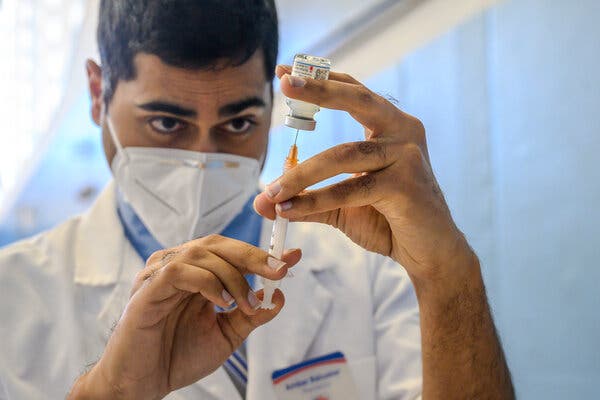

The suspension of the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine by most governments across Europe has further set back an already fraught inoculation campaign rolling out on the continent and threatened to rattle the vaccination effort in dozens of other countries around the world.

No country in the European Union is on pace to reach the goal of vaccinating 70 percent of its population by September, even as hundreds of millions of people across the continent are still constrained by some of the most severe coronavirus restrictions in the world. Millions more are facing the prospect of rules being tightened further to combat a third wave of the coronavirus.

So far, the vaccine efforts have been marked by political infighting, mixed messaging to the public, a shortage of supply and a lack of solidarity. And with many of the national vaccination strategies heavily reliant on the vaccine made by AstraZeneca, the decision to suspend its use while the bloc’s regulatory body looks into concerns about its safety — though that regulator has continued to describe it as safe and effective — will slow things down even more.

Spain joined France, Italy, Germany and other in halting the use of the vaccine over concerns about the possibility of rare side effects including blood clots and abnormal bleeding. The hesitancy of European governments may also undermine public confidence in the vaccine, which could have implications far beyond Europe.

The World Health Organization was quick to react to moves by European governments, hoping to prevent a broader panic. It said on Monday that there was no evidence to suggest its use was unsafe.

Millions of people in dozens of countries have received the AstraZeneca Covid vaccine with few reports of ill effects, and its prior testing in tens of thousands of people found it to be safe. All the governments in Europe that suspended its use said they were acting simply out of an abundance of caution while the bloc’s regulatory body reviewed the data. It is expected to hold an emergency session on Thursday but its guidance, as of Tuesday morning, remained that the vaccine was both safe and effective.

The AstraZeneca vaccine, developed in partnership with Oxford University, was designed to be the workhorse of the global vaccination effort — with some two billion doses ordered for use in more than 70 countries this year.

It is being sold using a nonprofit model and is far cheaper than other vaccines. It can be stored more easily and has already started to be shipped to low and middle income countries that signed onto the global vaccine sharing program known as Covax.

While some countries have suspended the use of AstraZeneca’s coronavirus vaccine over safety concerns, Thailand on Tuesday kicked off a program for its distribution nationwide, with Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha receiving the first shot.

Thailand is one of several countries, including Australia and India, that are continuing to use the AstraZeneca vaccine as experts investigate reports of fatal brain hemorrhages and blood clots among a handful of people who received it. Millions of people around the world have been inoculated with the AstraZeneca vaccine, and scientists say there is no evidence that it causes blood clots, which can occur for any number of reasons.

More than a dozen countries, mostly in Europe, have paused AstraZeneca vaccinations in the last few days, raising fears that vaccinations will be disrupted at a critical time. In Asia, Indonesia also said on Monday that it would not start distributing the AstraZeneca vaccine until it could determine that it was safe.

The AstraZeneca vaccine, which has been authorized in more than 70 countries, is seen as key to fighting the virus in the developing world because it is cheaper and easier to store than other vaccines.

