It’s a household divided.

One morning in February, 15-year-old Lewis Polansky and his 13-year-old sister Elsa reported to Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine trial site in Banning, Calif., for their experimental shots.

Back home in South Pasadena by midafternoon, Lewis rubbed his sore arm, complained of fatigue and fell asleep. Elsa, who felt nothing, was jealous.

“I probably got the placebo,” she said with a groan.

Elsa had joined the trial in hopes of being among the first children to be vaccinated — and feeling safe enough to visit Disneyland when it reopens.

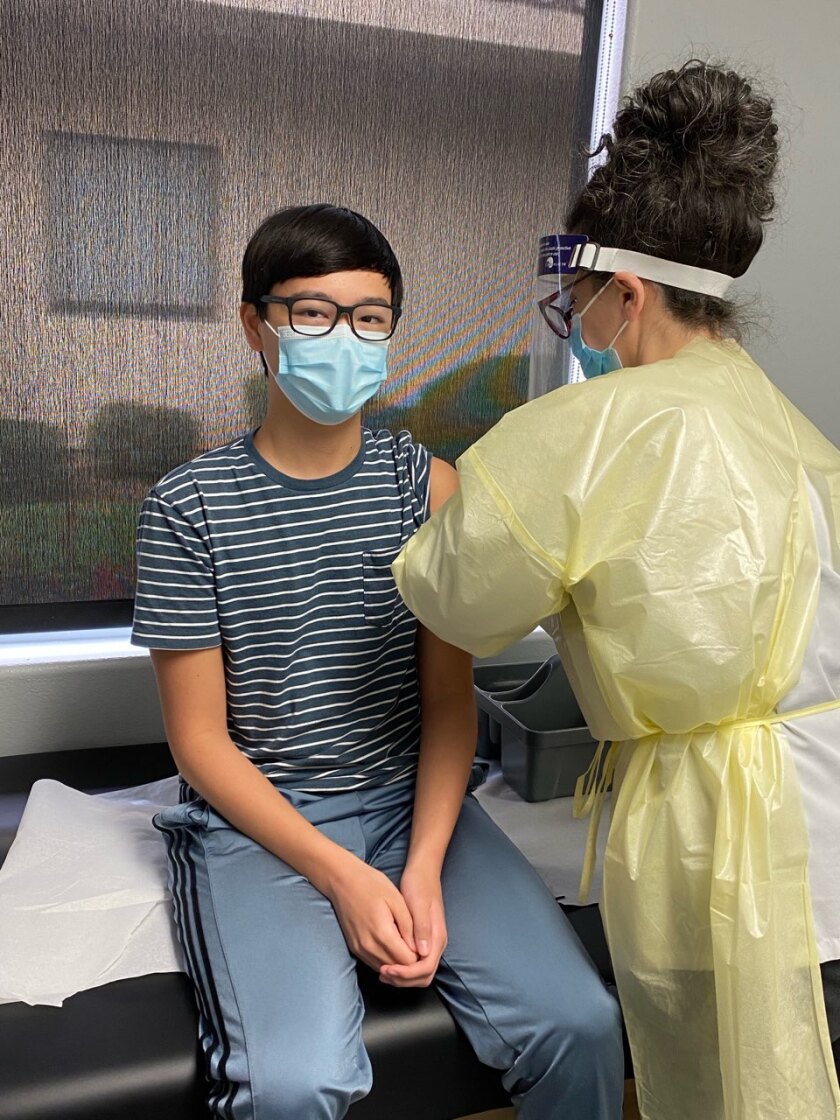

Elsa Polansky, 13, receives an injection as part of the Moderna trial for adolescents in Banning, Calif.

(Lisa Polansky)

Inoculating children is the critical next step in the U.S. vaccination campaign — and one that public health officials worry could prove difficult because many parents may figure their children are unlikely to become critically ill from the virus and thus will be fine without shots.

This week, Pfizer announced that its vaccine had proven 100% effective at preventing COVID-19 symptoms in a clinical trial for children 12 to 15. Moderna has not said when it expects to have results of its trial involving 3,000 children 12 to 17 — including the Polanskys.

