Beeple is an artist.

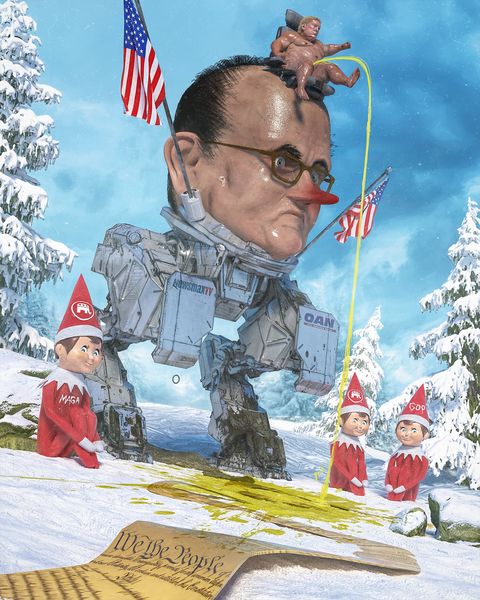

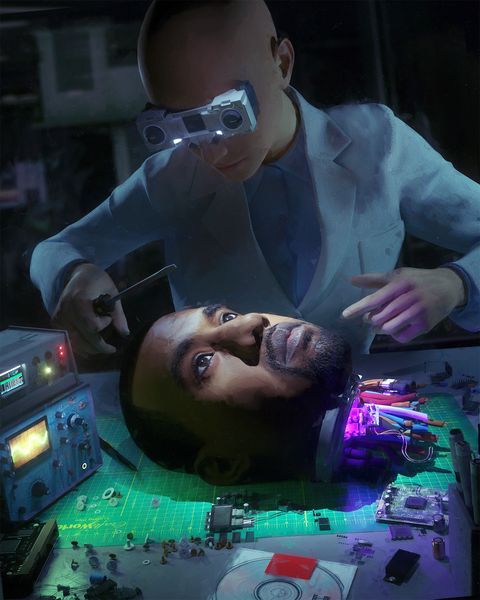

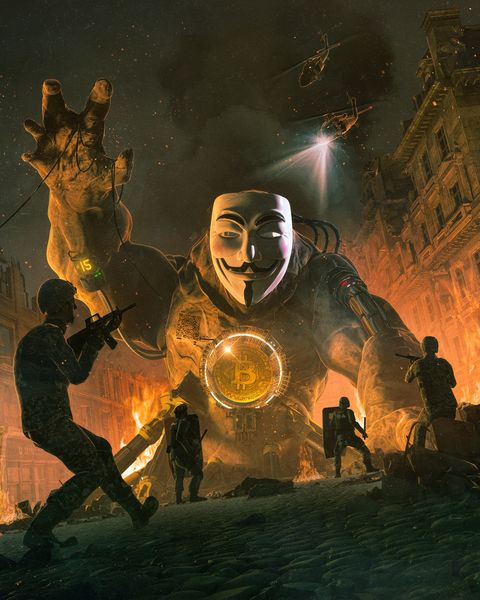

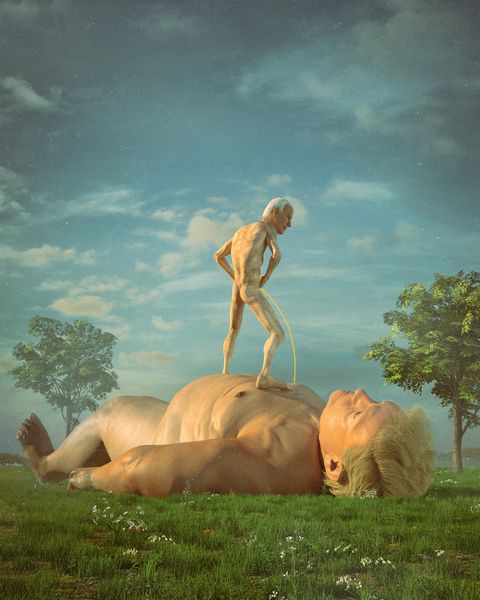

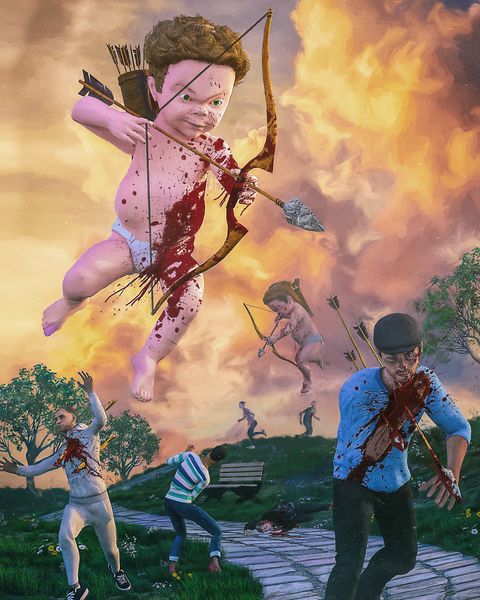

He makes digital art—pixels on screens depicting bizarre, hilarious, disturbing, and sometimes grotesque images. He smashes together pop culture, technology, and postapocalyptic terror into blistering commentaries on the way we live. A recent frame depicted Donald Trump wearing a leather mask and stripper’s pasties, taking a whip to the coronavirus bug (title: “Trump Dominating Covid”). On the day Jeff Bezos announced he was kicking himself upstairs, Beeple imagined the Amazon founder as a massive, threatening octopus emerging from the ocean as military helicopters circled above (“Release the Bezos”).

Beeple has 1.8 million Instagram followers. His work has been shown at two Super Bowl halftime shows and at least one Justin Bieber concert, but he has no gallery representation or foothold in the traditional art world.

And yet in December the first extensive auction of his art grossed $3.5 million in a single weekend.

That money? It went to one Mike Winkelmann, thirty-nine, father of two, husband of a schoolteacher, resident of a Charleston, South Carolina, suburb, driver of a “fucking Toyota Corolla piece of shit.”

See, Beeple is Mike Winkelmann. Mike Winkelmann is Beeple. And in the weird worlds of high fashion, fine art, and cryptocurrency, it doesn’t get any weirder than this story.

