At a time when the economy remains in tatters, the coronavirus continues to kill, and Texas is colder than Stephen Miller’s heart, does Joe Biden really need to worry about what we call those who are in this country illegally?

Oh yeah.

This week, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services announced it would forevermore use “inclusive” language in public and intra-agency communications. It was a warmup to an immigration-reform bill that seeks to offer a pathway to citizenship for more than 11 million people in this country without legal status.

So say adiós to any official mention of “assimilation,” and hola to “civic integration.” Time to replace “alien” with “noncitizen.” And “illegal alien,” the harsh-sounding couplet that conjures up images of intergalactic invasions? Biden’s team wants his people to instead go with “undocumented noncitizen” or “undocumented individual.”

The move has triggered expected responses from the Left and Right — the former applauds the move as a humanistic touch after four years of Trumpian ugliness, while the latter cries PC Reconquista. It’s a test balloon for the rancor to come as President Biden tries to push through the first immigration amnesty in 35 years. A dust-up over language will seem like afternoon tea once those debates get going.

“Illegal alien” has existed in the legal realm for decades, and colloquially dates back in the United States to the 1880s, when it was Chinese, Jews and Italians we were trying to keep out. But the term didn’t truly take off as part of our culture wars until it caught the attention of California’s two most prophetic voices in the state’s eternal, existential debate over illegal immigration.

Bert Corona and Barbara Coe passed away long ago — he in 2001, she in 2013. But their legacy looms large in the debate over “illegal alien.” It was their shared linguistic cudgel to advance their respective causes.

Civil rights activist Bert Corona fought against the use of “illegal alien.”

(Lori Shepler / Los Angeles Times)

For Corona, the legendary civil rights activist confronted people and institutions that used “illegal alien” to argue that their choice of words was no better than anti-Latino insults of yore like “greaser,” “wetback” and “spic.”

For Coe, a chain-smoking grandmother from Huntington Beach who jump-started America’s modern-day nativist movement, that was the point. An Anaheim Police Department civilian worker, Coe tapped into the xenophobia that always bubbles underneath California’s surface by being one of the loudest masterminds behind Proposition 187. The 1994 ballot initiative sought to make life miserable for illegal immigrants and galvanized left and right to reach the fever pitch we’re at on the matter today.

Orange County activist Barbara Coe was a driving force behind Proposition 187 in 1994.

(Iris Schneider / Los Angeles Times)

Corona and Coe represents two sides of the same California coin that seems to flip to the other side every decade or so when it comes to illegal immigration. Right now, it’s showing Corona — but don’t count out Coe just because Biden’s camp says to. Hate doesn’t disappear that fast, after all — if ever.

After decades organizing workers of all ethnicities, Corona decided to focus on the plight of undocumented workers in the 1960s. At the time, mainstream civil-rights groups still cast them as an economic and cultural threat to Latino advancement — an unthinkable position today, but the norm then.

