The fierce global debate set off this week by a thought-provoking paper – “The Longer Telegram: Toward a New American China Strategy” – has underscored the urgency and difficulty of framing a durable and actionable U.S. approach to China as the country grows more authoritarian, more self-confident and more globally assertive.

The 26,000-word paper, published simultaneously by the Atlantic Council and in shorter form by Politico Magazine, has served as a sort of Rorschach test for the expert community on China. The reactions have ranged between critics, who found the paper’s prescriptions too provocative, to proponents, who lauded its ground-breaking contributions.

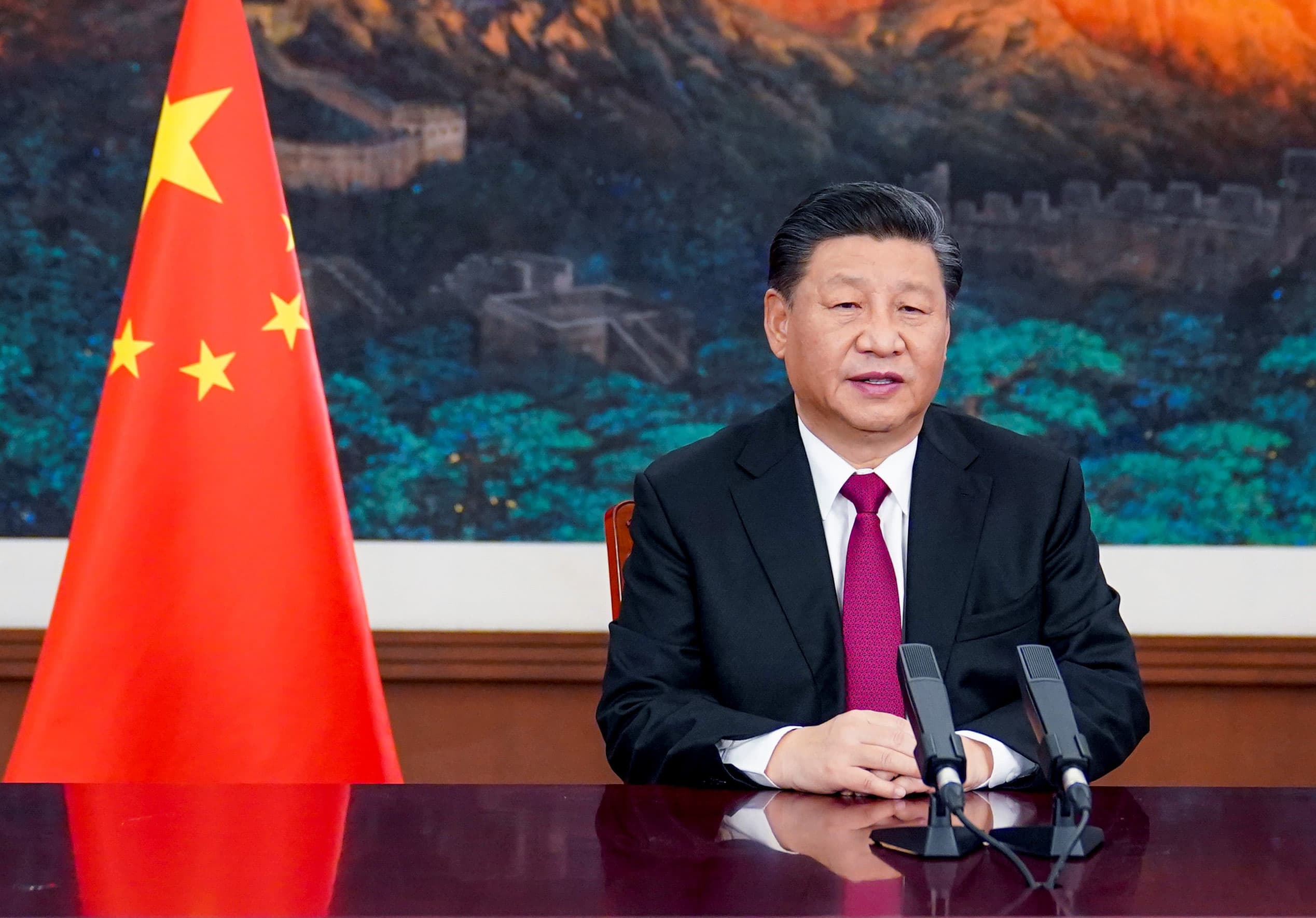

Beijing took notice, not least because of the author’s apparent familiarity with Communist party politics and focus on President Xi Jinping. China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson accused the anonymous author of “dark motives and cowardliness” aimed at inciting “a new Cold War.”

Writing in the realist, conservative National Interest, former CIA China analyst Paul Heer seemed to agree, debunking the singular Xi emphasis “a profoundly misguided if not dangerous approach.”