Expectations for December’s auction were on the high side of earthbound. That Saturday afternoon, Winkelmann—who looks like a young Bill Gates dressed in Steve Kornacki cosplay and speaks with a Wisconsin accent straight out of an old SNL sketch—and his wife, Jen, went to his brother’s backyard to monitor the auction. Pretty quickly, his brother, a former electrical engineer for Boeing, was scrawling sales figures on a whiteboard while the kids ran around the firepit, oblivious to the fact that every half hour another piece of Beeple’s digital art was selling for more than $100,000.

Jen was in a state of disbelief.

The artist himself couldn’t bear to watch, and mostly spent his time tweeting out photos of the next pieces and answering questions from would-be buyers. At one point, he received a direct message from the musician Sean Lennon—son of John—who tweeted: “I can’t manage to do anything today but watch these mfing @beeple auctions tick down,” adding: “god damn Beeple Mania have mercy.”

Ten pieces sold that day, and another eleven on Sunday, including the grand finale: one long, continuous digital loop of every single piece auctioned off that weekend. A stunning bid came in with one second remaining on the clock. “The Complete MF Collection,” as Beeple dubbed the work, sold for $777,777.

It was one of those things you hear about and think, Do I have any idea what’s going on in the world? Is this normal and I’m just waaaayy out of touch, baking my bread while people are out there buying digital artwork using cryptocurrency?

From Beeple?

Back up.

What, pray tell, are these collectors even buying? Why would someone pay $777,777 for an MP4? Couldn’t you watch that on Instagram for free?

