As a wet winter gives way to spring, Lisbon’s Campo das Cebolas square is empty and quiet.

From the nearby ferry terminal, commuters from neighbourhoods on the other side of the Tagus river go back and forth. Between the empty, pedestrianised square and the river bank runs the Infante Dom Henrique highway, named after the discoverer, Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1960). A few hundred metres away, a soaring, empty cruise ship, the Vasco da Gama, evoking the great 15th-century explorer, is moored to the dock.

References to Portugal’s epic, seafaring past like these litter this city – there is even a Vasco da Gama shopping mall. But until now, there has never been a single explicit reference, memorial or monument in Portugal’s public space to its pioneering role in the transatlantic slave trade, nor any acknowledgement of the millions of lives that were stolen between the 15th and 19th centuries.

This is the task that has brought Kiluanji Kia Henda, Angola’s most successful contemporary artist, here from his hometown of Luanda. The forthcoming Memorial-Homage to the Victims of Slavery that he has designed will be the first memorial of its kind in Portugal and, he says, “the greatest challenge I’ve faced as an artist”.

The installation, due to be unveiled in Lisbon this spring, features a field of three-metre-high sugar canes, forged in aluminium, alluding to the cold economic rationale that drove the transatlantic-slave trade. It is also a challenge for Portugal. For a country that both established the transatlantic slave trade and was one of the last to continue reaping its profits (it was still using de-facto slave labour in its colonies in the 1960s), Portugal has been slow to reckon with its past.

The national school curriculum, museums and tourism infrastructure all amount to a grandiose rendering of the country’s 15th to 17th-century “discoveries” in Africa, Asia and the Americas, and a selective recollection of its 20th-century colonial exploits in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, São Tomé & Principe, Goa, Macau and East Timor.

There are monuments and statues up and down the country dedicated to navigators, missionary priests responsible for the conversion of Africans and Indigenous people to Catholicism, or soldiers who fought against African independence in the colonial wars. Meanwhile, it is often said that “Portugal is not a racist country”, despite enormous structural inequalities and decades of documented discrimination. “There has been a silencing here of centuries of violence and trauma,” says Kia Henda.

However, a burgeoning movement here – the Movimento Negro – along with global calls to “decolonise history”, have begun to challenge the way Portugal views itself, from past to present. The Movimento Negro has been around in various forms in Portugal since the start of the last century; the latest resurgence of it is now in its second generation. Most of the sizeable Black population in Portugal today are immigrants and their descendants from the former Portuguese African colonies, who emigrated here from the 1960s and hold in their memories and histories a very different version of Portugal’s past. Kia Henda’s memorial is seen as part of this process; erupting on the national landscape and expected to stay.

Significantly, the memorial is not an initiative of the Portuguese government, but came about in 2017, when the Djass Afro-descendent Association, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) founded by the Portuguese MP, Beatriz Gomes Dias, won a popular vote for public funds.

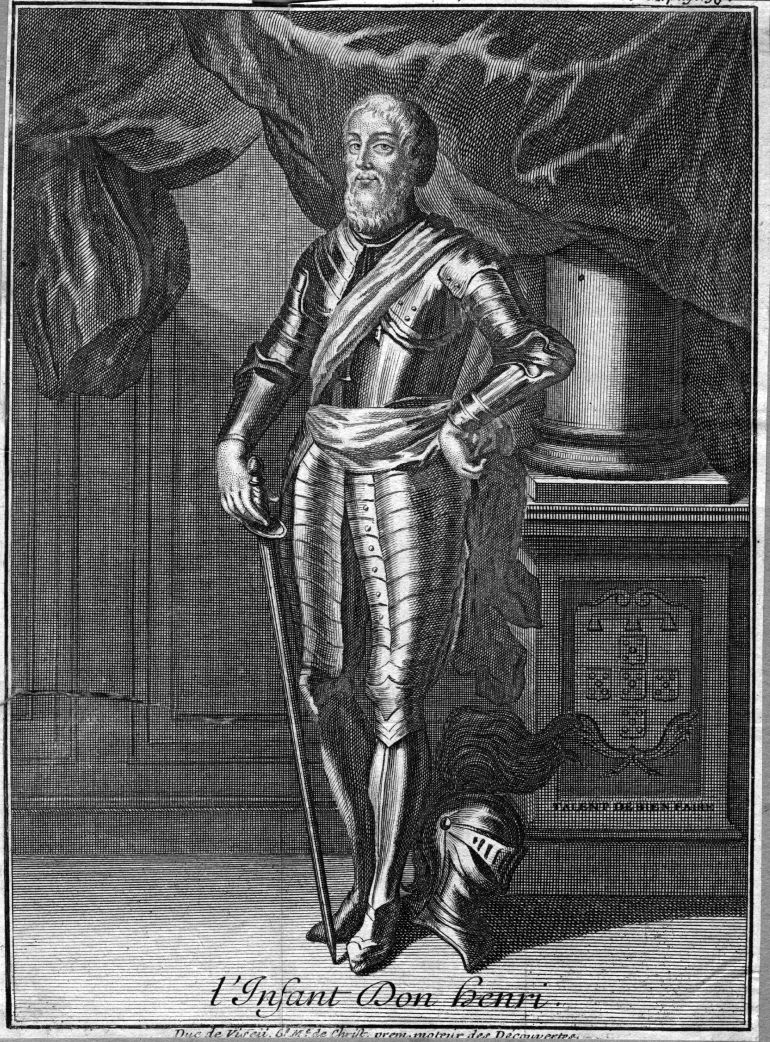

Circa 1450, Henry, known as The Navigator (1394 – 1460) the Portuguese prince, accredited with the discovery of the Madeira Islands, the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Circa 1450, Henry, known as The Navigator (1394 – 1460) the Portuguese prince, accredited with the discovery of the Madeira Islands, the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]‘A plantation in mourning’

