William Crossing wrote more than 15 books about Dartmoor, with titles including Amid Devonia’s Alps, The Land of Stream and Tor, and Tales of the Dartmoor Pixies. Needless to say, he adored the place. Born in Plymouth in 1847, Crossing lived in the villages of South Brent, Brentor and Mary Tavy, and over five decades got to know Dartmoor’s people, traditions, history and prehistory better than anyone. Though the leading chronicler of his time, he is nowhere near as famous today as Alfred Wainwright – just as Dartmoor isn’t as eulogised, romanticised or popular as the Lake District.

When people want to celebrate Dartmoor, they’ll talk about it being “the highest point in England south of the Pennines”. But this is missing the point. For all that the tors are quite lofty, very photogenic and lovely at dusk and dawn, they are hardly soaring summits. Dartmoor’s mires are energy-sapping. Its forests are small, the native oaks stunted, the conifer plantations lifeless.

Sometimes, on days of cold mizzle and eventless grey, Dartmoor can be hard to love. Its essentially gloomy, weatherbeaten character comes to the fore, sucking your shoes into the mud, slapping you on the cheeks and wrapping the sun behind murky clouds so that you wonder what time of day it is. Hikers more used to the Yorkshire Dales or Snowdonia complain that the landscape is featureless and navigation confusing.

When I first walked the moor, after relocating to Totnes in 2014, I found it hard even to see it – in the senses of observe, make sense of and appreciate. I had acknowledged it as a brooding presence on drive-bys along the A38, but found that the closer you get the less you behold. The lanes that crawl up its sides are more often than not buried inside deep hedgerows. Every corner is blind and dangerous; every vista glimpsed is quickly cut off by another wall of greenery.

But, slowly, I got to know and value the subtleties of this unusual landscape – essentially a mountain smoothed and polished till it became something like the ghost, or memory, of one. My favourite line in the King James Bible is the one in Genesis about the world before the Creation being “without form, and void”. Dartmoor is pretty formless and empty, and that’s what makes it remarkable. It reminds me a little of the Russian steppes, and of Patagonia – vastnesses where you don’t see anything you could really call a contour for mile upon mile. But you can feel absolutely free in such open spaces, and you can walk for miles without obstacles or distractions. You can see all the changes of the seasons on such an empty canvas, the colour switching from green to brown to gold. Clouds flit over the tops, adding variations on the same palettes.

Over seven years, I found many things to appreciate about “the moor”, as it’s known by all who live around its edges: the lines and circles of ancient stones, the ruined settlements, the rail tracks and quarries, the rabbit holes and crumbled walls, and all that remains of the work and lives of the miners, warreners, drystone wall builders and peat cutters who were still a presence in Crossing’s day. The sheep, cattle and ponies continue to make work for a few score Dartmoor folk.

Cuckoos, skylarks, meadow pipits, buzzards, the occasional raven, and ever-homeless herring gulls cast their more or less musical efforts on to the upland breezes. Sleeping out on the moor for a night – which I’d recommend to all – you have the company of owls and the night neighs of the ponies. There is not nature in great abundance, unless you’re a lover of mosses, lichens and ferns. But it’s arguable you see more of something when there is less choice, fewer things vying for your attention.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the creation of Dartmoor national park. A new train service (see below) and the likelihood of UK-only holidays for most will mean more people than ever come to explore it this summer than ever before. Perhaps climbers – or walkers, anyway – can start to baptise the high places, with or without tors, as “Crossings”, just as Scotland has its Munros.

I, however, am leaving the area. During the pandemic, Dartmoor was my happiest socially distanced place, but I feel I’ve walked some paths so often they have sunk a few inches. I could climb, circle or point to Ugborough Beacon blindfolded. I’ve explored north, south, west and east, driven, walked and cycled every corner, slept at selected spots when the law allowed. I’ve lost a welly in a mire, wandered a little too close to red flags on war games days and, for one hardcore birthday treat, hired a pushbike without checking beforehand which arduous ascents and sharp descents to avoid.

We need a break, the Moor and I. I shall come back one day to be surprised by Dartmoor, first when it rears up at the end of the M5, then again and again as it reveals its quiet, gloomy but entrancing spirit.