Thailand on Friday became the first country outside Europe to delay use of the AstraZeneca vaccine, which Mr. Prayuth had been scheduled to receive that day. By Monday, however, officials said they had received information from the World Health Organization and the European Medicines Agency confirming that the vaccine was not connected to the occurrence of blood clots and was safe to use.

In an event on Tuesday that was broadcast online, Mr. Prayuth, 66, selected a vial from a box of AstraZeneca vaccines, inspected the label and received his shot as officials around him applauded.

“I feel good,” he said moments later. “This will build confidence for the general public in the government vaccination program.”

AstraZeneca is one of two vaccines authorized for use in Thailand, with the Thai company Siam Bioscience expected to produce 61 million doses by the end of the year.

Other countries agree that there is insufficient evidence to justify suspension. In a statement on Tuesday, the Australian medicines regulator said it had not received any reports of blood clots among people who had received the AstraZeneca vaccine. Greg Hunt, the health minister, also said the government supported continued use of the shot.

“There have been views expressed — we disagree with them clearly, absolutely, unequivocally,” he said in Parliament.

AstraZeneca is central to Australia’s vaccination drive, with most of the 53.8 million doses the government has secured being manufactured domestically.

Officials in India, where the AstraZeneca vaccine is manufactured locally and known as Covishield, have said there is no immediate concern. They are reviewing data on adverse effects for the AstraZeneca vaccine and for the other shot being used, a domestic vaccine called Covaxin.

The drug company Moderna has begun a study that will test its Covid vaccine in children under 12, including babies as young as six months, the company said on Tuesday.

The study is expected to enroll 6,750 healthy children in the United States and Canada.

“There’s a huge demand to find out about vaccinating kids and what it does,” said Dr. David Wohl, the medical director of the vaccine clinic at the University of North Carolina, who is not involved the study.

In a separate study, Moderna is testing its vaccine in 3,000 children ages 12 to 17.

Many parents want protection for their children, and vaccinating children should help to produce the herd immunity considered crucial to stopping the pandemic. The American Academy of Pediatrics has called for expansion of vaccine trials to include children.

Each child in Moderna’s study will receive two shots, 28 days apart. The study will have two parts. In the first, children aged 2 years to less than 12 may receive two doses of 50 or 100 micrograms each. Those under 2 years may receive two shots of 25, 50 or 100 micrograms.

In each group, the first children inoculated will receive the lowest doses and will be monitored for reactions before later participants are given higher doses.

Then, researchers will perform an interim analysis to determine which dose is safest and most effective for each age group.

Children in part two of the study will receive the doses selected by the analysis — or placebo shots consisting of salt water.

The children will be followed for a year, to look for side effects and measure antibody levels that will help researchers determine whether the vaccine is effective. The antibody levels will be the main indicator, but the researchers will also look for coronavirus infections, with or without symptoms.

Dr. Wohl said the study appeared well designed and likely to be efficient, but he questioned why the children were to be followed for only one year, when adults in Moderna’s study are followed for two years. He also said he was somewhat surprised to see the vaccine being tested in children so young this soon.

“Should we learn first what happens in the older kids before we go to the really young kids?” Dr. Wohl asked. Most young children do not become very ill from Covid, he said, though some develop a severe inflammatory syndrome that can be life threatening.

Johnson & Johnson has also said it would test its coronavirus vaccine in babies and young children after testing it first in older children.

Pfizer-BioNTech is testing its vaccine in children ages 12 to 15, and has said it plans to move to younger groups; the product is already authorized for use in those 16 and up in the United States.

Last month, AstraZeneca began testing its vaccine in Britain in children 6 years and older.

In a city scrambling to vaccinate people against Covid-19, Ambar Keluskar faced a problem that seemed to defy logic: The pharmacist, based in Brooklyn, struggled to find people to take the 200 doses he had on hand this month.

State rules restricted who could get shots at independent pharmacies like his to certain older residents, and fewer and fewer people seemed to be scheduling appointments. The problem was even more vexing because his pharmacy, Rossi Pharmacy, draws many customers from East New York — a community that has been hit hard by the pandemic, and whose vaccination rate lags behind other parts of New York City.