That the memorial’s artist comes from Angola, the country that suffered the most catastrophic loss of lives during the trade in enslaved people at the hands of the Portuguese, is poignant. By the 19th century, Angola had become the largest source of enslaved people taken to the Americas. “For me, it is about building a bridge to the past as a way of establishing a dialogue about these historical cycles of violence,” says Kia Henda.

“The modern world would not exist if it was not for enslavement,” he says. “The modernity you see here was built on the backs of Black people. It’s important that there is awareness about that.”

From the mid-15th century, when explorers such as Vasco da Gama opened up new ocean routes from Europe around Africa, to Asia and to the Americas, Portugal also traded in enslaved people. Often by force, and under the banner of Christian crusading missions, the Portuguese established settlements and trading posts including, among others, in the countries, they would later claim as colonies – Angola, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Principe, Mozambique, Goa – and Brazil.

From the 16th century, the Portuguese established sugar plantations in Brazil, using enslaved labourers, shipped across the Atlantic from the West coast of Africa, to produce what was then the world’s most precious commodity. The lucrative transatlantic slave trade became an international enterprise involving all of the European colonisers, including the British, Dutch, French and Spanish. However, its starting point, both historically and geographically, was Portugal.

Lisbon main cathedral and the castle neighbourhood panorama from Campo das Cebolas square [Getty Images]

Lisbon main cathedral and the castle neighbourhood panorama from Campo das Cebolas square [Getty Images]The mini-golf course – hiding a mass grave

In the southern coastal city of Lagos, once Portugal’s second-most important harbour, the ProPuttingGarden miniature golf course serves as an uncomfortable reminder of the way this history has been glossed over.

It was here in 2009, during excavations for an underground car park, that a mass grave was uncovered containing the remains of children and adults, some with their hands bound. Forensic archeologists dated the deceased back to the 15th century, finding them to be of African descent. The remains have been kept in storage and barely mentioned since, however.

Laid out with synthetic green grass, bubbling fountains, preened shrubbery and curvaceous dancing statues, in the shadow of the old City Walls – which serve as an official historical landmark – there’s no marker official or otherwise anywhere around ProPuttingGarden to indicate the history of the site. Yet there is little doubt that the remains uncovered belong to the grim history of Portuguese slavery.

Lagos is the port where the first enslaved Africans disembarked from Portuguese ships in 1444, marking the very beginning of the transatlantic slave trade. Yet the only acknowledgement of this history within the popular, touristic centre of the city is a small museum called the “Slave Market” which opened in 2016, in collaboration with UNESCO.

“A lot of Portuguese people don’t even know that such a museum exists,” says Naky Gaglo, a historian and tour guide specialising in the 16th to 18th centuries. “The museum itself lacks a lot of information. My personal opinion is that it doesn’t change the conversation a lot.”

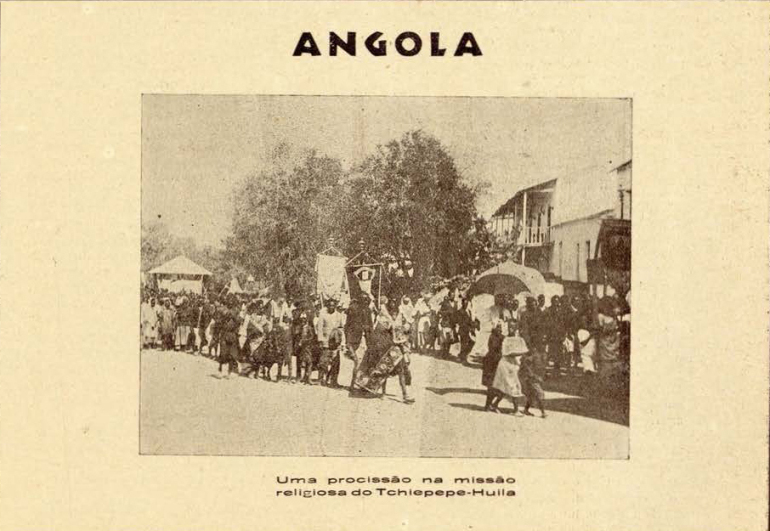

A photograph showing a religious procession in Angola, one of Portugal’s colonies, as printed in the propaganda magazine, Portugal Colonial, in 1931 [Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal]

A photograph showing a religious procession in Angola, one of Portugal’s colonies, as printed in the propaganda magazine, Portugal Colonial, in 1931 [Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal]‘A way to fill the spaces in’

Cristina Roldão is a sociologist and organiser. “Our history is full of blanks and silences,” she says. “If you grew up Black here, you will have grown up looking for ways to fill the spaces in. We are constantly having to rebuild those histories because the work of previous generations has been systematically erased and silenced. We need anchors.”

