The game “What Comes After” opens with a relatable nightmare. Vivi, wearing a face mask on the subway, is overly exhausted and stressed about the very thought of going home to another evening of absolutely nothing, presumably in our present-day pandemic. She doesn’t go home, however. She falls asleep on mass transit.

This is hellish.

No wonder Vivi is relieved, upon waking, to find out that she may in fact be dead and is now surrounded by ghosts — some human, some cats and some plants. If this is the afterlife, she muses, she’s pretty lucky. “I didn’t feel pain. It cost me nothing. And I’ve been considering it for a while, anyway. You won the jackpot, Vivi!”

‘What Comes After” deals with a number of sensitive topics, and the game comes with a warning as it’s booted up. But while the interactive work grapples with self-harm, self-hate and a general lack of belief for better days, I found it to be a delightfully charming experience, a fanciful “A Christmas Carol”-like story about the importance of living.

Throughout, “What Comes After” theorizes on how the nine lives of cats actually work, what flowers want out of life and how our own worst enemy can be our mind and the places it leads us to when it is left in a neutral state. I also appreciated the writing, giving us a main character whose first thought upon potentially being deceased (she’s not) is what dying would do her to bank account.

When I completed the game, I wanted to run outside of my downtown L.A. apartment to hug strangers, feed every stray cat, water every plant and just embrace the world. But this is a pandemic, and I’ve had a hard time doing anything but being angry at the universe. Also, there’s strictly no hugging anyone these days, especially strangers. Yet playing the game — and others such as “I Am Dead,” “Spiritfarer,” “Necrobarista,” “Before I Forget” and “When the Past Was Around”— felt like a revelation, the sort of therapeutic reminders I’ve needed on how to find meaning in the day to day.

In 2020, I simply couldn’t get enough of games about death.

“I Am Dead” is a charming look at a life well-lived, even if it takes a dog to show the main character that he was celebrated and loved.

(Hollow Pounds / Annapurna Interactive)

Death, of course, is integral to almost all games. It’s a fail state that’s used to teach and has given us such parlance as “extra lives.” But death is often abstracted — bodies disappear, we get another chance, Mario goofily slides off the screen and in competitive games we rack up deaths as points. I’ve always seen this as an unintentional metaphor for how most of us generally think about death. It happens, it stinks, but let’s move on and put it behind us and not really analyze how it has changed us. For decades, games have made winning the act of avoiding death.

Games, after all, kill us relentlessly, but what struck me about the games mentioned here as well as others is how death is reframed to think about life. Even the critically adored hack-and-slash game “Hades” uses death in inventive ways.

We die often in this action game exploring Greek mythology. It’s embedded into the design of the genre the game belongs to, but death in “Hades” becomes less a point of frustration and more as a way to go back to the start and get to know the Greek mythological characters. “Hades” (PC, Mac, Switch) even reminded me of my family’s wakes, in that it wasn’t until a relative died that I learned, say, what they studied in college.

I found these games more than simply interesting or unique in their approach. I found them vital and downright healing in our pandemic year, when a state’s daily death toll gets posted on social media.

While my fragile mental state long ago meant I shut off the 10 hours of NPR that ran in the background while I worked, difficult news still surrounds. Even amid scenes of the first healthcare workers receiving COVID-19 vaccines, each day brings increased infection rates, a rising death tally and the general sense that maybe we, the Americans who have yet been untouched by the path of the virus, are becoming too numb to its life-destroying ways. Death, of course, is inevitable, but that doesn’t mean we have to dare it to come after us by not wearing a face mask.

Games, however, even the most serious of them, often have an air of whimsy. We lean into them. We don’t just play games; we perform with them.

We puppeteer characters, steer conversations and feel as if we are communicating with media rather than consuming it. The world when drawn, as fans of thoughtful animation are well aware, simply has an imaginative air about it. When I steered characters to confront death, I didn’t find funerals and tears. I found, especially in works like “I Am Dead” and “Spiritfarer,” life lessons — the danger and waste of our often selfish tendencies, and the miscommunication that too often occurs when we begin to devalue ourselves.

In “Spiritfarer,” little tasks — fishing and making a boat look nicer — add up to large acts of care, showing us that a meaningful life is one of compassion.

(Thunder Lotus Games)

I’m thinking of a small moment in “Spiritfarer” (PC, Mac, major consoles), a slow-paced game that has us tending to the needs of the dead and concerns of theirs that went unmet while they lived. In the afterlife here, we take on the persona of animals, and our deer friend Gwen remains haunted in death by her relationship with her father. We meet him too and see him cavorting, even when dead, among his mansion with his now meaningless collection of artifacts. His wealth accumulation has no power in the afterlife, but he still can’t see how a bitter obsession with stuff drove his daughter away.

This story reveals itself over multiple hours, as we construct a boat, go fishing and meet all sorts of mystical creatures who want our help. The family drama of Gwen is in the background, told through exploration and our desire to dig into it and take the time to talk to her father. The game doesn’t confront us with horror stories; “Spiritfarer” simply reminds us what it means to care for others and how we won’t succeed in doing so unless we also care for ourselves.

