In 1970, Jane Fonda almost quit the role for which she won her first Oscar. The character Bree Daniels, in Alan J. Pakula’s surveillance thriller Klute, was a New York City sex worker caught in the middle of a missing persons case. That spring, Fonda had spent two months on a road trip across America, where she witnessed firsthand the social and political issues that plagued the nation. She met with students at universities and soldiers at GI coffeehouses, was arrested for passing out antiwar pamphlets at army bases, and attended a speech on the women’s movement that ignited her own personal feminist revolution.

With this burgeoning mindset of political consciousness, Fonda felt conflicted about playing a sex worker in a Hollywood film. “I’d begun to wonder if it wasn’t politically incorrect to play a call girl. Would a real feminist do that? A real feminist wouldn’t have to ask herself such a question,” Fonda writes in her 2005 memoir, My Life So Far. She sought advice from her friend Barbara Dane, a singer and activist, who said: “Jane, if you think you have room in this script to create a complex, multifaceted character, you should do it. It doesn’t matter that she’s a call girl, as long as she’s real.”

Fonda rose to the occasion, taking a role that could have been reductive and exploitative, and instead making it a nuanced character that mirrored parts of her own life at a vital transitional moment in her career. She went from a Hollywood starlet playing lighthearted roles in romantic comedies like Barefoot in the Park to Barbarella sex symbol, to multilayered activist-actor using her status and privilege to enact sociopolitical change. Fonda was and continues to be a pioneer of a new kind of American celebrity. She dared to publicly protest the actions of the country she loved, to seize control of her own image, and to make political films about the issues that were important to her.

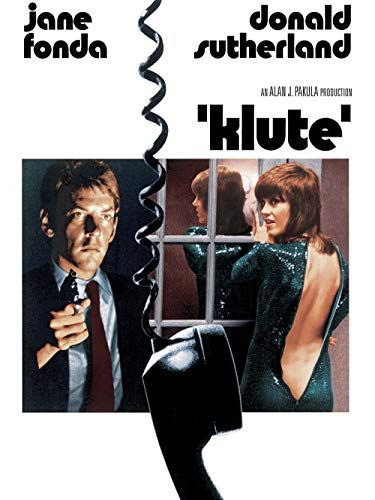

There are few people more deserving of recognition like the Golden Globes’ Cecil B. Demille Award for lifetime achievement, which Fonda will receive at this year’s ceremony. Looking back at her six-decade career, one role stands out as perhaps the genesis of her journey to becoming the icon she is today: Bree Daniels in the 1971 thriller Klute.

Going into Klute, Fonda was committed to complexity. To research the role, she spent about eight nights shadowing sex workers in Manhattan. They told her stories about all the kinds of men they’d had as clients—“senators, presidents of the biggest companies in the country, diplomats. And the more important they are, the kinkier they are,” Fonda writes in her memoir.

This content is imported from YouTube. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

She visited the morgue, to try to grasp the realities of the violence perpetrated against so many of these women. She emerged from her research still feeling that she wasn’t right for the part—even if it were a politically-sound venture, she felt that the people she’d encountered (and mainly, the men) had clocked her as a phony, just an “upper-class, privileged pretender.”

Fonda told Pakula to hire someone else for the role, but he refused. “There’s no way I would have done that picture without Jane,” the director says in Susan Lacy’s 2018 HBO documentary Jane Fonda in Five Acts. “Jane is a fascinating combination of a woman who has great courage, great strength. At the same time, [she] had been used to being—may be attracted to being controlled by somebody else. And I thought where Jane was in her life then, at a very transitional time, was absolutely right for a character of a woman who’s trying to change her life,” Pakula says.

Fonda had just starred in the 1968 sci-fi sex romp Barbarella, followed by Sydney Pollack’s Depression-era psychological drama They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, which many consider to be her first “serious” role. Where Barbarella served as a vehicle for her then-husband Roger Vadim to display Fonda as a sex symbol, her performance as Gloria in They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? highlighted the depth of her talents as a dramatic actor. She was nominated for an Oscar for her role as Gloria, and that film marked the first time she collaborated with a director on the creative direction of both her character and the film itself.