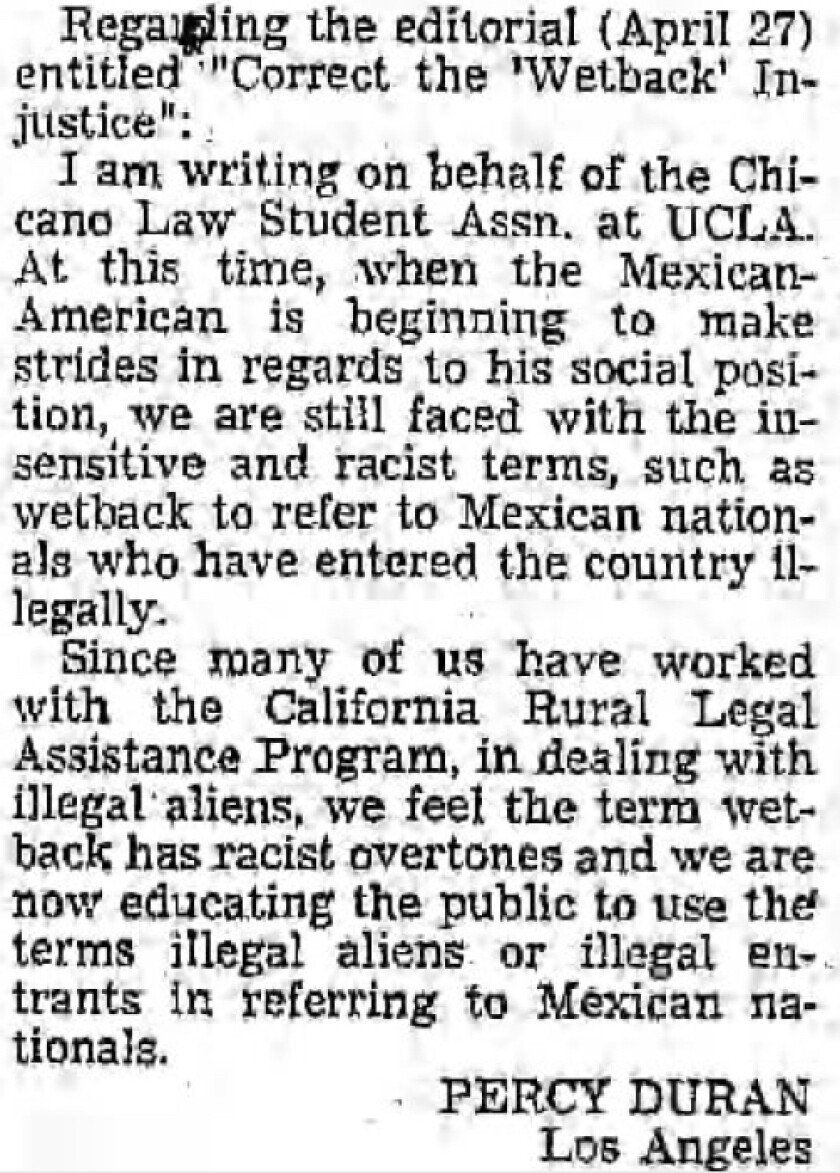

For them, “illegal alien” was anodyne and a far-better alternative than “wetback.” Take a letter that UCLA’s Chicano Law Student Assn. wrote to this paper in 1970 that argued the former phrase was better because the latter “had racist overtones.”

But even “illegal aliens” wasn’t good enough for Corona.

“He knew how devastating a term like that was,” said UC Santa Barbara professor Mario T. Garcia, who published a book-length interview with Corona about his life in 1994. “People who came from Mexico without papers were being exploited and demeaned, and it was his own sense of humanity that no one should be considered illegal.”

Corona angered the Chicano and Anglo political establishment alike with his campaigns to cancel “illegal alien.” Cesar Chavez sicced his lawyer on Corona’s group, Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, after they picketed an anti-illegal immigration action blessed by Chavez. Corona even took on Otis Chandler, the legendary former publisher of this paper, to the point where Chandler agreed to a meeting over The Times’ continued printing of the offending words.

“We stressed that such a term fed the hysteria,” Corona told Garcia. “We told them that we couldn’t understand The Times saying that it wanted to relate to the Chicano community and that it regretted the death of Ruben Salazar and at the same time using inflammatory terms such as ‘illegal aliens.’”

A 1970 letter to the Los Angeles Times by a Chicano student group asking that the paper use “illegal aliens” instead of “wetback.”

(Los Angeles Times)

Chandler promised that The Times would stop using it. The paper used “illegal alien” in news stories as recently as the early 2000s.

Corona’s advocacy, however, sparked a radical change in how Latinos and liberals thought of undocumented immigrants and the language we use for them. “Illegal alien” remained the term du jour in the American mainstream through the 1970s and 1980s, but Corona and others always pushed back with softer describers such as “unauthorized” or the well-worn refrain “no human being is illegal.”

The strategy worked: “illegal alien” began to decline in usage after President Reagan signed a 1986 amnesty that legalized more than 3 million formally undocumented immigrants. The term “illegal immigrant” took its place.

Then came Coe, whose view of the political landscape was as preternatural as Corona, although she saw a far darker scenario before her.

She knew that suburbanites and working-class whites were angry at Republicans for letting Reagan’s amnesty bill go through, so she started citizens groups where attendees would rail for hours against immigrants. Coe channeled that anger to become the emotional force behind Proposition 187, which passed with nearly two-thirds of California’s vote in 1994.

Its legacy remains two-fold: The initiative inspired a generation of Latinos to become politically active and turned California leftward — but it also triggered a wildfire of anti-immigrant sentiment that spread around the country over the past 25 years and culminated with Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential victory.

And the fuel was Coe’s invocation of “illegal aliens.” She grabbed it from the ash bins of history to light her march down the dark corridors of hate, because Coe knew how effective and inflammatory it would be.

At speeches and rallies and in interviews with the media, Coe spat out the slur (and its caustic cousin, “illegals”) or wrote it on signs (the rejoinder to the no-humans-are-illegal argument was “what part of ‘illegal’ don’t you understand?”). The official 1994 California Voter Guide, for instance, included a Yes on 187 campaign argument that mentioned “ILLEGAL ALIENS” (all-caps in the original) eight times.

Coe always claimed her language was neutral — “This is a legal issue, it is not a racial issue,” she told The Times in 1993. But it was the same dog whistle that the Trump administration learned to blow so well, said Otto Santa Ana. He’s a recently retired UCLA professor whose influential 2002 book “Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse” tracked the rise of inflammatory language like “illegal alien” and other such slurs.

Using it “became a very easy argument of double attack,” said Santa Ana. “’Illegal’ forecloses any other consideration of the status of the individual. ‘Alien’ is an ancient term from English common law. Together, the words don’t allow any subtlety.”

Anti-immigrant activists doubled down on “illegal alien,” and conservative politicians followed. But they were on the wrong side of history even before Trump gave them a temporary bump. Santa Ana was one of hundreds of academics who signed on to a campaign in the early 2010s that urged media organizations to “drop the I word” — that is to say, “illegal.” This paper agreed to do so in 2013; the Library of Congress stopped using “illegal alien” as a subject heading three years later.

Santa Ana applauds the Biden administration’s striking of “illegal alien” but warns that making it a thing of the past remains “an uphill battle.” A shibboleth that potent doesn’t just disappear with a departmental memo.

“It’s the best we can do” right now, he said. Because “until we’re invaded by Mars, we’ll continue to use it.”