If it wasn’t for the face masks, one would never guess that a pandemic had started here.

Jianghan Street, a famous pedestrian shopping avenue lined with colonial buildings, was bursting with Chinese New Year cheer. Red lanterns hung from street lamps, storefronts displayed holiday sales, families snacked on hawthorn candy skewers and bought clothes and gifts for the season.

Decorations for the Chinese New Year hang in a store in Wuhan, China.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

One year ago, these streets were a barren landscape of fear. Wuhan’s residents shrank indoors, forbidden from leaving, as a virus claimed thousands of lives. Hospitals were overwhelmed, patients struggling to breathe in waiting rooms and parking lots, while relatives cried for help on the internet and through government hotlines that were often impossible to reach.

Few in Wuhan — a factory city on the Yangtze River — want to remember that time. Similar scenes have replayed across the world as COVID-19 spreads, killing more than 2.3 million people so far. But here where the pandemic began, life has returned to familiar rhythms. Fewer than 10 infections have been reported since last April. Beijing has turned Wuhan into a symbol of its victory over the coronavirus, arresting and silencing those who question its narrative and blame the government for mishandling the initial outbreak.

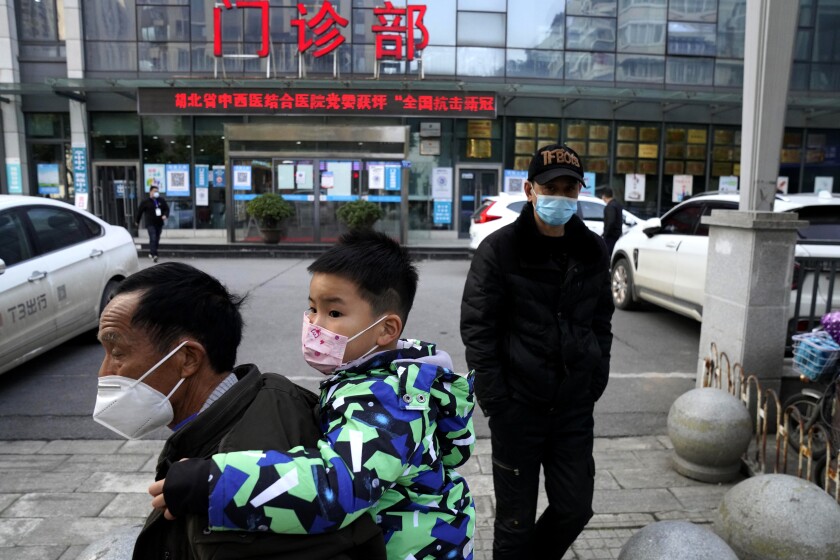

A man carries a child past the Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine in Wuhan on Jan. 29.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

So much on the surface suggests the city has healed: Two young women sat on the sidewalk, chattering about boyfriend problems. An old man in an orange coat and white beret nudged his wife’s wheelchair into the sun, offering his arm to her as she gazed at the laughing crowds. But a sense of disquiet lingers beneath.

“It’s like we’ve all taken an anesthetic,” said Mary Xu, 56, a therapist in Wuhan. “People don’t want to face it. They are numb and avoidant.”

No one around her wanted to talk about the one-year anniversary of Wuhan’s lockdown, she said. Whenever it came up in conversation, someone would quickly change the subject, sometimes proposing a toast: “Cheers, we’re still alive!”

“People have built up a shell to protect themselves,” said Xu.

She has counseled many patients still racked with guilt and grief, especially those who lost loved ones in Wuhan’s early lockdown days. A shortage of tests and hospital beds meant many died without confirmation of whether they had COVID-19 or not.

Wuhan residents walk past government propaganda painted on a wall on Feb. 4.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

One woman’s mother and husband died within days of each other. A wife had panicked when her husband was quarantined. She threw away everything he had touched at home. Sitting alone, she felt unable to breathe, afraid of dying with no one knowing. Xu had counseled her over the phone.

Another woman had spent days begging for an ambulance — at that time private cars were also barred from Wuhan’s streets — for her father, but once it came she could not get him a hospital bed. She brought him home, where he lay on the first floor because she didn’t have the strength to carry him up the stairs.

“He passed away there in front of her. She was making congee for him,” Xu said. “She didn’t get to say goodbye.”

To ease such trauma may take years. It is easier for many of Wuhan’s residents to block memories of the darkest days. There is also a shortage of good psychologists, Xu said. Many are too quick to diagnose problems rather than explore the anger, sorrow and fear patients feel. Shame, too, is prevalent.

“There is a kind of stigma,” she said. Even she felt embarrassed asking relatives who’d lost family members last year how they were doing. Those who had been infected with the virus and survived did not talk about it. “It’s a feeling of guilt, and the fear that people will shun you,” Xu said.

There are also political reasons to forget.

“Chinese people have always been living through crises. Why should they react any differently this time?” said Ai Xiaoming, a prominent retired professor of literature and women’s studies and a documentary filmmaker in Wuhan. Her documentaries often cover censored social issues including “reeducation through labor” camps and village uprisings against corrupt party officials.