The new memorial is not only a denunciation of the crimes of the past but also points to an effort to recognise and honour those who lived through it – a history that has been much neglected.

“We must not allow ourselves to fall into historical amnesia,” says Kia Henda. Beyond the trafficking of millions of enslaved people from Africa to the Americas across the Middle Passage of the Atlantic Ocean, less attention has been paid to the thousands of Africans who were taken to Europe and stayed there, forging a much more diverse society than is often acknowledged.

Arriving from Togo six years ago, Naky Gaglo was surprised at how little Portugal’s role in the slave trade was acknowledged publicly – especially given the impact he knew it has had in countries such as his own homeland. “It’s simply not discussed in the mainstream. There is a big problem here with how history is taught in schoolbooks. So, I decided to undertake my own research, and then I ended up creating a walking tour. It’s a way of reminding people that this history of the Portuguese in relation to Africans cannot be erased.”

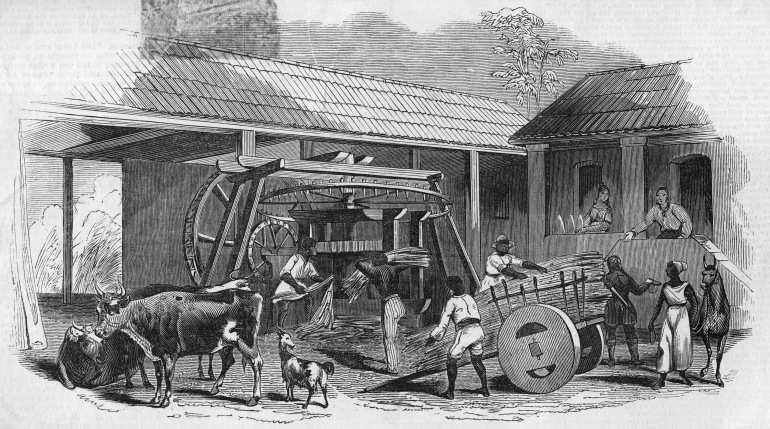

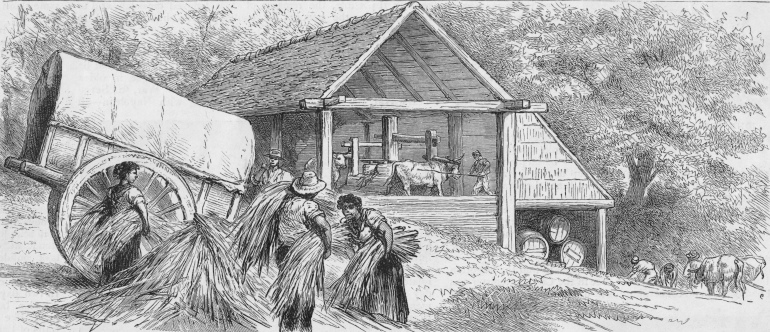

Plantation workers carry sugar cane into a mill for processing, Brazil, 1845 [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Plantation workers carry sugar cane into a mill for processing, Brazil, 1845 [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Catering to foreign tourists – mostly Brazilians, North Americans and Europeans – Gaglo’s tour begins at the centre of Lisbon’s Commerce Square, Portugal’s principal harbour from the 15th to the 19th centuries, now an iconic tourist trap.

At the edge of the square, the Lisbon Story Centre, with its room that simulates the 1755 earthquake here, and the Bacalhau cod fish history museum – neither of which makes any reference to the slave trade – are both deserted. Gaglo is standing with his back to the river, the portal for the fabulous riches that the “age of exploration” brought; among them gold, spices, sugar and people, many just children.

From here, on his tour, he begins to walk us towards the centre of the city, recalling: “In the 1400s, the Portuguese travelled to Africa and began to trade in enslaved people. As Lisbon became the epicentre of the slave trade, lots of Africans ended up living and working here, in the city, most in domestic work in the houses of the elites, and others in agriculture”.

By the mid-16th century, Africans were part of almost every area of Portuguese life, and around 10,000 Africans were living in Lisbon, making up 10 percent of the population. “It was the first European city with a large concentration of Black people,” Gaglo explains, strolling through Lisbon’s still-resplendent downtown. “Mostly life in the city for Africans was work, work, work. They were housemaids, they took care of children in the city, they provided water for the houses, the men worked unloading ships, in construction. Enslaved people were denied a family life, because mostly men and women would belong to different owners, who didn’t let them leave to get married.”

Not all of Lisbon’s African population were enslaved, Gaglo points out. “There was also an area called Mocambo where you had a number of freed or conditionally-free men and women, who had a very different life – though still, not an easy one,” he adds. Street by street, Gaglo recalls the hardships and nuances of Black life in Portugal over several centuries: “By walking a little in their footsteps, we are reminded of their suffering, and of the lives they led.”