Klute solidified that transformation into prestige acting tinged with activism. She altered her appearance, literally shedding her luscious blonde Barbarella locks in favor of a brunette mullet-shag, now known as the Klute ‘do, though it was Fonda’s real haircut at the time. She decided she “wouldn’t dress for men anymore.”

Klute is the first in what many call Pakula’s “paranoia trilogy,” along with The Parallax View (1974) and All The President’s Men (1976). Klute, with its use of taped recordings of conversations as a fear device, seemed to portend the age of surveillance, pre-Watergate. As a thriller, it’s slow-moving and dark (literally, thanks to cinematographer Gordon Willis’s meticulously crafted atmosphere). Donald Sutherland plays John Klute, a private investigator sent to solve the case when his businessman friend goes missing. He meets and questions Jane Fonda’s Bree Daniels, and the two begin an affair. Though the film is called Klute, as Roger Ebert observed, it should really be called Bree, because it succeeds more as a character study of her.

Early in the film, there’s a well-known moment in which Bree performs an orgasm while having sex with a client. In the middle of it, in between cooing “Oh, my angel,” she checks her watch. It’s a brilliant sort of wink to the audience. Cut to Bree sauntering down the street, carrying a fresh bouquet of yellow flowers. When she walks up the stairs to her apartment, she’s engulfed in darkness, looking around, hyper-aware. She immediately double-locks the door behind her. These small moments, along with Bree’s sessions with her therapist which Fonda improvised, build a character that resists the trope of the sex worker “with a heart of gold.”

Fonda’s performance of Bree is layered, complex, and nuanced—she stirs interest each time she hits the screen, and the movie feels instantly emptier any moment she’s not there. Fonda had an active role in the creative decisions that made Bree a woman who can’t be relegated to caricature. Fonda suggested the therapist, who was scripted as a man, be changed to a woman because she didn’t believe Bree would open up to a man. She also asked that those scenes be shot at the end of production, so she would be more fully immersed in her character.

Bree is a sex worker, a woman seeking freedom and independence, an actress. She wants love and affection, but doesn’t know what to do with it when she feels the first inklings of a real romance with Klute. She’s paranoid and unsure, stalked by a man in the shadows—early in the film she dismisses her gut feelings as “just feelings, just me.” She’s a complex female character, a rare sight in 1971 and even today, brought uniquely alive by Fonda.

In her memoir, Fonda discusses the film’s climax, in which the terrifying businessman who has been stalking Bree plays a tape recording of her friend. “I can hear fear rising in my friend’s voice and I realize that the man sitting across from me had taped their conversation just before he murdered her and that he intends to kill me as well,” Fonda writes.

Fonda describes her genuine reaction to the scene, which plays out on camera:

“I began to cry—for all the victims… I knew when we finished the scene that my reaction would not have been the same had it not been for that cross-country trip with Elisabeth and the stirrings of a new feminist consciousness in me, locating an empathy toward women. I understood then that my expanding consciousness as an activist could broaden my understanding of people and why they behave as they do—from (rhetorical, but it’s true) a purely Freudian, individualist perspective to one that includes historical, societal, economic, and gender-based factors—and that this in turn might make me more compassionate and my acting more intelligent. Even now, when I watch Klute I admire everything about it.”

Fifty years after Klute, Fonda still leads with the crucial empathy of the activist she became in those early years of her career. With the exception of the “Hanoi Jane” photograph (which she deeply regrets), she stands by most of the work she did back then and continues it today. At 83 years old, she’s still choosing roles that shed light on issues that are important to her, like the representation of older women’s sexuality in Grace & Frankie. She’s still doing anti-racism work, fiercely supporting Indigenous initiatives, and she spearheads the environmental movement Fire Drill Fridays. To some, she remains a divisive figure; to many, she’s an icon. The beauty of Jane Fonda is that she is both those things, and much, much more.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io