In Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, the protagonist Saleem Sinai returns to the city of his birth – then called Bombay, officially renamed Mumbai in 1995 – in a third-class train carriage, lulled by the familiar chant: “abracadabra abracadabra abracadabra sang the wheels as they bore us back-to-Bom”. He finds it changed, its shoreline reclaimed from the sea, the skyline transformed with new billboards. “Yes, it was my Bombay, but also not-mine.”

I fell in love with Mumbai nearly 15 years ago while riding its local trains. On these packed carriages hurtling through the length of the city, I found a sense of unfettered mobility and unfolding possibilities that felt new and entirely thrilling. By the wide entrance doors of the ladies’ compartment, I saw women chopping vegetables in preparation for their evening meals. Behind the chaos, I found rules: I was expected to know when to start queuing to disembark (at least two stops before my station), and to vacate my seat halfway through my journey to allow a fellow passenger to sit.

As a young, working woman recently arrived from northern India, savouring my new job and newfound independence, all this seemed beguilingly, irresistibly modern. Which was probably part of the idea behind the railway itself. Even today, millions of commuters and migrants spill into the city through the magnificent portals of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, formerly the Victoria Terminus, under a domed ceiling topped by a statue of Progress.

In the mythology of metropoles around the world, Mumbai occupies a space all of its own. A sprawling, glittering muse, it has inspired countless tellings and retellings in India and abroad. Rudyard Kipling, born here, called it his “Mother of Cities”. Crime writer HRF Keating located The Perfect Murder here without ever setting foot in the city. Poet Allen Ginsberg saw it first in a dream, sailing into its glittering harbour at night. On his actual arrival three months later, he found it to be “like a shabby, Victorian-era London with some art deco edges”, writes Deborah Baker in A Blue Hand: The Beats in India. In a letter to a friend who had described the city in unflattering terms, Ginsberg grumbled: “I must say, you made it sound as if a westerner would die of rat poison if he stayed anywhere but Taj Mahal Hotel.”

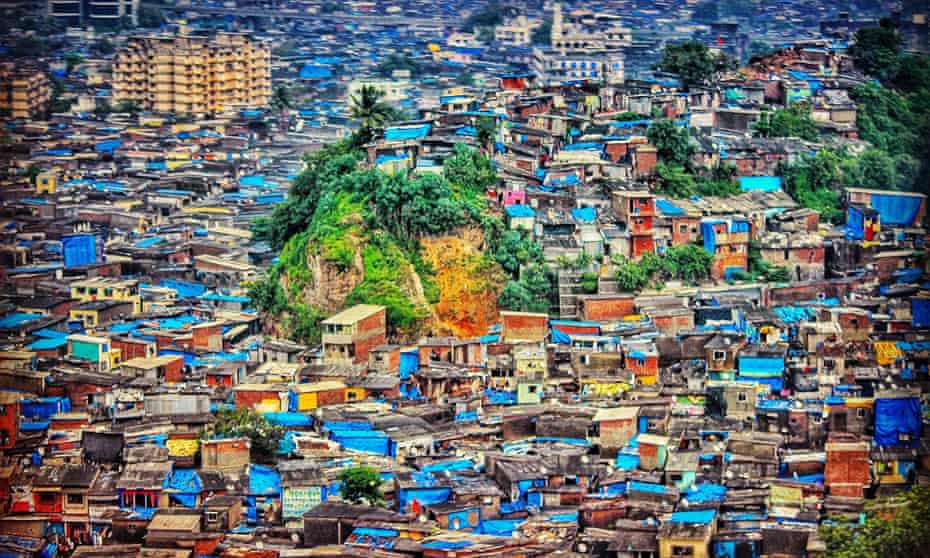

Hundreds of popular films are produced here each year – a legacy, perhaps, of the first screening by the Lumière brothers at the now-dilapidated Watson’s Hotel. For a generation of cinema buffs, Mumbai is familiar as the setting of Slumdog Millionaire. But for the more curious traveller, it is both greater than the sum of its parts, and smaller – visible in the details.