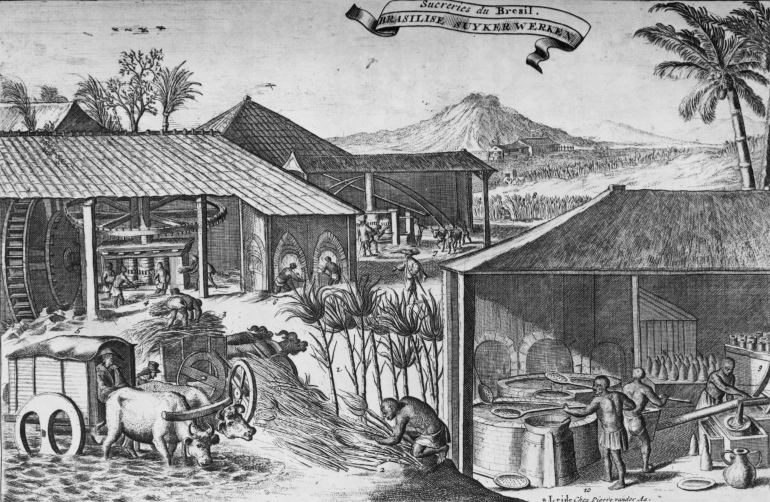

Sugar cane is processed at a factory in Brazil, circa 1700. An illustration from ‘Les Indes Orientales et Occidentales, et Autres Lieux’ by Romeyn de Hooghe [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Sugar cane is processed at a factory in Brazil, circa 1700. An illustration from ‘Les Indes Orientales et Occidentales, et Autres Lieux’ by Romeyn de Hooghe [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]Catholic brotherhoods

The city that Gaglo depicts in his tours no longer exists; it was almost entirely destroyed in the 1755 earthquake that cost around 50,000 lives. Six years later, in 1761, Portugal abolished slavery on the mainland. There are few traces of the Black presence that predated these historical watersheds in Lisbon, and many crucial archives were lost at the time. Nonetheless, Gaglo believes “there’s a lot still to be uncovered” by historians – including himself.

What role does the memorial play in this? For Gaglo: “It is just one step … We need to reach the point where we can talk about the history of slavery without fear, but that is still difficult. The curriculum, the way we talk about the past here and understand it – the whole discourse about Portuguese history – must change.”

Gaglo normally ends his tour breaking bread with his companions in a Cape Verdean restaurant – but restaurants in Lisbon are now closed for the foreseeable future. We finish, instead, in Sao Domingo’s square, long an important hub of African life in the city and the site of several Black Lives Matter protests in recent years.

At the doors to Sao Domingos church, Gaglo invokes the memories of the Black Catholic brotherhoods that played a complex and even subversive role in Portuguese society under slavery from the 16th Century. Catholic churches all over the country had cults whose members were a mixture of enslaved and free men and women, devoted to the worship of specific saints such as Our Lady of the Rosary.

The conversion of Africans to Catholicism was a pillar of slavery, and the Church encouraged the emergence of these brotherhoods – unaware that, under the guise of Catholic symbols and rituals, other Gods continued to be worshipped, as also happened in other societies of enslaved people such as Brazil and Cuba.

Crucially, however, these brotherhoods also offered a social life and support to those ostracised from society in almost every other way. “The fraternity can help you financially, with health problems, with legal assistance… they were spaces that offered protections and certain privileges to Black people,” explains Gaglo, “but we must not forget that they also sought to reinforce the domination and subjugation of Africans.”

They also became a way of resisting. The brotherhoods were among the earliest organised agitators against slavery, and would often collect funds among themselves to purchase the freedom of enslaved members.

A primitive cana mill at Castanho in Brazil, for crushing sugar cane by ox-power, circa 1800 [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

A primitive cana mill at Castanho in Brazil, for crushing sugar cane by ox-power, circa 1800 [Hulton Archive/Getty Images]The saga of Mendonça

The history of these brotherhoods is also central to the work of José Lingna Nafafé, an anthropologist and historian at the University of Bristol in the UK. Nafafé has been tracing the history of a 17th Century Angolan abolitionist who went by the Portuguese name of Lourenço da Silva Mendonça. A prince of the Kongo Kingdom of Ndongo (in modern-day Angola), Lourenço was exiled from Ndongo for declaring war on the Portuguese invaders and sent to Brazil in 1671.

As a political exile of the Portuguese crown, Mendonça lived a relatively privileged life in Bahia, the northeastern state of Brazil where the Portuguese had introduced sugar-cane plantations and brought huge numbers of enslaved Africans to work in them. But while he was there, according to Lingna Nafafé, Mendonça met the legendary Zumbi dos Palmares, a man who had escaped slavery years earlier to establish the Quilombo (free town) de Palmares, a huge Afro-Brazilian maroon community of people who had escaped slavery. It was run according to their own laws and cultural norms and took up armed resistance against the Portuguese who tried to recapture them.

“The authorities were afraid that Mendonça would run away and join Palmares,” says Nafafé, an animated storyteller – even over Zoom – his walls covered with pictures from his upcoming book on Mendonça. “So, they sent him and his family away again, this time to Portugal in 1673.”

