Timmy Johnson, a 23-year-old dock worker for Amazon, was skeptical when he first heard about the push to form a union at his warehouse. Scanning boxes and taking them to trucks was exhausting, but $15.55 an hour was more than he had earned as a stacker at Lowe’s, and he didn’t see the point of paying nearly $500 a year in dues.

Then he spoke to his father, a former coal miner.

“He said it was a good thing for us to have,” Johnson said. “He told me my job would be secure and they wouldn’t be able to fire me for no reason.”

So Johnson voted to unionize Amazon’s vast 855,000-square-foot warehouse in this predominantly Black blue-collar city about 15 miles southwest of Birmingham, Ala. In doing so, he joined the largest band of American workers to challenge the powerful, multinational retail company since it was founded more than a quarter of a century ago.

Congressional delegate Andy Levin (MI, D), left, visits the Amazon Fulfillment Center after meeting with workers and organizers involved in the Amazon BHM1 facility unionization effort in Birmingham, Alabama.

(Megan Varner / Getty Images)

A victory for the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union is not assured: More than 5,800 workers have the opportunity to vote. And after Amazon hired an aggressive union-busting firm, some workers say they are undecided or already have voted no.

But the union has cleared a major hurdle in getting more than 2,000 workers to sign cards supporting a union election — more than any other Amazon workplace in the country. Last weekend, President Biden delivered a major boost when he gave workers in Alabama a shout-out and stressed unions’ historic role in building the middle class.

“Unions put power in the hands of workers,” Biden said in a video message. “They give you a stronger voice, for your health, your safety, higher wage, protections from racial discrimination and sexual harassment. Unions lift up workers, both union and non-union, but especially Black and brown workers.”

Alabama may seem an unlikely place for workers to take on the trillion-dollar company founded by Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world. A conservative “right-to-work” state where workers do not have to pay dues to unions that represent them, it is home to the world’s only unionized Mercedes-Benz plant. But the Birmingham metro area was once the largest iron and steel producer in the Southeast, and it has a strong and distinct legacy of workers coming together to improve job conditions.

“When Amazon and Jeff Bezos looked at Bessemer, they saw one of the poorest cities in the state of Alabama,” said Michael Foster, 41, a lead organizer for RWDSU. “What they failed to uncover is that this was a union city of steelworkers and coal mine workers. … These people know about unions, even though this is a red state.”

If a majority of Amazon’s workers in Bessemer vote to form the company’s first labor union in the U.S. before the March 29 deadline, it would be a major setback for the company, which has seen record profits and hired more than 500,000 workers during the pandemic. A victory in Alabama could inspire a rush of organizing in Amazon warehouses across the nation — including states that are more union-friendly, such as California, Michigan and New York.

“Nobody thought we would get this far. We had people tell us we were crazy, just going up against Amazon, period,” Foster said. “Amazon is a powerful beast right now and only getting more powerful. If we don’t fight back, we’re going to be swallowed up.”

The move to set up a union began just months after Amazon opened its Bessemer warehouse last March.

Amazon worker Darryl Richardson says the pace of his job leaves him sore and weary.

(Jenny jarvie / Los Angeles Times)

Darryl Richardson, 51, was excited when he got hired at Amazon after losing his unionized job at an auto parts supplier. But as he scrambled to work as a picker, pulling hundreds of items out of large metal bins that robots brought to him and putting them in totes on a fast-moving conveyor belt, it did not take him long to decide they needed a union.

“It’s very stressful,” he said. “You ain’t got time to breathe, ain’t got time to stop. You be hoping you could catch up and a robot pause, so you can take a deep breath. But the robots don’t stop.”

His shoulders ached. His hands cramped up. Working from 7:15 a.m. to 5:45 p.m., with few breaks, he began to feel like a robot.

After eight months, he is paid $15.55 an hour — substantially lower than the $23.58 he earned at his last job.

“It’s kind of sad to work for the richest man in the United States of America and he don’t want to pay his employees fairly for what they do,” he said. “I don’t understand how a person can be so greedy.”

After seeing coworkers terminated for not keeping up with Amazon’s relentless productivity demands or leaving their station too often to go to the bathroom, Richardson clicked on the RWDSU website, filled out a form and asked: “Who do I talk to about union organizing?”

For RWDSU, the stakes are higher than just one warehouse or one company.

A pro-union sign outside Bessemer’s Amazon Fulfillment Center.

(Jenny jarvie / Los Angeles Times)

“We are concerned that Amazon is setting the model for the future,” said Stuart Appelbaum, president of the union, which has played a key role in organizing poultry workers in Alabama. “This is really about the future of work. People are managed by an algorithm. They’re disciplined by an app on their phone. And they’re fired by text message. People have had enough.

“This is as much of a civil rights struggle as it is a labor struggle,” he added, noting that Amazon’s Bessemer workforce was about 80% Black.

Amazon declined requests for interviews with company leaders.

“We don’t believe the RWDSU represents the majority of our employees’ views,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “Our employees choose to work at Amazon because we offer some of the best jobs available everywhere we hire, and we encourage anyone to compare our total compensation package, health benefits, and workplace environment to any other company with similar jobs.”

On its anti-union website, the company touts “high” wages (starting pay is about $15 an hour, more than twice the federal minimum wage) and healthcare benefits. It also warns workers that paying union dues will prevent them from buying dinner, gifts and school supplies, even though union dues are not mandatory in Alabama.