Theoretically, yes, but the crypto art scene uses blockchain technology to authenticate and identify a single, unique piece of digital art. To understand how that piece of art sells for the price of a one-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn, one needs a brief primer on something called nonfungible tokens, or NFTs—digital goods that are bought and sold on emerging websites like Nifty Gateway, which hosted the Beeple auction. Nifty Gateway was founded in 2018 by the absurdly named Duncan Cock Foster, twenty-six, and his twin brother, Griffin. When asked to explain NFTs, Duncan used this analogy: Imagine you owned a pair of expensive Air Jordans. If Nike went out of business, those sneakers wouldn’t suddenly disappear from your closet. Why should digital goods—like a Fortnite skin or an original Beeple—be any different?

And so: Nifty Gateway—one of several upstart online marketplaces in a field that also includes sites called MakersPlace and SuperRare—mints a unique NFT, assigns it to a piece of digital art, and stores it forever in that company’s custodian wallet. Anyone with an Internet connection can log on and see who owns that piece.

Nifty Gateway was acquired in late 2019 by a more famous set of twins, Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, best known as the guys who said Mark Zuckerberg stole their idea for Facebook. The Winklevii rode the cryptocurrency wave to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index and are bullish on NFTs. They ask why collecting digital art should be any different from collecting rare baseball cards. An item is worth what the market will pay.

The fact that you can’t hang the art on the wall is beside the point, they contend. “Physicality is a bug, not a feature,” says Tyler. “There was no scarcity in ones and zeroes until you enter with the blockchain.”

Put another way: Anyone can view a Beeple on Instagram. But blockchain makes it collectible.

Duncan Cock Foster—that’s seriously the family name—and his brother had launched Nifty Gateway with the hope of mainstreaming the market for NFTs, which had been complicated to buy and sell. (Most marketplaces required users to have Ethereum wallets.) For the December auction of Beeple’s work, they’d hoped to generate $500,000 in sales for the weekend. But when they crushed that number on Friday night, things started to get interesting. Cock Foster had been monitoring the proceedings from his apartment in New York’s Chinatown and was stunned—by the total figures but also by what this drop meant for the crypto scene. “We all felt like we were witnessing history,” he says. “This is one of the things, in retrospect, where people will say: How did we miss this?”

Or maybe NFTs are just the next Beanie Babies. It’s too soon to tell. Dan Kelly of the industry publication NonFungible.com, which tracks sales of NFTs, estimates the crypto art market to be at more than $20 million, which isn’t massive until you realize that most of that trading happened in the last twelve months. Hackatao, an artist duo who formed in Milan in 2007, sold $250,000 worth of NFTs last year on SuperRare. In October 2020, Christie’s—the venerable auction house—sold a physical canvas by the artist Robert Alice that quietly came with an NFT, Christie’s first shot at the crypto market; the lot was estimated to sell for $12,000 but traded for more than $130,000. Meanwhile, the week after Beeple’s record-breaking December drop, an artist called Pak did a collaboration with Trevor Jones that brought in $1.3 million, which led the blue-chip auction house Sotheby’s to tweet at Pak: “We are intrigued…”

Of that exchange, Cameron Winklevoss says, “That’s like Barnes & Noble reaching out to say, ‘We saw your best seller. Do you want to talk?’”

A few weeks after his record-breaking auction, Winkelmann FaceTimes me from his home office outside Charleston, where he moved in 2017 to escape the Midwest winters. He’s dressed in a beige half-zip mock-neck sweater in a room of beige carpeting.

There is no art hanging on the walls. Behind him you can see side-by-side sixty-five-inch flat-screen televisions—one tuned to CNN, the other to Fox News. “I never change the channel and they’re always on mute,” he says. The TVs, he says, are a “window to the outside world.”