July 12, 1975: Admiral Rosa Coutinho of the Portuguese Revolutionary Council reads out the document declaring independence for the Gulf of Guinea islands of Sao Tome and Principe, from Portuguese rule [Keystone/Getty Images]

July 12, 1975: Admiral Rosa Coutinho of the Portuguese Revolutionary Council reads out the document declaring independence for the Gulf of Guinea islands of Sao Tome and Principe, from Portuguese rule [Keystone/Getty Images]

If the move was intended to subdue Mendonça’s anti-Portuguese activities, it failed. It was in Europe that Mendonça was to make his mark as an abolitionist – a trajectory that Nafafé has painstakingly pieced together from documents found in dusty archives across the continent.

After several years of study at a monastery in Portugal, Mendoça was appointed as an advocate of the Black Brotherhoods. This, according to Nafafé, is when records show that he had begun to work on a petition against slavery. Using his position, he enlisted the support of Black Brotherhoods across the Iberian peninsula, who lobbied the Vatican by writing letters that urged Pope Innocent XI to abolish slavery across the Atlantic. Pope Innocent XI, who held the title from 1676 to 1689, did, indeed, condemn the slave trade. With power in Europe divided at the time between the Crown and the Church, the Vatican had enormous power and influence over the fate of the enslaved.

“It has never previously been established by historians that Mendonça was an African, which is really incredible – that in the 1600s you had this African man who travelled all over Europe to mobilise an activist movement for the liberation not only of Black Africans, but also of Indigenous people in the Americas,” says Nafafé.

In 1684, Mendonça went to the Vatican, where he accused the nations involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade of crimes against humanity. “What I’ve discovered is that this wasn’t just a petition, it was actually a court case, undertaken by Black Africans and supported through highly organised international solidarity,” explains Nafafé. “People always think that the legal abolitionist movement started in Britain, in the late 18th century, but Mendonça really forces us to review our positions on this.”

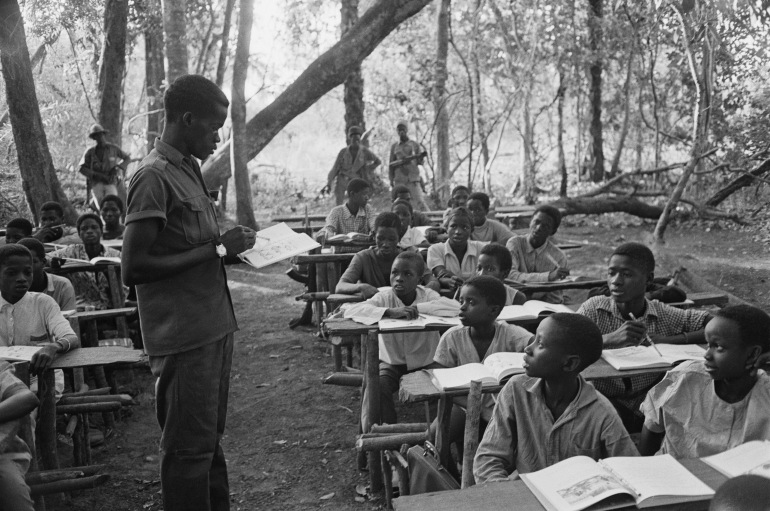

A teacher talks to his pupils at a guarded outdoor classroom during the Portuguese Colonial War, Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, 1972 [Reg Lancaster/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

A teacher talks to his pupils at a guarded outdoor classroom during the Portuguese Colonial War, Guinea-Bissau, West Africa, 1972 [Reg Lancaster/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]Protagonists of their own stories

Originally from the former Portuguese colony of Guinea Bissau and one of only a handful of African scholars working on early modern history, Nafafé’s findings seem to reinforce calls to “decolonise history”, and for new perspectives to be shone on old stories.

“I’d like to think that future generations of 16-year-olds, looking in the library to learn about their history, could find some positive references,” says Cristina Roldão, who also feels there is much work to be done on the way Africans and Afro-descendent people have been portrayed in Portuguese history. “Not just that they might be the descendants of slaves, of people who were colonised, or stories about people living in impoverished neighbourhoods – but that they might encounter a different kind of narrative, in which Black people are the protagonists of their own stories, where we talk about how they lived and resisted. This is important to the Black population today – but it’s just as important for everyone else in Portugal that the truth and complexity of this history is restored.”

Circa 1950: A water carrier, with a baby on her back, at Praia, in the Cape Verde Islands [Keystone/Getty Images]

Circa 1950: A water carrier, with a baby on her back, at Praia, in the Cape Verde Islands [Keystone/Getty Images]

Roldão herself has recently started researching the histories of Black women in Portugal since the 16th century: “I felt drawn to these stories,” she says. “I wanted to know what these women’s lives were like; who were they? I love to imagine where they met, what they talked about … I want to uncover a history that is shrouded in silence.”

Roldão’s research weaves the threads between the lives of washerwomen and street food sellers, to the “Kongo Queens” – a ceremonial position within the Black Catholic brotherhoods, appointed and crowned each year during festivities.