Both companies are also testing their vaccines in younger children, as researchers aim to identify the right dosages for age groups as young as 6 months. Johnson & Johnson plans to do the same.

The Pfizer vaccine is currently authorized for people 16 and older, while 18 is the age requirement for the other vaccines.

A total of 101 million people in the U.S. — or 30% of the population — have received at least one dose of a vaccine. Experts say that figure must reach at least 70% to achieve herd immunity, the point at which the virus begins to die out because too few people are vulnerable to infection.

Achieving that will be nearly impossible without vaccinating significant numbers of people younger than 18, who make up about a fifth of the population.

Many adults have been reluctant to get vaccinated, and because young people are far less likely than adults to become ill with COVID-19 and only rarely die from it, the incentive for parents to vaccinate their children is even lower.

The main concern from a public health perspective is that they might still spread the virus, even if they have no symptoms. In a possible sign of the difficulty of persuading parents, vaccine makers said they struggled to enroll children in their trials.

Families like the Polanskys are the exception. Lewis said he can understand why some parents don’t want “mystery serum” going into their children. But he pointed out that the vaccines have already been proven safe for adults and argued that many teenagers are bigger than many adults.

“We’re both taller than Mom,” he said.

Lewis Polansky, 15, receives an injection at the Moderna trial site in Banning, Calif.

(Lisa Polansky)

Both he and Elsa — and their parents — view participation in the trial as a public service that will help them return to normal life. But the teenagers also acknowledged that they were drawn by another perk for enrolling in the trial: payments totaling about $1,600.

“All our friends are really jealous,” Elsa said. “I’ve spent a lot of it already — but honestly, I’m not sure how.”

Lewis said he purchased computer chips and engineering parts to build a semiautonomous plane, plus some supplies for a cybersecurity youth organization he runs.

They are among several children in the South Pasadena area enrolled in the Moderna trial and whose families know each other — and call themselves “the trial posse.”

One parent, Saida Staudenmaier, said the decision was “a no-brainer.” Though COVID-19 is mild in most young people, she worried what an infection could mean for developing young bodies in the long term.

For her children — 16-year-old Hannah and 13-year-old Otto — it was more about the hope of escaping the isolation wrought by the pandemic.

Otto’s dance classes have often been pre-recorded. Hannah’s Girl Scouts meetings are online. Her advanced-placement biology teacher recently reminded Saida that she’s never met Hannah in person and only knows her through a two-inch box on her computer screen.

After their second shots, Hannah and Otto were both draped over the couch with headaches, fevers and other flu-like symptoms. They concluded that they were not in the placebo group.

Hannah rolled over, miserable, and said to her mother: “Wow, I’m so, so happy.”

Otto now plans to attend Boy Scouts summer camp in Oregon, and Hannah will tour colleges up the Northern California coast.

Hannah Staudenmaier, 16, receives an injection during the Moderna trial for children ages 12 to 17 in Banning, Calif.

(Eric Staudenmaier)

For 15-year-old Aubry Deetjen and her family, the stakes felt more dire. With an immunocompromised father, she committed early on in the pandemic to help create an “immunity bubble” around him. She hasn’t seen most of her friends in person in months — not even outside.

When her 18-year-old brother enrolled in the adult trial for Novavax’s COVID-19 vaccine, she asked her parents for permission to join the Moderna trial. Her mother, Lisa Henderson, agreed — and helped recruit about 25 other children to join as well.

“We have an open discourse about a lot of things in our house,” she said. “When they’re old enough to talk about these things, they’re old enough to make their own decision. Either way, we’d respect it.”

If school reopens full time in the fall, Aubry wants to be able to go back without her parents worrying whether she’ll bring the virus home.

In a phone interview, Aubry described the importance of the coronavirus “spike protein,” which she learned during a science unit on RNA-based vaccines.

“Understanding what would be happening in my body if I got the vaccine — that cleared any doubts,” she said.