The home is big and airy with a view of a palmetto tree, which makes his setup even more unlikely. Cables run from his computer monitor to the bathroom next door through a crude hole in the wall. Doing the work it takes to render 3D animation, his computers give off so much heat that he’s had to put them on a wood platform over the bathtub, and he jury-rigged an industrial AC unit over the sink that vents into the attic.

His neighbors have no idea what he does, he says, which is probably good. Late last year, the revolutionary company Boston Dynamics posted a video of robots that could dance. It went viral, and Winkelmann put his spin on the moment, dropping the robots into a virtual strip club where patrons threw dollar bills at them.

Another piece, last February, featured a lactating Mickey Mouse (title: “Disney+”).

Scott Glassgold, an L.A.-based producer, who was behind the 2018 Pedro Pascal (Game of Thrones, Narcos) sci-fi movie Prospect, is working with Janelle Monáe’s production company on a TV pitch based on Beeple’s work (to be written by Philip Gelatt of Netflix’s Love, Death & Robots). He marvels at the dichotomy between Beeple’s art and Winkelmann the man. When Winkelmann travels to L.A., the two often drop in to a Koreatown diner for hamburgers, and Glassgold compared the experience to the movie Fight Club:

“You sit down, you’re like, ‘I’m having lunch with Ed Norton.’ We’re talking about family and regular things,” he says. “Then you leave and get in your car and see the image he posted, and it’s this crazy bizarre thing. It’s like, Is that the same person? Was that Tyler Durden or Ed Norton?”—referring to Norton’s Jekyll-and-Hyde performance in the 1999 film.

Winkelmann grew up in North Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, a town of 5,000 people about an hour outside of Milwaukee. His dad was an electrical engineer; his mother worked at a local senior center. Winkelmann graduated from Purdue in 2003 with a computer-science degree but no artistic training. (He chose the name Beeple after a 1980s toy whose nose lit up in response to light and sound, which was loosely connected to the kind of early art he was making.)

After a brief career designing corporate websites, Winkelmann heard about an artist in the UK who’d gotten attention by doing a sketch every day. Winkelmann ran with the idea, but in animation—using a program called Cinema 4D to do a daily study. He called his project “Everydays.” The series launched on the first of May, 2007, and in the years since, it has evolved from rudimentary cubes to images of a dystopian future with a wink at the culture. Alongside things like a Michael Jackson AI gestating a human baby, his art has evolved to include sharp critiques of government and social media (including a zombie Mark Zuckerberg). He professes not to have spent much time examining his own psyche. “Yeah, the sexual milking, lactating stuff?” he said. “I don’t know where the hell that shit’s coming from.”

Winkelmann eventually focused on freelance projects for companies like Possible Productions in Los Angeles, which does graphics and animation for live events, including the MTV VMAs and the Super Bowl. (When Shakira walked through digital fire at the Super Bowl, that was Beeple.) He has also, in his words, done “lame” work for Apple but also something for Elon Musk’s SpaceX that was so “friggin’ sweet,” he’d tell you about it if he weren’t subject to a nondisclosure agreement. But he kept up the “Everydays”—for thirteen years now and counting—and he hasn’t missed a single day. Not for his wedding or the birth of his two children or a cross-country move from Appleton, Wisconsin, to Charleston.

The stunning visuals have attracted a diverse audience online. In 2018, Winkelmann received a direct message from Florent Buonomano, an artistic director at Louis Vuitton, who’d shared the work with his boss, artistic director Nicolas Ghesquière (“the design leader of his generation,” according to Vogue). Winkelmann knew so little about fashion that his first thought was: Is Louis Vuitton still alive? He was surprised to find out that while Vuitton had passed away in 1892, he was corresponding with the artistic director of an iconic luxury house with 160 years of rich history.

Vuitton was hoping to digitally print some of Winkelmann’s art onto a collection that would debut in a runway show at the Louvre. (“I was immediately captured by Beeple’s futuristic universe,” said Ghesquière, who later collaborated with Winkelmann on digital window displays for some of the global Vuitton boutiques. “His work resonates strongly with today’s world.”) Vuitton paid Winkelmann a flat fee, but the artist didn’t believe any of this was real until he was sitting in the Louvre and the first model rounded the corner wearing one of his images across her body.