Mr. Keluskar’s pharmacy spent hundreds of dollars on Facebook advertisements to let people know that he had available doses. He asked community leaders to spread the word. Then he decided to try a different approach: Instead of waiting for people to come to the pharmacy, he would take his doses to them.

Vaccine providers and would-be recipients alike have been confronted by bureaucratic eligibility rules, a shifting understanding of the virus and a sign-up system that can be prohibitively complex. Vaccinations have been slower to reach many communities where the virus has inflicted the highest toll, and where people may not have the time or resources to easily sign up for appointments.

In response to these problems, volunteers and community groups have built appointment websites, hosted pop-up clinics at churches and helped eligible neighbors navigate the process.

Among those seeking to fill that void was Mr. Keluskar, who this month vaccinated almost 50 people at a senior affordable housing complex near downtown Brooklyn who were homebound or struggling to find appointments.

“The patients loved it,” he said. “They got to get vaccinated somewhere local.”

GLOBAL ROUNDUP

Papua New Guinea, which had largely avoided the coronavirus, is now sounding the alarm over an outbreak that its prime minister said could infect up to a third of the country’s population.

The small island nation has recorded 2,269 coronavirus cases and 26 deaths since the beginning of the pandemic, according to the country’s health department. Nearly half of the infections were recorded in the last two weeks, and 97 cases were reported on Sunday.

On Monday, Prime Minister James Marape called the situation “critical” and said that restrictions on movement would be brought in. The nation’s business will be allowed to remain open, but residents will not be allowed to leave their provinces or villages.

Only about 55,000 of the nation’s nine million people have been tested for the coronavirus, a low rate that signals the actual number of infections may be much higher than reported.

There are also concerns that the country’s fragile health system will buckle under the strain, and that recently held gatherings to commemorate former Prime Minister Michael Somare, who died last month, would become super-spreader events.

The spike in cases has prompted concerns in neighboring Australia that the outbreak could spread to its shores. The Torres Strait Islands, an autonomously administered group of islands, are just two and a half miles from Papua New Guinea at the nearest point.

Aid groups and Australia’s opposition party have urged the government to provide emergency vaccine doses to Papua New Guinea. The smaller nation has sourced 200,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine from Australia and 70,000 from India, but is not expected to get its first vaccine doses until at least next month.

In other developments across the world:

-

Prime Minister Boris Johnson of Britain on Tuesday defended the safety and efficacy of the AstraZeneca vaccine, which was produced with the University of Oxford. “That vaccine is safe and works extremely well,” he said in The Times of London, arguing that the nation’s inoculation campaign would bear fruits only if other countries had successful vaccine rollouts. “Successful as the U.K. vaccination program may be, there is little point in achieving some isolated national immunity.”

-

In France, the authorities identified a new variant of the coronavirus that does not appear to be deadlier or more contagious than other variants but that could be harder to detect with traditional testing. Eight cases of the variant were identified in a cluster of infections at a hospital in the western region of Brittany. Local health authorities said the variant was not “worrying” but would be closely monitored. Some of the people infected with the new variant cases had tested negative with a PCR nose swab, even though they had symptoms and more thorough testing showed that they had Covid-19.

-

Officials in France acknowledged that temporarily suspending use of the AstraZeneca vaccine would slow down the country’s vaccination campaign, but said that caution was necessary. Alain Fischer, an immunologist who heads the government’s vaccination advisory council, told France Inter radio on Tuesday that the suspension was a “hard blow” but that it was “reasonable to be cautious.”