Financial Times’ columnist Martin Wolf agreed with Anonymous that China “increasingly behaves like a rising great power ruled by a ruthless and effective despot,” but his critique was that the author’s myriad goals aren’t achievable due to China’s economic performance and untapped potential.

Having digested the most spirited debate evoked by any of the growing industry of China strategy papers, I come down on the side of Sen. Dan Sullivan, Republican of Alaska, who lauded the paper during an extraordinary speech on the Senate floor.

Sullivan’s credibility grows out of his history as Marine veteran, former Alaskan attorney general, and former National Security Council and senior State Department official dealing with business and economy.

“‘The Longer Telegram,’ while not perfect,” he argued, standing beside a blow-up reproduction of the paper’s cover balanced on an easel, “sets out what I believe is certainly one of the best strategies I have read to date about how the United States needs to address this significant challenge that we will be facing for decades.”

“I hope my colleagues, Democrats and Republicans, all have the opportunity to read this, analyze it. For like Kennan’s strategy of containment, our China policy, to be successful, also needs to be very bipartisan and ready to be operationalized for decades.”

The three elements of The Longer Telegram’s approach that should stand the test of time are:

- The urgent need to understand China’s internal policy and political dynamics better to succeed.

- The reality that a declining U.S. won’t be able to manage a rising China, irrespective of strategy.

- The focus on reinvigorating and reinventing alliances, not from any sense of nostalgia, but because no policy will succeed that doesn’t galvanize partners in creative new ways.

Let’s take each of these priorities in turn.

First, the most innovative and controversial idea contributed by The Longer Telegram is its focus on China’s leader and his behavior.

“U.S. strategy must remain laser-focused on Xi, his inner circle, and the Chinese political context in which they rule,” the paper argued. “Changing their decision-making will require understanding, operating within, and changing their political and strategic paradigm.”

The most paper’s most virulent critics took on this Xi focus. Some argued that the author overestimated Xi’s role, and others quibbled with the notion that China would become a more cooperative partner under more moderate leadership if Xi were replaced over time.

Others warned that China would regard any U.S. policy focused on Xi as a dangerously escalatory effort at regime change.

Yet those points miss the author’s more significant and irrefutable point: no American strategy toward Beijing can succeed without a better understanding of how China’s decision-making unfolds.

“The core wisdom of Kennan’s 1946 analysis was his appraisal of how the Soviet Union worked internally and the insight to develop a US strategy that worked along the grain of that complex political reality,” writes Anonymous. “The same needs be done to address China.”

The author’s own informed view is that Xi’s concentration of power, his campaign to eliminate political opponents and his emerging personality cult have “bred a seething resentment among large parts of China’s Communist Party elite.”

Whether or not you agree with the author’s view that China has underrecognized political fissures and fragilities, the real point is that the U.S. must invest more in understanding such dynamics. One of Beijing’s advantages in the competition is its insight into America’s painfully transparent political divisions and vulnerabilities.

On the second point, President Biden’s first foreign policy speech underscored his alignment with author’s second key point. “U.S. strategy must begin by attending to domestic economic and institutional weaknesses,” writes the author.

“We will compete from a position of strength by building back better at home,” President Biden said.

Nothing will be more important.

Finally, and this was at the heart of the Biden speech, the author argues that the U.S. needs to galvanize allies behind a more cohesive and coherent approach. That will be hard to pull off, as a great many U.S. partners now have China as their leading trading partner.

Forging common cause among traditional U.S. partners and allies will take an unprecedented level of global engagement and give-and-take – and an acceptance of the reality of China’s economic influence.

Critics singled out other elements of the paper. For example, some called out the author’s appeal for “red lines” in the relationship, on matters ranging from Taiwan to the South China Sea, as particularly perilous.

Others considered the author’s call for greater efforts to peel off Russia from its deepening ties with China as folly.

Yet both would merely be a return to sound strategic practice à la Henry Kissinger. The private sharing of red lines can head off miscalculations. Their enforcement can be measured and proportionate.

You also don’t have to love Vladimir Putin to recognize that Russia’s increasingly close strategic alignment, military cooperation and intelligence sharing with Beijing has been a profound U.S. foreign policy failure.

We published the Longer Telegram at the Atlantic Council, where I am president and CEO, and I admit to a certain bias regarding the paper’s value. I am glad it has stirred a global discussion, with criticisms and positive suggestions.

How we tackle China is a challenge as complex as it is critical. There would be no better time for this debate.

Frederick Kempe is a best-selling author, prize-winning journalist and president & CEO of the Atlantic Council, one of the United States’ most influential think tanks on global affairs. He worked at The Wall Street Journal for more than 25 years as a foreign correspondent, assistant managing editor and as the longest-serving editor of the paper’s European edition. His latest book – “Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Most Dangerous Place on Earth” – was a New York Times best-seller and has been published in more than a dozen languages. Follow him on Twitter @FredKempe and subscribe here to Inflection Points, his look each Saturday at the past week’s top stories and trends.

For more insight from CNBC contributors, follow @CNBCopinion on Twitter.