Workers who were union members in 2020 had median weekly earnings of about $1,144, compared to $958 for their non-union peers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

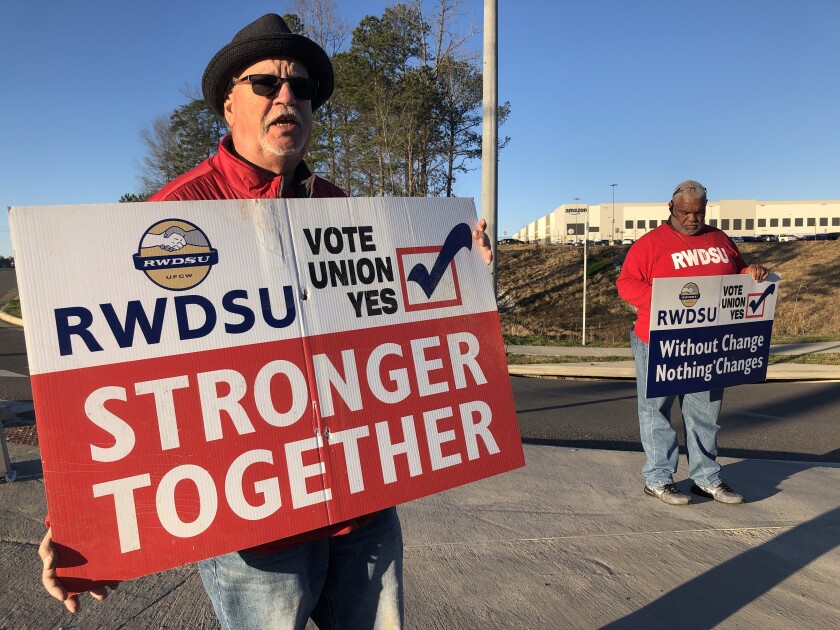

At the warehouse, tensions are high as union activists stand outside the sprawling facility every day, wielding placards that say “Stronger Together.” Inside, Amazon bombards workers with anti-union texts and signs saying “Where will your dues go?” Before voting started, the company required workers to attend anti-union “informational” meetings.

One manager last week questioned the work ethic of those pushing for a union.

“Some people just have a hard time keeping up,” said Lynn Bray Jr., 36, a project manager and floor supervisor who started out as a floor tech. “My thing is, if you work hard, somebody will see you, and at some point, you’ll definitely get an advancement.”

Some workers are tired of the barrages of messages — not just from Amazon but also RWDSU.

“This union stuff getting on my nerves,” one worker posted on Facebook, noting that she planned to send in a blank ballot. “Let it be March 30th already!!!”

“I swear!” a friend responded. “Dude walked up to my car, I mouthed ‘I’m good.’”

It is not Bessemer’s first high-stakes union battle. In the 1930s, thousands of workers walked off the job at the city’s largest iron and steel companies, demanding union recognition and higher pay, according to Robin D.G. Kelley, a professor of history at UCLA and author of “Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression.” The governor called in the National Guard after gun battles erupted between workers and company police. At least two strikebreakers were killed.

While many unions were segregated across the Deep South, Black workers held most middle- and low-level leadership positions in the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers in Bessemer. According to Kelley, “the prevalence of Black workers and the union’s egalitarian goals gave the movement an air of civil rights activism.”

Nearly a century later, the region’s industrial power and its union membership have dwindled, and Bessemer is a struggling city with a median household income of just $32,301. Workers’ opinions of Amazon are mixed. While some workers have a family history of union membership, RWDSU leaders worry that many have been swayed by the company’s union-busting messaging.

On his breaks, Richardson tries to reach out to younger workers, who he says do not understand what unions can do.

“I tell them, ‘We got to stick together, cause they’re treating us wrong and they’re firing you for no reason,’” he said. “Just think about it like this: If the union was so bad, why is the company doing everything it can to keep it out of here?”

Jasmine Thomas, 30, an order packer from Birmingham, was still undecided as she left the warehouse one afternoon last week. Although the work was strenuous and fast-paced, she said, she earned $5 an hour more than at her last job at Walmart, and she hoped to move up in the company.

“I’m still half and half,” she said. “I feel pretty comfortable as I can just go up and talk to my manager anytime I want. Everybody’s like, the union can get more for us, but what do we not already have?”

Union officials Randy Hadley, left, and Curtis Gray carry signs outside the Bessemer, Ala., Amazon warehouse.

(Jenny jarvie / Los Angeles Times)

Some workers said they had already voted against the union.

Lester Charles Samuel, 18, a stower, voted against the union last week, because his experience at the warehouse had been positive and he was making $15.30 an hour — nearly double the $8 he earned at his last job at a university cafeteria.

“I don’t have to overwork myself or strain my back,” he said. “I feel we don’t need a union.”

Brittainy Harlins, 34, also a stower, said her experience with unions in her last job as a team leader at an automotive parts supplier in Tuscaloosa was not positive.

“It’s pretty much me paying my money for them to go on vacation — that’s how I feel,” she said as she stopped at a gas station before her night shift. “Like, I didn’t see a difference with my union rep going in there with me, versus me going in there by myself.”

But Catherine Highsmith, 24, a worker who recently landed an unpaid “promotion” as a troubleshooter on the robotics floor, rejected coworkers’ arguments that they would be better off without a union.

As much as she liked her job, she wanted to know that, if she had a serious problem, a union would back her and put pressure on Amazon.

“Listen to what they’re saying,” she said of coworkers who questioned the union. “It’s me, me, me. I, I, I. The culture at Amazon is hyper-individualistic. … They want you to think about yourself and yourself only. That’s why they hate the union so much. They don’t want people thinking of themselves as a whole unit together.”