“There was a whole complexity of women’s lives within the society of slavery that is never talked about,” she says. “Around 1700, for example, there’s a letter written by Black women hawkers who sold their goods on the steps of a hospital, complaining about being mistreated by the local police, and they say that they have a right to be there because that’s where they have always been since time immemorial. To see that document in the flesh, for me, as a post-colonial child, is just… awesome. Or, for example, when you start looking into the ceremonial queens of Kongo, for example, you find them in Brazil and in other Latin American countries too, in the [African] diaspora. That search, for Black history in the feminine, is not just interesting, it’s … delicious.”

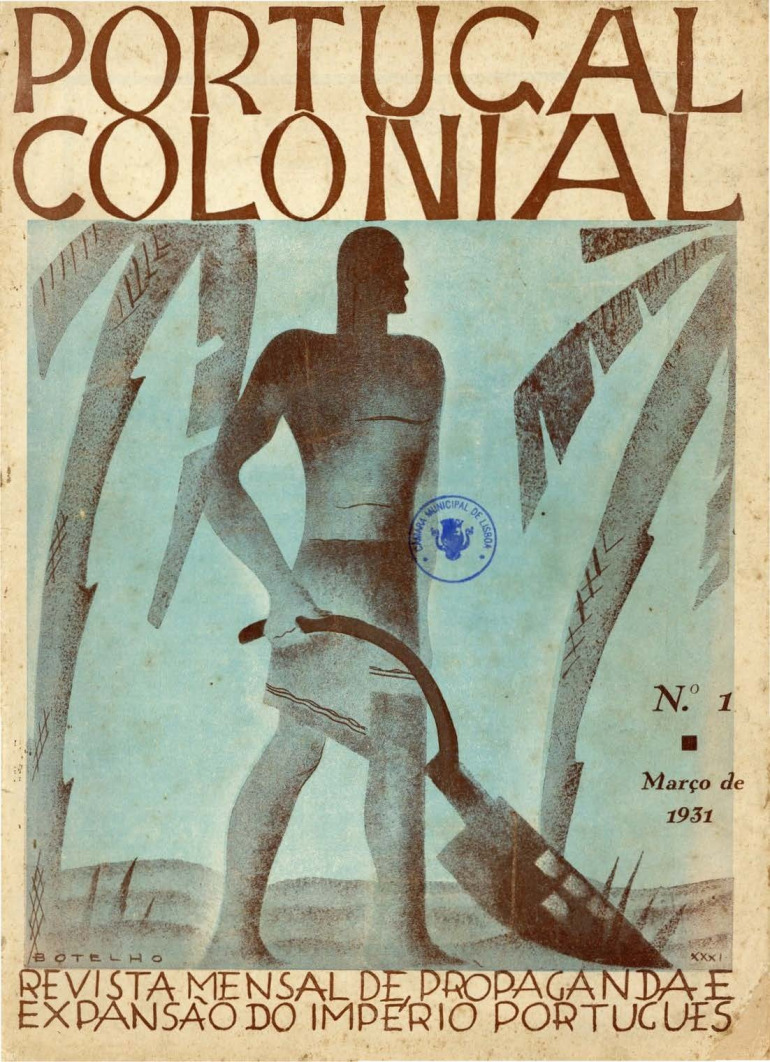

The front cover of a 1931 monthly propaganda magazine heralding the virtues of Portugal’s colonies, produced by the Portugal Colonial company and edited by Henrique Galvão. Galvão went on to become a major opponent of Portugal’s dictatorship and an outspoken critic of violence in the colonies [Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal]

The front cover of a 1931 monthly propaganda magazine heralding the virtues of Portugal’s colonies, produced by the Portugal Colonial company and edited by Henrique Galvão. Galvão went on to become a major opponent of Portugal’s dictatorship and an outspoken critic of violence in the colonies [Courtesy of Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal]Challenging questions for Portugal today

Roldão has worked both in and on education; she lectures at a university, and in the past has led research which shows that school pupils of African heritage in Portugal are more likely to fail academic years, to drop out of school, and are more often pushed towards vocational courses than into higher education.

She is also a vociferous participant in the campaign to get the Portuguese state to collect data on race and ethnicity – which is illegal, under the current Portuguese Constitution.

Intended to make amends for the explicit racism of the Portuguese colonial dictatorship that was overthrown in 1974, this clause in the constitution has become a major sticking point for anti-racism movements in Portugal because it means there is no information about population numbers for ethnic minorities at all in Portugal. The absence of data has made it hard for activists to make a case for more investment in public services for Afro-descendent and other racialised communities, or to prove the existence of the racial bias and structural inequality, for which there is plenty of anecdotal evidence.

Like her previous academic and activist work, Roldão’s historical research also seeks to pose serious and challenging questions within Portugal. “I see no contradiction between looking into statistical data on inequality in the education system – and thinking about the problems with the national school curriculum and the absence of histories – and how in turn this relates to the kinds of jobs that our parents have in Portuguese society,” she says. “They are linked to the issue of colonial slavery – so, for me, it is all continuous and interconnected.”