A child wearing a mask rides on a skate scooter in Wuhan, China, in January.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

Time and again, China’s laobaixing, the common folk, survive tragedy caused by government irresponsibility and tell themselves just to be thankful they are alive, Ai said.

“This is a remnant of the Cultural Revolution and Great Famine,” she said, referring to Mao Zedong-era social upheaval and mass starvation that killed tens of millions in the 1960s and ’70s. Many older Chinese people contrasted today’s wealth and stability with the cannibalism that became common during the famine, and felt grateful for where they were.

“But if you think that way, then we are using beasts as a standard,” Ai said. “As long as we don’t cannibalize each other, we are doing well and we should be thankful? No. We should use human life as a standard.” Others want the government to be held accountable for not reacting quickly enough to contain the virus in the early days, she said, but dare not demand it: “The cost is too high.”

Ai has struggled with how much to say to journalists. “Everyone is taking a risk to speak, and then you can’t say all that you want to say. Is that how an intellectual should behave?” she said. “I am ashamed.”

One of the first Wuhan residents to post videos from its hospitals revealing the scale of the outbreak was Fang Bin, who spoke with The Times after an initial arrest on Feb. 4, 2020, then was reportedly arrested again five days later and has been missing ever since.

On that day, he had posted a 12-second video in which he said: “All citizens resist, return governance to the people.”

A woman walks past Lunar New Year decorations outside a shop in Wuhan, China, on Feb. 1.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

Another activist, an ex-lawyer named Zhang Zhan, 37, was detained in May after posting videos online about the Wuhan outbreak. She was sentenced to four years in prison on charges of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” in December.

She has been on a hunger strike since June and has lost 44 pounds, according to one of her lawyers. Authorities were force-feeding her with a tube while keeping her hands restrained so she could not remove it, he said.

“Lawyers are like puppets here,” said Zhang’s lawyer, who asked that his name not be used because he has been forbidden to speak with foreign media. Even defending Zhang felt like a farce at times, he said, like he was “going along with the performance” and legitimizing a sham court. “Outside of the law,” he said, “is another, more terrifying hidden system that’s functioning.”

A recent uptick in arrests of activists and disbarring of human rights lawyers has made the price of speaking against the government narrative clear.

Last week, women’s rights activist Li Qiaochu, 27, was detained in Beijing. Li had spent four months in incommunicado detention last year due to affiliation with her partner Xu Zhiyong, a civil rights activist and legal scholar who wrote an open letter last year calling on Chinese President Xi Jinping to step down.

“In the name of ‘stability maintenance’ the Wuhan Public Security Bureau threatened and denigrated doctors who tried to reveal the truth about the coronavirus,” Xu wrote in the letter. “The coverup of the unfolding crisis in Wuhan contributed directly to what is now a national disaster. Stability at any price — at the price of the freedom of the Chinese, their dignity, as well as their pursuit of happiness? For all of that, is the system really all that stable?”

Residents and their children near Chinese Lunar New Year decorations in Wuhan.

(Ng Han Guan / Associated Press)

Xu has been arrested with the charge of “subverting state power,” with a potential sentence of 15 years to life in prison. Li, who was rearrested after speaking publicly about Xu’s case and his abuse in detention, has been given the same charge.

For some in Wuhan, memory is a nagging, daily pain.

Zhong Hanneng, 68, lost her son Peng Yi to COVID-19 in February 2020. She also was infected and was quarantining at home, unaware of his death until a month later. Only then did her daughter-in-law tell her how she had struggled to find Peng, 39, a hospital bed and transportation.

It took days of negotiation before they’d gotten a small open-bed truck to drive Peng to a medical center. He had ridden in the back with his high fever, exposed to the winter rain for more than an hour on the way.

At the hospital, he’d been neglected by the overwhelmed staff, given only a carton of milk after hours of begging for food, Zhong said. In his last moments before losing consciousness, he’d sent many unanswered messages asking hospital staff for help.

Zhong only learned about this recently, when she received Peng’s cellphone and looked through the contents.

“I’m always thinking of him alone, how he died with no one around him. That kind of helplessness. That kind of fear,” Zhong said. “It’s hard for me to pass every day. I can’t stop thinking about it. I can’t get over this.”

Zhong was angry that she had believed the government messages she saw on TV about the virus being “controllable and preventable,” with no danger of human-to-human transmission. It was at this time last year, the days before Chinese New Year, when her family had gone out in crowds believing they wouldn’t get sick.

“If only they had told us earlier. We had no warning. We always believe whatever they say,” Zhong said. “We were too stupid, too childish.”

Zhong has filed two complaints against the local government seeking accountability for her son’s treatment but received no reply. He had been a well-loved elementary school teacher. His colleagues and the school’s Communist Party secretary had tried to help him get a hospital spot when he was sick. But once he died, they stopped communicating with Zhong’s family, she said.

The only relief she felt was when she did eight sessions of online therapy. But she was unable to contact the therapist again after those sessions ended. She had felt uncertain about what she could say online. When she expressed anger at the government during their sessions, the therapist had seemed to hesitate and pull away, she said.

“They were afraid to listen,” she said.

Wuhan was back to normal. She was not. And that made her dangerous.