No single tour can capture this densely folded multitude, or even the many languages it speaks. But one way of delving into this city of 12 million souls is through the rhythms of its everyday life, in all their rich textures and detailsTo move like a clickety-clack pulse, traversing its changing terrain.

Read

Swing through Mumbai’s mostly forgotten jazz age in Naresh Fernandes’s Taj Mahal Foxtrot. From visiting American bands to Indian performers, the book zips across dancefloors and lit-up ballrooms, mapping a city of diversity and easy cosmopolitanism. The south Mumbai locality of Byculla, close to the dockyards of Mazagaon on the eastern waterfront, provides the setting for many of the stories in Altaf Tyrewala’s No God in Sight – a landscape inflected by the communal violence that tore the city asunder in the early 1990s.

Follow the flaneur figure of Saadat Hasan Manto around the working-class localities of Madanpura and Nagpada. The controversial author was part of a group of Urdu writers who flocked to the city in the 1940s, many of whom also wrote for the movies. The English translation of his profiles of film personalities of the era, Stars from Another Sky, has been described as “a Midaq Alley of Bollywood” by Mumbai-based author Jerry Pinto.

Journalist Kalpana Sharma’s Rediscovering Dharavi: Stories from Asia’s Largest Slum mapped the complicated interplay of industry and poverty in this sprawling settlement long before Dharavi became a global buzzword. Sonia Faleiro’s work of nonfiction, Beautiful Thing, is a moving investigation into the lives of Mumbai’s bar dancers, told through her protagonist Leela, who navigates hypocrisy and exploitation while cherishing her own hard-won financial freedom. And Meenal Baghel’s Death in Mumbai delves into the sensational murder of a young television executive in 2008 to create a portrait of an increasingly breathless news media, and the reshaping of India’s popular culture by production houses in the booming suburb of Oshiwara.

Watch

In the wealth of documentaries about Mumbai, the work of Anand Patwardhan turns a consistent gaze on the city. For more than three decades, from the displacement of slum dwellers in Bombay Our City (1984) to the thrust of Dalit politics and poetry in Jai Bhim Comrade (2011), Patwardhan has captured the complicated coexistence of ugliness, violence and hope on its streets.

Ask the Sexpert by Vaishali Sinha takes a hilarious, moving journey into the city’s mind and libido, via 93-year-old sexologist Dr Mahinder Watsa, who wrote a popular and long-running advice column in a local newspaper.

The era of clashes between Mumbai’s cops and underworld dons is preserved in popular films preoccupied with the city’s fabled underbelly. These range from 1990s cult favourite Satya, about a migrant sucked into a life of crime, to the more recent Sacred Games, lavishly produced by Netflix, based on the novel of the same name by Vikram Chandra.

To explore the relationship between the city and its large film industry, plunge into Miss Lovely, set in the world of 1980s C-grade movies – sleazy sex/horror productions – moving through small studios, hotels, and gangland money. As an antidote to all that reality, try the period charm of the 1970s romcom Chhoti Si Baat, about a shy young man’s attempts at romance on the office commute. Its delightful song routines include glimpses of Mumbai’s iconic red buses, cafes and cinemas.

The clash between modernity and tradition inside the baugs, or housing colonies, of Mumbai’s Parsi community plays out in Little Zizou, the charming story of a motherless boy who dreams of meeting his hero, the footballer Zinedine Zidane. The medley of languages in the dialogue – English, Hindi, Gujarati – is one way of gauging Mumbai’s diverse linguistic terrain.

Listen

Rain lashing Mumbai during its dramatic monsoons is immortalised in dozens of film songs, often shot on one of the promenades. Here’s a personal favourite: Rim Jhim Gire Saawan, from the 1979 film Manzil, featuring a romantic walk along the sweep of Marine Drive, the art deco-studded seafront built on land reclaimed in the 1920s. Also catch glimpses of the Oval Maidan, a rare open space in a densely populated city.