The Padrao dos Descobrimentos, a 1960s monument to the Portuguese discoveries by the Tagus river in Lisbon [Armando Franca/AP Photo]

The Padrao dos Descobrimentos, a 1960s monument to the Portuguese discoveries by the Tagus river in Lisbon [Armando Franca/AP Photo]

In making these connections, however, Roldão is touching upon one of the most contentious issues in Portugal today. The 16th century is the period Portugal is most proud of, an era known as “the age of the discoveries” that saw the country’s ascension as a global imperial power of fabulous wealth and a certain kind of cosmopolitanism. The epic, almost mythological way this history has been commemorated has made it a cornerstone of Portuguese national identity, as well as an important element in how it is marketed as a tourist destination – “Historical Lisbon, Global City”, as its application for UNESCO heritage status reads. And, in 2017 – the same year that the slavery memorial was first proposed by activists – Lisbon’s local council revealed its own plans for a “Museum of the Discoveries” along the same riverside.

Seeming to amplify the contested representations of this particular period – at a time when many are calling for them to be revised – the idea of a new Museum of the Discoveries, and in particular its name, has generated a national controversy that has divided historians and public opinion.

Critics say the way this history is still remembered in terms of “discoveries” and “encounters” with other cultures occludes the violence and brutality that the Portuguese inflicted to achieve the domination of their trading posts and colonies. “What you can tell from the case of the Museum of the Discoveries, is that the national narrative is still all about the influence that Portugal once had in the world,” says Marcos Cardão, a historian of Portuguese popular culture and identity.

These well-established renderings of Portuguese history are perhaps best encapsulated by the cluster of tourist attractions located just a few kilometres down-river from Campo das Cebolas, in Belém, which hark back to the 16th century. There is the Torre de Belem fortress; the Jerónimos monastery, which contains the tomb of Vasco da Gama – the celebrated navigator who charted the maritime route around Africa to India; and, perhaps most recognisable of all, the Monument to the Discoveries statue, and its panoply of oversized explorers, bards and missionary priests.

Unbeknownst to the tens of thousands of sightseers who come here every year, however, and carefully disguised in the wording of its visitors’ centre exhibits, this memorial is the product of a much later period in Portugal’s history, an invention of the nationalist dictatorship that ruled Portugal and its colonies from 1926 to 1974.

Jeronimos Monastery is seen on December 23, 2013 in Lisbon, Portugal. The monastery is one of the most prominent monuments of the Manueline-style architecture (Portuguese late-Gothic) in Lisbon, classified in 1983 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the nearby Tower of Belém [Pedro Loureiro/Getty Images]

Jeronimos Monastery is seen on December 23, 2013 in Lisbon, Portugal. The monastery is one of the most prominent monuments of the Manueline-style architecture (Portuguese late-Gothic) in Lisbon, classified in 1983 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with the nearby Tower of Belém [Pedro Loureiro/Getty Images]The fascist origins of the ‘discoveries’ narrative

The Monument to the Discoveries was originally created as a temporary statue made of fibrous plaster for the 1940 Portuguese World Exhibition, an ostentatious act of propaganda that took place at the height of dictator António Salazar’s oppressive Estado Novo regime (1932 to 1968), during a period marked by poverty and austerity.

By this point, Portugal had imposed colonial rule on Angola, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Sao Tomé and Cape Verde, as well as continuing to assert its claims over Macau, Goa and East Timor in Asia (though having lost its hold on Brazil in 1825). The racist ideology that underpinned Portuguese colonialism had been encapsulated in an earlier public fair, the Portuguese Colonial Exhibition, held in the city of Porto a few years prior.

The 1940 World Exhibition in Lisbon, meanwhile, was designed to forge a new sense of national identity that reflected Salazar’s imperial ambitions – “the very synthesis of our glorious history”, according to a guidebook to the exhibition – promoting Portugal’s achievements in the world past and present, and binding them together, forever. “These official commemorations turned the Portuguese colonial experience into a sort of civil religion,” says Cardao.

To this end, the exhibition resurrected the symbols of Portugal’s Age of Discoveries along the banks of the Tagus river in Belem, where huge swathes of housing and industry had been displaced for the event. As well as giant statues of the explorers and their patron, Henry the Navigator, there was a replica 16th-century caravel ship and long parades of marching groups in costume, who carried flags of the military Order of Christ (the flag of the 16th-century Christian crusaders) and performed acrobatics for the dictator, Salazar, and his entourage of Catholic priests at the opening ceremony.

The exhibition encapsulated everything that Salazar wished Portugal to be known for – for having “discovered” India, Africa and the Americas, and for bringing Christianity and “civilisation” with them; there was no place in this narrative for the violent realities of slavery or colonisation. “As well as being based on possession, imperialism and civilising missions, these narratives were also very ethno-centric,” Cardão says, “fetishising and exoticising Africans, for example.”