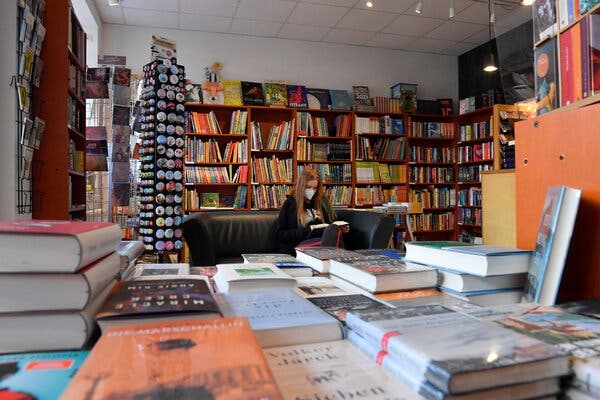

A German children’s book on the coronavirus was removed from bookstore shelves after Chinese diplomats complained to the publisher about a passage on the virus’s origins.

In the book — which was written to explain the pandemic, lockdown measures and hygiene rules to children — Moritz, an elementary-school boy says, “The virus comes from China and has spread from there around the world.”

The Chinese Consul General of Hamburg made a complaint about the book to the district attorney’s office, according to a semiofficial Chinese news blog, German-China.

“With the malicious claim that the coronavirus originated in China, a German children’s book has caused outrage in the Chinese community in Germany,” the blog’s authors wrote.

In the past year, the Chinese state has tried to gloss over the provenance of the virus in favor of how well China has dealt with its outbreaks. Early in the pandemic, a title page in the newsmagazine Der Spiegel with the phrase “Coronavirus Made in China” caused outrage among Chinese diplomats.

Although research made public late last year indicated that the virus may have infected people in the United States and elsewhere earlier than previously thought, researchers still believe that it probably first began circulating in China.

Carlsen, the Hamburg-based publisher of the children’s book, said that the book had been written last spring, and that if writing it today, they wouldn’t have phrased the information quite the same way.

“Today we would not use this formulation, which has proved to have a far more ambiguous meaning than we intended,” Katrin Hogrebe, a spokeswoman for the publisher, said in a statement.

The sentence in question does not appear in a new edition of the book.

With Covid-19 deaths rising to their highest levels yet and a dangerous new virus variant stalking Brazil, the nation’s communications minister went to Beijing, where he met with Huawei executives and made an unusual request.

“I took advantage of the trip to ask for vaccines,” said the minister, Fábio Faria, recounting his meeting with Huawei, the telecommunications giant, last month.

Two weeks later, the Brazilian government announced the rules for its 5G wireless network auction, one of the biggest in the world. Huawei, which the government appeared to have barred just months before, would be allowed to participate.

The about-face is a sign of how politics in the region have been scrambled by the pandemic and President Donald Trump’s departure from the White House — and how China has begun to turn the tide.

China spent months batting away resentment and distrust as the place where the pandemic began, but in recent weeks its diplomats, pharmaceutical executives and other power brokers have been fielding scores of requests for vaccines from officials in Latin America.

Beijing’s ability to mass-produce vaccines and ship them to countries in the developing world — while rich countries like the United States are holding many millions of doses for themselves — has offered a diplomatic and public relations opening that China has seized.

Suddenly, Beijing finds itself with enormous leverage in Latin America, a region where it has a vast web of investments and ambitions to expand trade, military partnerships and cultural ties.

The precise connection between the vaccine request and Huawei’s inclusion in the 5G auction is unclear, but the timing is striking, and it is part of a stark change in Brazil’s stance toward China. The president, his son and the foreign minister stopped criticizing China, while cabinet officials with inroads to the Chinese, like Mr. Faria, worked furiously to get new vaccine shipments approved. Millions of doses have arrived in recent weeks.