The soundtrack of the recent Gully Boy draws from the work of Mumbai’s real-life rap and hip-hop performers. Its hit track Mere Gully Mein (“On my street”) is a catchy, powerful evocation of the singer’s bustling neighbourhood. Equally addictive is the 1960s bilingual Indi-pop tune Bombay Meri Hai (“Bombay is mine”), declaring: “Our ladies are nice, gents are full of spice/ Bom Bom Bom Bom Bom Bom Bombay hurray!”

On most days, Mumbai’s streets hum with a soundtrack of traffic noise and film songs, religious compositions and regional hits. Before the pandemic, most weddings and festive processions passing outside my window were accompanied by the beats of the wildly popular Marathi song Zingaat (from the film Sairat), as well as Sia’s Cheap Thrills.

But through passing decades and shifting tastes, the unofficial anthem of the megacity remains this evergreen song from the 1956 crime thriller CID:

“Zara hat ke, zara bach ke, yeh hai Bombay meri jaan.” (“Watch your step, mind yourself, this is Bombay my love.”)

Taste

In 1972, prominent Mumbai poet Nissim Ezekiel was inspired to write his poem Irani Restaurant Instructions by a list of rules displayed at Bastani, an Irani cafe in the south Mumbai locality of Marine Lines.

“Please

Do not spit

Do not sit more

Pay promptly, time is invaluable”

These atmospheric eateries, with their characteristic high ceilings and bentwood chairs arranged around glass-topped tables, are fast vanishing from the streets of Mumbai. The popular UK restaurant Dishoom paid affectionate homage to these spaces in Dishoom: From Bombay with Love, a cookbook that mixes memories and anecdotes with recipes.

Mumbai’s diversity is reflected in its food map: it’s possible to sample expensive eateries and street food on the same stretch of road; to move from south Indian food in the suburb of Matunga to Bohri dishes in south Mumbai’s Bhendi Bazaar. This variety is one reason why Mumbai has drawn a large number of chefs to its streets, from Anthony Bourdain to Gordon Ramsay.

Indian food writer Vikram Doctor casts a wide net for his subjects, but often turns his gaze to Mumbai, combining history and current affairs to create unlikely connections to our plates – in this column about Mumbai’s favourite mango, the alphonso, or this podcast episode on bombay duck, the aromatic dried fish.

The range of flavours in Maharashtrian food is at the heart of Saee Koranne-Khandekar’s cookbook Pangat, a Feast: Food and Lore from Marathi Kitchens. Parsi food, and food stories from the community, are the stars of the podcast Not Just Dhansak, hosted by Perzen Patel.

See

In pre-pandemic Mumbai, you could strike a pose with the Gateway of India for one of the photographers strolling around the harbour and walk away with a keepsake picture chugged out on a portable printer within minutes. Until a return to this buzzing waterfront is possible, take in the view with the virtual tour here.

The city museum, or Dr Bhau Daji Lad Museum, and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya also have tours and online exhibitions, as does the National Gallery of Modern Art. The Royal Opera House, a splendid baroque structure that reopened in 2016 after a renovation, has been hosting online concerts and events, as well as a virtual tour that is dazzling even on your screen.

Several Instagram accounts follow a trail of beauty around the city, from its art deco balconies and ornate elevator grilles, to its Bollywood-hued wall art; from marine life and avian visitors to the trippy ceilings of its taxis. Advertising professional and photographer Gopal MS posts vignettes and stories from the streets on the popular Mumbai Paused. Or explore the lives of the Koli community with Ganesh Nakhawa’s handle The Last Fisherman of Bombay, a reminder of the complicated, perennial embrace between the city and the sea.

Taran N Khan is a journalist and writer based in Mumbai. She is the author of Shadow City, A Woman Walks Kabul, published by Penguin at £9.99