Portuguese dictator Antonio De Oliveira Salazar (1889 – 1970) reviews troops about to embark for the African colonies of the Portuguese Republic, circa 1950 [Evans/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

Portuguese dictator Antonio De Oliveira Salazar (1889 – 1970) reviews troops about to embark for the African colonies of the Portuguese Republic, circa 1950 [Evans/Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images]

While the exhibition – and the temporary monument – lasted only a few months, the ideas they perpetuated were hugely popular and deeply influential. “The idea of the Portuguese as exceptional colonisers became a way of narrating history and imagining Portugal and the Portuguese people,” says Cardão. “Yet, by seeking to point out their exceptionalism, and how different they were, they were simply replicating what all of the other European colonisers did.”

The Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre encouraged these ideas in 1952 when he coined the term “Luso-tropicalism (“Luso” refers to Portuguese and originates with the Lusitanian people who were among the early native inhabitants of the Iberian peninsula). “Freyre’s theory was that Portuguese colonialism was exceptional, because they were more humane, more fraternal than, say, the British or the Belgians, who were understood as being more brutal and less tolerant of other races,” says Cardão.

It was a useful framework for a regime that intended to export thousands of (mostly poor, rural) Portuguese to its colonies, as Cardão explains: “Luso-tropicalism became the common rhetoric of the regime … promoting the idea that the Portuguese empire was a single political unit, spread across the continents, and multi-racial, with a kind of easy co-existence of different peoples and cultures, in absence of racial prejudice.”

Life in the colonies, however, was far from the “racial democracy” that Freyre romanticised. Under the legal framework of the Estatuto do Indigena – or Native Statute – Indigenous subjects of Portuguese rule had an inferior status to white Portuguese, based on the explicit understanding that they were less civilised than their colonial masters. The only way for non-whites to gain access to education and other privileges in the colonies was by renouncing their own cultures to assume Catholicism, the Portuguese language and customs, and achieving the status of being “assimilated”.

Exploitation and extensive forced labour in the colonies were well documented, yet Luso-tropicalist ideas about the Portuguese people’s lack of racial prejudice remained central to Portuguese national identity and history-telling.

The 15th Century Portuguese explorer, Vasco de Gama, who is still revered as a major figure from Portugal’s “age of discoveries” [Keystone/Getty Images]

The 15th Century Portuguese explorer, Vasco de Gama, who is still revered as a major figure from Portugal’s “age of discoveries” [Keystone/Getty Images]

“The Portuguese regime actively appropriated and worked these narratives,” says Cardão. As other European powers conceded independence to their colonies, Portugal resisted calls to decolonise, even in the face of mounting international pressure as the years went on: “This is the context in which Salazar ordered the Monument to the Discoveries to be built again.”

In 1960, just as African independence movement leaders like Amilcar Cabral in Guinea Bissau and Agostinho Neto in Angola were taking up arms against Portuguese colonialism, a larger and sturdier version of the Monument to the Discoveries took its permanent place on the Lisbon riverfront. At its feet is the Compass Rose (Rosa dos Ventos), the world’s largest mosaic map – a gift from the apartheid regime of South Africa to the Portuguese dictatorship.

For Cardão, “the slavery memorial will finally bring a visual counter-narrative of this history to the city… The dominant narrative associated with these national representations of Portugal – that is, the supposed lack of racial prejudice in the “tolerant” Portuguese and the absence of racism as a result – doesn’t fly anymore. And it was the plans for the Memorial and the organising of the Black movement that has brought this change about.”

Portugal’s ever-more assertive and politically engaged Black population, now second-generation, are at the forefront of those in Portuguese society pushing for a more nuanced and complicated version of history to finally be told. This Movimento Negro has also brought more attention to the ongoing legacies of structural racism – in terms of police brutality, equal access to housing and education, and representation, for example.

The debates sparked by the Rhodes Must Fall movement in South Africa have also been felt in Portugal, with protestors targeting a statue of Padre Antonio Vieira, the 17th century missionary Jesuit priest, in Lisbon. An open letter on the issue from four Portuguese academics to the Portuguese Publico newspaper stated in February 2020: “The consensus around the narrative on the meaning and legacies of Portuguese colonialism has run dry.”

A Black Lives Matter protest in Lisbon, Portugal on June 6, 2020, following the death of George Floyd in the US [MANUEL DE ALMEIDA/EPA-EFE]

A Black Lives Matter protest in Lisbon, Portugal on June 6, 2020, following the death of George Floyd in the US [MANUEL DE ALMEIDA/EPA-EFE]

There are other challenges afoot, however. The growth of a new, far-right party, Chega, has highlighted the enduring appeal of Luso-tropicalist ideas – the party even held a “Portugal is not a racist country” protest in August 2020, in response to a national Black Lives Matter demonstration. In February 2021, a petition circulated online gathered 15,000 signatures calling for the deportation from Portugal of one the country’s most prominent anti-racist organisers, Mamadou Ba, on the grounds that “he doesn’t agree with our cultures and values”.

Nonetheless, when the new memorial takes its place on Campo das Cebolas this spring, it will mark an unsettled history with a permanent fixture on the city landscape. “It’s been a long time coming,” says Kia Henda.

Initiated by Black Portuguese, voted for by the public and conceptualised by an African artist, the memorial challenges not only the way this history has, until now, been recorded and memorialised in Portugal, but also who gets to tell it. “The new memorial will not solve everything, but I think it could be an anchor,” says Cristina Roldao, “for different memories and narratives.”