did was consistent with my values.”

When Lau, the social worker, was released from prison, he found a crowd of strangers hoisting a banner of his face, chanting a welcome. He blinked away tears in the sun.

Since his release, Lau has continued doing social work, though he lost his job and may soon lose his license. A social worker helped Lau leave a gang as a teenager, inspiring him to pursue the same profession. He wanted to change young people’s lives, to “walk with those who are suffering and marginalized,” he said.

Instead, he has spent the last year sitting in courtrooms, watching as the youth he worked with went one by one to trial, then to detention. Four days a week, he visits them in various detention centers, all the while aware that he could soon be inside again. Lau faces a sentencing hearing at month’s end and if his appeal is denied, he will be sent back behind bars.

Yet to him, the protests and their aftermath have reinforced a sense of injustice.

“During the social unrest, it became clear who are the powerless,” Lau said. “They lose families, their studies, their careers and even their futures.”

As a social worker, Lau believed in nonviolence. But he understood why some protesters had thrown bricks and set fires during the prior unrest.

Riot police officers pin down a protester during a demonstration in Hong Kong.

(Willie Siau / Getty Images)

“The older generation of Hong Kong people take pride in our independent judiciary system and status as a financial hub. They are the two swords that made Hong Kong the metropolitan city it is. But we have not benefitted from its economic prosperity in any way, and instead of finding justice, we are crushed by the judiciary,” Lau said. His generation had lost trust in the government and tried to resist through “all possible means.”

The result in 2020 was “blatant intervention from the Chinese Communist Party and collapse of civil society beyond our imagination,” he said. He could not see what else lay in Hong Kong’s future except further crackdown, with a mass movement shattered and each individual bearing punishment alone.

“Ultimately, when you are in prison,” he said, “you are on your own.”

Cheung is a special correspondent.