Twenty five years ago, Judith Cowling was told she had two years to live when she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer.

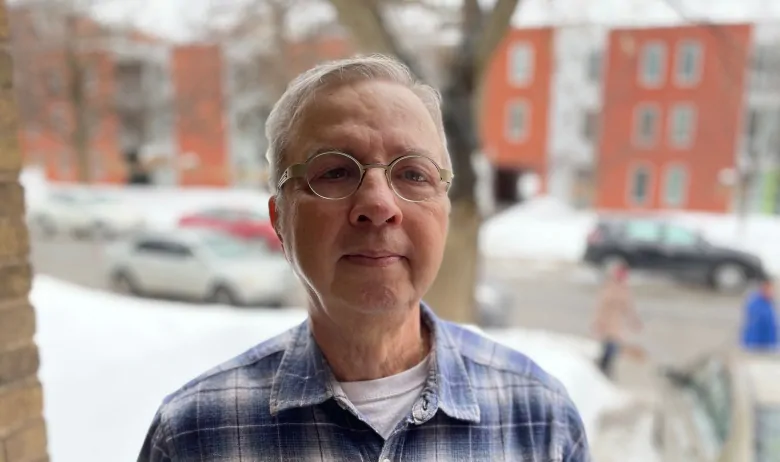

Now 81, Cowling is in palliative care at home in Westmount, a suburb west of downtown Montreal, home after having exhausted treatment options that, for all those years, helped her battle what she calls a “clever disease.”

Because of her fragile health, she’s barely been able to leave her home since the beginning of the pandemic.

The vaccines have offered the hope of getting some quality of life back, but Cowling and others in similar situations, and their advocates, say Quebec’s distribution plan isn’t equally accessible by everyone.

The province wants seniors who live at home to get vaccinated at mass centres set up across Quebec, but for Cowling the problem is simple: “I’m not allowed to go out.”

And while Ontario and British Columbia have recently announced programs to vaccinate vulnerable people in their homes, Premier François Legault hasn’t said whether Quebec would follow suit.

It’s an oversight Cowling believes the government should rectify immediately.

“What’s left of my life, I’d like to enjoy it,” she said.

Legault said on Tuesday that Quebecers born in 1936 or earlier would be able to make appointments to get vaccinated at mass vaccination centres as of next week, with younger age groups to follow as more vaccine shipments arrive.

Although appointments can be taken by phone at 1-877-644-4545, the government is strongly encouraging people to reserve their spot through an online portal at quebec.ca/covidvaccine.

Difficult to reach

David Cassidy, the past president of Seniors Action Quebec and current secretary treasurer of Gay and Grey Montreal, says there is a “groundswell of opposition” from organizations serving seniors that are calling on the government to broaden the ways it inoculates the population.

“We find [the government’s] general attitude toward seniors to be unsupportive,” Cassidy said.

Several of the mass vaccination centres are difficult to reach by public transit, Cassidy said, giving as an example Decarie Square in the community of Côte-Saint-Luc, which pedestrians must cross a highway to get to from the nearby Metro station.

“A lot of us are afraid to go outside because we don’t want to slip and fall and break our hip,” he said. “Simple mobility issues that people take for granted, for seniors it could be life and death situation.”

Gerry Lafferty, the director of the New Hope Senior Citizen’s Centre, says he’s received several calls from clients of his organization — which helps thousands of seniors dealing with isolation in western Montreal — about the vaccination campaign’s inaccessibility.

“Seniors I have spoken to have said, ‘There’s a lot more in my life behind me than what’s ahead of me, and the past 12 months have been difficult,'” Lafferty said, noting most haven’t been able to see their children and grandchildren.

“The people I’m talking to want the vaccine and want it as soon as possible, but in a safe way.”

The provincial government has hinted it would be making the vaccine accessible in pharmacies and some doctor’s offices, like it did for the influenza vaccine, but hasn’t said when. The province also hasn’t made any definite statements about in-home vaccinations.

The lack of a detailed plan has made people like Cowling feel neglected.

David Robinson is 73 and uses a respirator at home, where he takes care of his 93-year-old mother, who needs a wheelchair to move around.

Robinson lives in Inverness, a small town south of Quebec City, and says he, too, would prefer the government find a way to offer vaccination in people’s homes.

“If the [clinics] can come and get your blood test at home, they can do the same with the shot,” he said.

Robinson says he’s been coping well with the pandemic, despite harsh restrictions.

“Oh, I’m fine with it. I’m busy all the time.”

Cowling, too, has found ways to keep herself occupied, Zoom meetings and Facetime chats with family here and there.

But she can’t help but miss the real face-to-face contacts, the walks with friends around her neighbourhood, brushing a grandchild’s cheek.

“My phone is my lifeline. I talk to everybody, but I haven’t seen anybody!” she says. “When you don’t see your grandchildren for over a year, that’s a very long time.”

“You miss them in a year.”