A dedication to science was a motivating factor for many parents who are giving the authorization for their children to participate.

Bridgid Fennell took part in a varicella vaccine trial as a child in the late 1970s. She said her 11-year-old son, Kieran Fennell-Molinaro, jumped at the chance to volunteer for the pediatric Moderna study. They were eagerly waiting this week to hear from the company whether he will be invited into the trial.

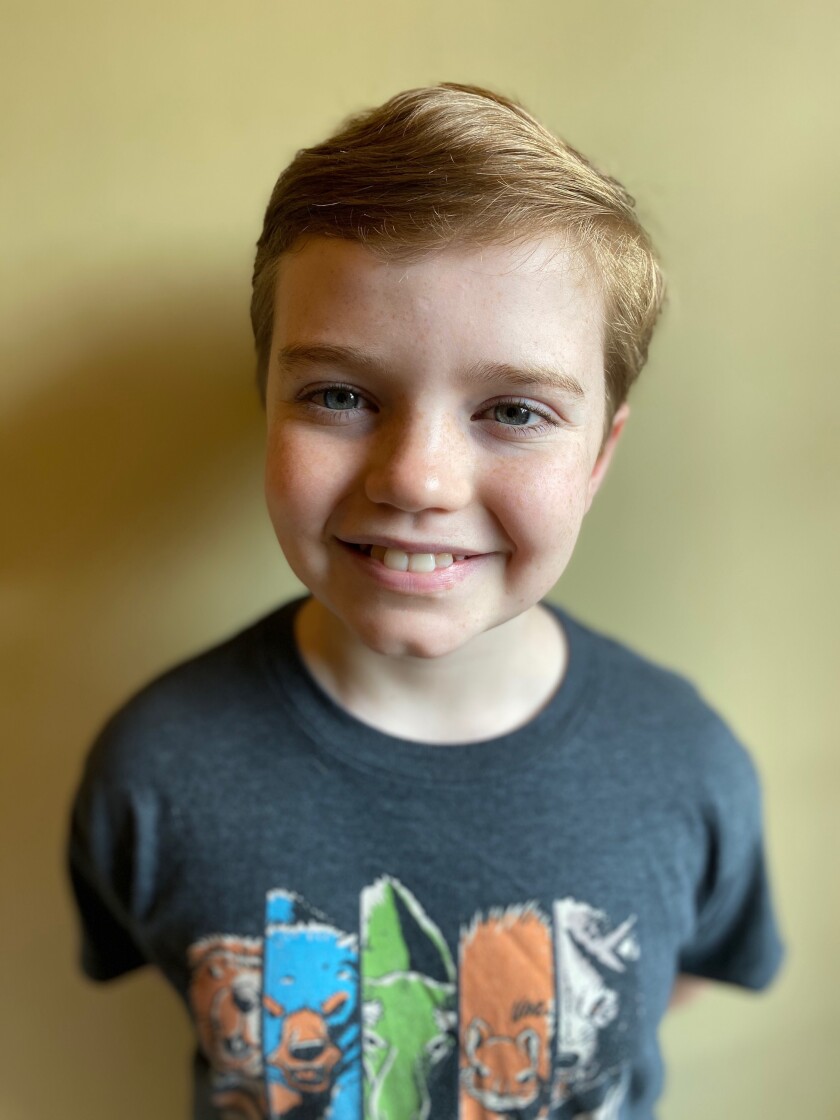

Kieran Fennell-Molinaro, 11, is eagerly awaiting an invitation to participate in the Moderna trial for children.

(Bridgid Fennell)

“This is such a monumental effort, and for him to be a part of it, that’s incredible,” his mother said.

She called Kieran her “little scientist” and said she is “100% onboard,” with no real concerns for his safety — despite warnings on the consent form about the possibility of life-threatening allergic reactions and other side effects. He isn’t worried, either.

“I have to get a shot, which I’m really OK with, and I’ll get asked questions, which is pretty easy,” Kieran explained. “Plus, I know what a placebo is.”