Cate Blanchett and Alicia Vikander were sitting front row. So was Winkelmann—in a suit he bought off the rack at Zara after his wife told him he couldn’t wear a brown fleece pullover he found in his closet. At the after-party, he ogled passed hors d’oeuvres beside Spike Lee and Michael Fassbender but didn’t dare introduce himself. “What the fuck am I going to say to Spike Lee? ‘Hi, I’m Beeple.’”

Selects from Beeple’s “Everydays” would appear on thirteen of forty-five pieces in the Spring/Summer 2019 ready-to-wear collection. Unrelated, a few months later, controversial comedian Joe Rogan reposted a Beeple animation that depicted Kim Jong Un as a supervillain armed with tentacles tipped with Hillary Clinton’s face, calling the artist’s work “amazing shit” and directing his followers to follow him.

Despite the attention and his growing reach, Winkelmann never considered selling any of his work. Or rather, he didn’t really know how to sell it. This is a common problem. As John Crain, the cofounder of the NFT marketplace SuperRare, explained: “A lot of supertalented digital artists don’t fit the model for the contemporary art world. They don’t go to Art Basel. They’re active on GIF communities. They weren’t monetizing the work as fine art. They might have sold T-shirts on a Linktree.”

Then, in the latter half of 2020, Winkelmann started to hear about blockchain technology and the emerging crypto art market. A rep for Nifty Gateway had sent him a message in September 2020, noting Beeple’s popularity and asking if he’d consider doing a drop. Winkelmann ignored the message, thinking it was a random solicitation. But after seeing other artists he knew of making, in his words, a “buttload” of money, he finally did his homework. “If that guy is making a buttload of money,” he said, “I can probably make a shitload of money.”

In October, he tested his theory, auctioning off three pieces—which crashed the Nifty site. One of those digital pieces, an animation titled “Crossroad,” was unique in that the image would change depending on who won the November presidential election. It sold for $66,666.66.

(Of the seemingly random price tags with repeating digits, one collector told me there is an “underlying art to bidding style” that involves both numerology and a little bit of peacocking. Winkelmann added his own theory: “This relates to the sort of ‘cryptography’ side of the space. The blockchain is really sort of like a giant number puzzle. I think that’s why you often see a much bigger emphasis placed on special numbers.”)

Despite the impressive receipts, Winkelmann couldn’t quite shake the feeling—however fleeting—that without some physical object to go along with the NFT, he was kinda maybe selling “magic beans.”

“Why would you spend $5,000 on an MP4? The difference between owning it and not owning it was just an email that said, ‘You won.’ I can see how you would call bullshit on that.” Despite what Tyler Winklevoss said about hardware versus software, other artists had had similar reservations, solving this problem by sending prints to winning bidders. But a print was such a different experience from the digital animation.

Within days, Beeple had an idea to quiet skeptics and juice bidding. Inspired by collectibles like the vinyl toy market, Winkelmann and his wife set about designing a high-end physical object to go along with each sale. What they came up with was a marvel; picture a small LCD screen with a titanium back that displays the piece you just bought on a slow-moving loop. It’s like someone had asked Steve Jobs to redesign the Lucite box typically used to display baseball cards, but make it electric. Each one costs $500 to produce and is numbered and authenticated, with a front-facing QR code that takes you to a website that lists the provenance of that piece of art—who owned it before, and who owns it now.

“When I think prize,” Winkelmann said, “I think something you get in a fucking Cracker Jack box. I wanted to make this thing feel like it is the artwork. And it’s super tightly integrated with the NFT so that it feels like the same thing.”