“Before I Forget” is a patient exploration into the mind of someone losing theirs, a look at the effects of dementia. And yet, “Before I Forget” (PC, Mac) isn’t about the terror of illness. A cozy home becomes abstract, and family artifacts remind us of singular moments or allow us to imagine others. Walls drift away from us, music embraces us and what we discover isn’t pain but a life of wonder and the sense of accomplishment one can feel when embracing all it has to offer, good and bad.

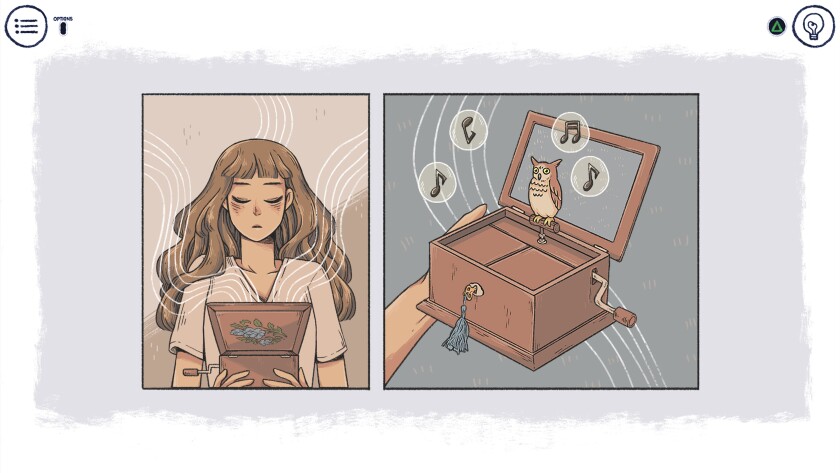

“When the Past Was Around” goes a more puzzle-like route. We see places and scenes that mattered to Eda and her late partner. A shared love of music connected them, and we look for items such as the missing pieces of a music box to get an intimate look at their loves. Sometimes it’s mundane, such as the connections forged in a laundry room, but none of these games are about big plot-defining moments because life isn’t.

The objects we share and save become puzzles that offer a look into our lives in “When the Past Was Around.”

(Chorus Worldwide)

In “When the Past Was Around” (PC, Mac, major consoles) Eda is trying to find a balance between moving on and holding on, using sometimes abstract puzzles to highlight the tension in connection.

We’re all looking for a partner who fits us like a jigsaw piece. Or maybe not. The absolute joy of “I Am Dead” is that it explores how a life’s passion doesn’t always have to be the romantic. We play as Morris Lupton, a small-town museum curator who died at 62. Amid the game’s shapeshifting watercolor art, we explore the minds of the living to learn about the ghosts that helped inform Lupton’s home city and his life.

“I Am Dead” (PC, Switch) is full of oddities — a yoga studio in a lighthouse, talking fish people, a museum exhibit dedicated to a neighborhood cat who liked to swim — but it’s really about Morris learning that he lived a celebrated life, despite not ever finding a partner. What he found was equally important, in that he was fully aware of his passions and how to pursue and celebrate them.

“He collected the stories of this place,” we’re told in an opening placard, and as Morris witnesses how the world is moving on without him, we see the importance of history and how the museum work of Morris allows the world to better evolve.

In one sense, “Necrobarista” is the most accessible of the games mentioned here, in part because it’s available for Apple’s mobile subscription service Apple Arcade, but the sci-fi anime story and the way it remixes the idea of an interactive novel might require getting used to. Still, the concept of “Necrobarista” (PC, iOS) — we have 24 hours in a bar/coffee shop after we die before we move to the next plane — continues to haunt me, particularly in how it views time. The recently dead gamble with time, hoping to get a few more hours to stay among the mortals, which in turn makes time a currency.

Time becomes currency in the haunting “Necrobarista.”

(Route 59 Games)

We meet a recently deceased dude who’s desperate for more hours. “I don’t think anyone here properly understands what it’s like to see your last sunrise ever,” he pleads. With the world feeling on hold for so many of us, I’ve let the concept of time weigh on me. Until this pandemic ends — in who knows how many months or, worse, years — I’ve lost time to see the world. And I’ve lost time to find a partner. Or so I think. These false thoughts can be paralyzing and lead, as they have for me, to emotional spiraling. It’s these type of worries that led to the corrupt world of “Necrobarista.”

The concept of time is present in all these games, and in “What Comes After” lessons are delivered by a flower, plucked early in life to be used as a decoration in a floral arrangement that was presumably given on Valentine’s Day. The plant scolds Vivi — oh, the subway train that connects this world to the afterlife has a forest on it — and she promises not to kill plants in the name of accessories or gifts to a lover if she opts to continue living. The plant says she’s missing the point; flowers exist to be beautiful.

“How do you expect to find love if you can’t even wait for a flower to fully bloom?” says the sad little sprout, frustrated with the impatience of humans and our tendency to try to will time to our needs.

I took a bunch of screenshots of this corny scene because it made me smile. I like to think there’s a post-pandemic future where we all blossom again. But the time it takes to get there is only lost if we don’t discover how to embrace the growth along the way.