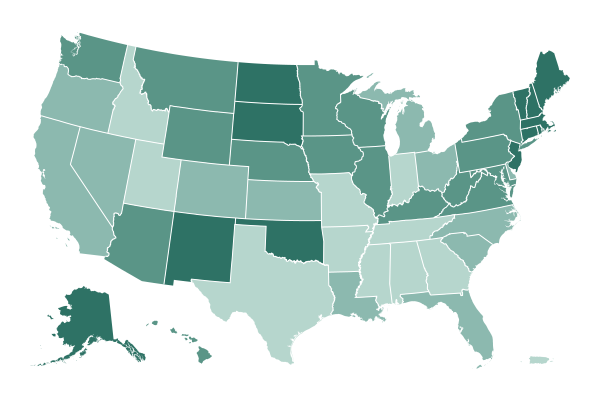

As people across the United States jockey and wait to get vaccinated, a different problem is unfolding in the Cherokee Nation: plenty of shots, but not enough arms.

It is a side effect of early success, tribal health officials said. With many enthusiastic patients inoculated and new coronavirus infections at an ebb, the urgency for vaccines has gone quiet.

Now, the tribe is confronting what looms as a hurdle for the whole country as vaccine supplies swell to meet demand: how to vaccinate people who are not eagerly lined up for a shot.

That public health challenge encompasses persuading skeptics, calling people who don’t realize they are eligible, and making vaccines accessible for homebound patients, overstretched working families and people in rural areas and minority communities.

The Cherokee Nation has administered more than 33,000 doses at nine vaccination sites across its reservation, which spreads from cities through rural woodlands, cattle pastures and poultry farms in northeastern Oklahoma. After vaccinating health care workers, Cherokee-speaking elders and essential workers, the tribe opened appointments to anyone who qualifies, tribal member or not, living in its borders.

Still, hundreds of slots have gone unfilled, health officials said. Cherokee-speaking vaccine schedulers hired to set up appointments are waiting for their phones to ring.

The Osage Nation, in northeastern Oklahoma, is vaccinating about 200 people a day at a clinic that has the capacity to give 500 shots. It tried two mass vaccination events at its casinos, but the results were disappointing.

So the tribe bought two 30-foot “medical RVs” that will roll into smaller towns like Hominy and Fairfax to reach the 30 to 40 percent of tribal elders and essential workers who did not volunteer to get vaccinated. It is a house-by-house campaign against misinformation and wariness, waged with long conversations and patience.

“We tried to remove every obstacle to people who were sitting on the fence,” said Dr. Ronald Shaw, the medical director of the Osage Nation.

Chinese embassies in a rapidly growing number of countries, including the United States, have begun requiring that foreigners entering China must first be fully inoculated with a Chinese-made coronavirus vaccine if they want to avoid extensive paperwork requirements.

Complying with the rule will be difficult for people applying for Chinese visas in places that are not offering vaccines produced in China. No Chinese-made vaccine has been approved in the United States or most of Europe.

Many regulators outside China have been wary of vaccines made by companies in China, notably Sinovac and Sinopharm. The companies have released relatively little data from Phase 3 trials to allow independent assessments of the vaccines’ efficacy and safety.

The Chinese Foreign Ministry announced similar rules for foreigners wanting to enter the Chinese mainland from Hong Kong. It said on Saturday that if they received a Chinese-made vaccine they would not need to meet other requirements, including a negative nucleic acid test, detailed health and travel records, and a personal invitation from a Chinese provincial government agency.

Some foreigners who live and work in the Chinese mainland but left early in the pandemic have been living in limbo for a year or more in Hong Kong, which has authorized the Sinovac and BioNTech vaccines, and elsewhere.

By Tuesday morning, Chinese embassies had issued identical rules in Britain, Japan, Norway, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand, the United States, Vietnam and at least a dozen other countries.

The Chinese stance puts pressure on other countries to give regulatory approval to China’s vaccines. Beijing has not allowed vaccines developed in other countries to be produced or administered in China.

Thousands of businesspeople and students have been seeking visas to resume their work or studies in China. The country’s borders have been among the most tightly closed in the world to prevent the coronavirus from re-entering the country after being largely stamped out. Business leaders say the new vaccine recommendation adds to the hurdles.