Winkelmann set his next auction—the eventual record-breaking sale—for the weekend of December 11. While the catalog copy was predictably brash, reading: “hahahah, ok so we’re going balls deep on this motherfucker,” elements of the auction were fairly old-fashioned. Much in the way a traditional auction house would, Winkelmann arranged to preview (by Zoom or FaceTime) the twenty or so pieces for about a dozen high-end collectors in the crypto art scene, including a mysterious buyer calling himself MetaKovan (who is rumored to be in Singapore) and another, a twenty-seven-year-old crypto baller named Tim Kang, the son of Korean immigrants who left his job at Deutsche Bank to go all-in on blockchain, and saw the titanium object as a work of art in and of itself, and a sea change for the crypto marketplace.

“It was like opening up your first iPhone from the box,” Kang told me.

On the first day, Beeple auctioned off three numbered “open edition” pieces, each priced at $969, and set the time limit for five minutes. Nifty Gateway had added nine additional servers to handle the expected traffic, and the site held. Within five minutes, $582,000 worth of art had been sold.

Ten individual pieces would be auctioned off on Saturday and eleven on Sunday. Over the next two days, according to Nifty Gateway, twelve bidders would each place bids of more than $100,000. In the heat of the auction, a mystery soon unfolded. Users were repeatedly outbid by a series of buyers whose screen names all shared a single, curious connection: Each was named for a hill in Rome. An Internet sleuth later revealed that these pseudonyms all belonged to a single collector who’d purchased twenty of the twenty-one pieces.

That collector? The elusive MetaKovan.

Kang succeeded in purchasing just one piece at auction, the finale—the complete collection, which he bought for $777,777, making it the most expensive NFT in history. Reached by phone in January, Kang (who now lives in Los Angeles) revealed for the first time that he never expected to win. His previous bid was $377,777. With one second left in play, he added $400,000 to his offer, throwing down a very expensive gauntlet. Per the auction’s rules, his bid reset the clock for an additional five minutes. “I assumed [MetaKovan] would outbid me—that was my threshold and I’d be out,” Kang said. He watched the clock nervously, thinking, He’s gonna outbid me, right?

“A lot of people, from an outsider perspective, they don’t understand why I did it. They might see it in a reckless way. That’s why I’m shitting my pants. I never really came out publicly. But I’m proud of it. I believe that it really validated the space. What I really wanted to stand for—when I put in that bid—was to show the world that this is the paradigm, this is the future.”

The sale was captured in perpetuity on the Beeple Twitter account. In a short video, the artist himself can be seen celebrating in his brother’s backyard as two people spray him with Champagne. Winkelmann cowers and giggles, repeatedly saying: “That’s cold as shit!”

The Beeple drop made $3.5 million—plus another $500,000 on the secondary market—in that weekend alone. Winkelmann retains 90 percent of the initial sale, and unlike the typical arrangement with a traditional art gallery, he’ll also earn 10 percent of the secondary sales. The December lots amounted to just twenty pieces from his “Everydays” series. That’s twenty frames out of thirteen years’worth of work.

As the pandemic accelerated trends toward digital everything, the same was true in the crypto art space. While a live auction could be a superspreader event, crypto buyers were able to view pieces of art as they were meant to be enjoyed: from the safety of their own phones. Nifty Gateway has done more than $11 million in sales since launching in March of 2020, with the volume growing by about 50 percent month over month.

And the traditional art market has been responding. A January 2021 article in The Art Newspaper, the art-world paper of record, noted the October 2020 Robert Alice sale at Christie’s and asked the question: Are NFTs “a new disruptor in the art market?” Georgina Adam wrote the piece, saying of NFTs: “Those from a more traditional art background will be horrified by most of the ‘art’ offered as NFTs.” There was a perception that NFTs were “garish, jaggedly drawn faces, cartoonish figures, cute kittens,” she wrote. The artist and prognosticator Kenny Schachter piled on, dismissing much of the work as something you’d see “on the back of a van,” though he did admit NFTs were attracting a new audience of art collectors.