Explore the northern moor

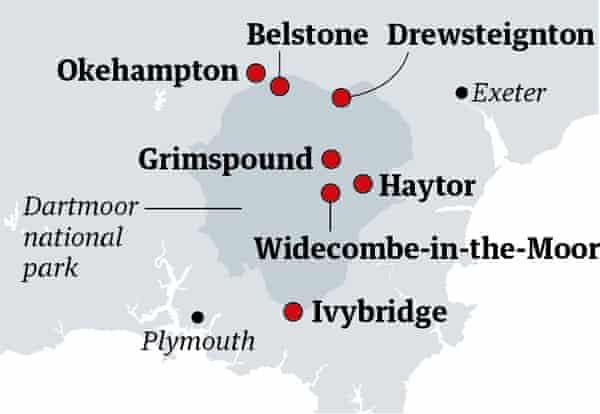

A new, daily train service on the 14-mile Exeter-Okehampton Dartmoor Line restarts this year after a 50-year absence. It will run every two hours (hourly from 2022), and brings paths north of Okehampton within easy reach, as well as a large swath of the north-western moor controlled by the MoD. From Okehampton, it’s easy to do a circular walk around West Mill Tor, Rowtor and Scarey Tor, returning via the lovely Tors Inn at Belstone. The nine-mile climb from Meldon Dam car park up to the two highest points on Dartmoor – High Willhays and Yes Tor – is easy enough so long as it’s not lashing down. Check firing times on the MoD range here.

Over the hump of Hameldown

This long ridge is more fun to walk than to look at. Easily accessed from its southern tip near Widecombe-in-the-Moor (which has two fine pubs, the Old Inn and the Rugglestone Inn), it’s a gentle climb to a series of high points – including Hameldown Beacon at 517 metres and Hameldown Tor at 530 metres – and the English Heritage bronze age hut circles at Grimspound. Its spine offers sweeping views around all four points of the compass – to Torbay, the TV and radio mast at North Hessary Tor near Princetown, and the south Devon coast.

Find the hidden tors

At weekends and in summer, locals and tourists alike congregate at the granite Haytor. It’s a looker, with plenty of walls and crevices for climbers and older kids, and is close to the B3387 and car parks. It is, along with near neighbours Greator Rocks and Hound Tor, one of Dartmoor’s most popular spots. But the moor has at least 160 tors – Crossing said no one could ever calculate the true number as there’s no real definition of a tor, other than a rocky outcrop prominent enough to be considered a landmark.

Striking tors that are off the radar include Lower White Tor, Higher White Tor, Rough Tor and the remote Fur Tor. And scattered all over are smaller piles of scree and clitter that don’t draw the crowds, as well as little craters and barrows where you can hunker down with a flask. Look out for letterboxes at the bigger tors: while Crossing did not invent “letterboxing” (a combination of hiking, orienteering and treasure hunting), it was he who made the hobby well known around Dartmoor.

Wild camping

Dartmoor is the only English national park where wild camping is allowed. A few rules need to be observed to keep this “no impact”, as the park authorities say: camp well away from roads and settlements; stay one or two nights only; check the map at dartmoor.gov.uk and camp only in purple zones; use small tents and don’t light fires or barbecues. I’d strongly recommend eastern slopes – out of the prevailing wind. The best sites are usually among hawthorn, gorse and other scrubby trees. Wild camping was banned in lockdown, but may be allowed from 12 April.

Massif multi-day walks

Because Dartmoor doesn’t have peaks to conquer, those walkers who seek the satisfaction of achieving a goal should do a two-, three- or five-day walk. Going slowly over a few days, you begin to really see that the apparently formless lump is in fact a gently undulating massif, crossed by rivers and streams, with surprising copses buried away inside deep fissures. The Two Moors Way, running south to north, links Ivybridge with Drewsteignton – a distance of around 37.5 miles – and then continues to Exmoor (a total of 102 miles).

The Dartmoor Way is a 108-mile circular route around the moor. Both of these routes lend themselves to long walks, with camping either wild or at official sites. It’s also fun to head for one of the moorland villages and pick a destination at random. I walked from Holne to Chagford one weekend and was impressed by the mix of ancient sites, woodlands, charming hamlets and wilder empty spaces I came upon. I met no more than a dozen people over 15 hours of walking.

The 37-mile West Devon Way between Okehampton and Plymouth is a good option for those who come by bus or train: each of the eight stages starts and stops at a bus stop. Then there is the 95-mile Dartmoor Cycle Way, which loops round the park on lanes and minor roads. Good maps are essential, even on well-marked trails; get the OS to print you a bespoke 1:25,000 Explorer(s) for your route (with digital download) or use BMC XT40, a single 1:40,000 scale map showing the whole of Dartmoor.