Duncan Cock Foster predicts crypto art’s acceptance will follow a similar arc to that of bitcoin. “Bitcoin started as an asset collected by nerds,” he said. “Now it’s hedge funds and insurance companies. You’ll see art institutions collect NFTs as people get more familiar with the concept.” Or, as Beeple’s website proudly proclaims: “Not stopping until I’m in the MoMA… then not stopping until I’m kicked out of the MoMA, lol.”

In February, Christie’s announced it would auction off its first Beeple in a few weeks in collaboration with MakersPlace. While Christie’s was moving faster than some in the old world—having hosted the inaugural Art+Tech Summit in 2018, which focused on blockchain technology—Noah Davis, a specialist in the postwar contemporary department at Christie’s, suggested they were late to the NFT party.

“We’ve become educated very quickly,” he said, “and we’re still continuing to educate ourselves. I will be completely honest with you: I’m one of the youngest specialists in the department—I was born in 1989—and I feel like I’m still playing catch-up, figuring out what NFTs are and how they function so that I can explain them to our audience. It’s going to be a huge shock for a lot of them.” But Beeple’s organic market was impossible to ignore. “When we saw those numbers and the level of people transacting,” he said, “we definitely wanted access to that audience.”

For Christie’s, Beeple composed a mosaic made from his first 5,000 “Everydays”—but no LCD screen will accompany the sale. Unlike the first NFT that Christie’s sold in October—the Robert Alice canvas that happened to come with an NFT—this would be Christie’s first strictly digital piece. In short, an auction house founded in London in 1766 was about to sell a JPEG.

When asked about Kenny Schachter’s “back of a van” comment, Davis smiled, saying the same had once been said of Banksy, the celebrated graffiti artist: “There’s a perfect harmony there with the ways street art was greeted by the blue-chip, fine-art establishment. It’s almost threatening, right? Something that is new and that commands high prices can be terrifying to an established order. It’s akin to Wall Street looking at GameStop investors and thinking, No, stop! You’re not supposed to do that.” Controversy only validates the market.

“Aesthetic judgment is in the eye of the beholder,” Davis said. “We want there to be a dialogue and we want people to see this as worthy of criticism. That means it’s art. If you have a strong opinion about it, it has value. We’re all about giving visibility to this artist who clearly has something provocative to say and is also having a financially meaningful impact.”

Or not. For Christie’s, Davis said, this Beeple auction “could be just us dipping our toes into the field and seeing what happens,” adding: “A lot is depending on this lot.”

For his part, Winkelmann wasn’t feeling the pressure. Yes, he’d become the de facto face of this crypto art market, and in a way this sale would be a litmus test for the field. He was “humbled” to be a part of the moment but said the sale price is “entirely out of my hands.”

Beeple hasn’t announced the date of his own next auction—he’s focused on sending out the physical tokens from the last sale—but he imagines he’ll do spring and fall collections, just like a fashion house would. (He also promised to deliver the $777,777 prize to Kang personally, which seems appropriate considering how much the kid spent.)

It may be gauche but I had to ask: Has he spent any of the money yet? Has he replaced his “fucking Toyota Corolla piece of shit” yet?

He paused to think.

Seriously, nothing? Not a new graphics card? A new computer?

“My computer is pretty good,” he said with a laugh. “I’ll probably buy a new one soon.”

As for where his art is going next, that too remains a mystery. “If you would have asked me where it was going two years ago, I wouldn’t be like, ‘Oh, frickin’ weird boobs stuff with lactating King Jong Un.’ I try to listen as closely as possible to that tiny voice of, like, What is the picture I most want to make today?”

When the Christie’s announcement went live, I clicked on a link to preview the Beeple piece, which he was calling “The First 5000 Days.” Bidding would begin on February 25 and close on March 12. Typically an auction house would estimate the value of a piece, or maybe print “estimate on request” to add some mystique.

The text here read simply, “Estimate unknown.”

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io