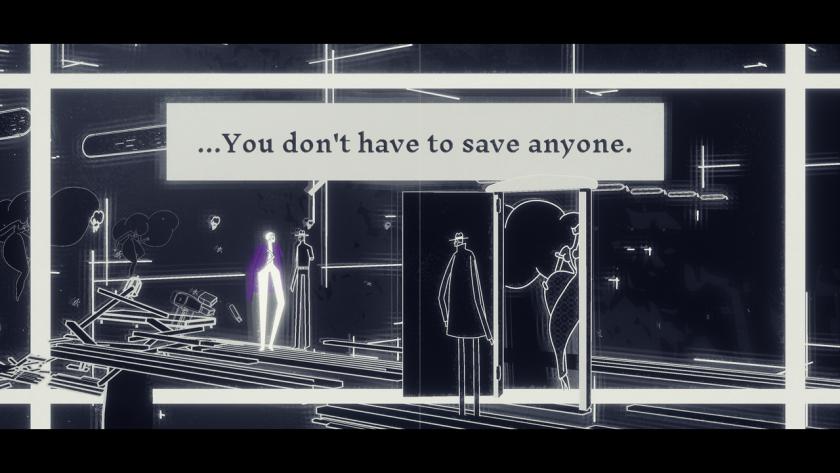

There is a moment late in the game “Genesis Noir,” an abstract work with a hardboiled tone, when the malleably sketched black-and-white scenes suddenly explode in color and sound. Pastel flowers and warm faces fill the screen, and a rush of optimism comes over our cynical protagonist.

A vision of a potential new partner takes his hand, and after a few hours of puzzling together the past, what lies before him and the player — the two of us, essentially — is an imagined future. And then comes what amounts to a record scratch.

The stubborn antihero we had been puppeteering for the past few hours shakes his head and points in the distance. Color? Gone.

What materializes in the darkness to haunt our character’s newfound good fortune is past trauma — what the game, via surreal magical realism and mostly unexpected interactions, had been trying to undo.

“Can we stop it?” asks our new acquaintance, who may be imagined and is suddenly hip to the reality of where this is heading. “No,” says our boy, and all the bizarre and psychedelic imagery of the game suddenly feels tethered to the tragic realities of Earth and every stressful moment prior to the present. But that isn’t the end of the game.

“Genesis Noir” asks us to question how our past shapes us.

(Feral Cat Den)

Every time I hear of how the pandemic has put a strain on relationships — and mine have been no stranger to that — I can’t help but wonder if people should have just been playing more games.

I’m being somewhat flip.

But I’m also completely serious. I’ve long had a fascination with games that deal with love and romance, and when the rare game comes along that tackles such subjects with grace, I find these works to be powerful in the level of introspection they ask of a fully invested player. It’s not akin to a proper therapy session with a real live human, of course, but games by their very nature ask us to partake in a conversation, to interact with a world and consider the implications of our participation.

“Genesis Noir” at this critical point in the game presents us with choices, doors we can open to propel forward into uncomfortable examinations of the past, both our own and those of earlier generations that unconsciously shape a view of the world. We see violence, nasty habits and the falsehoods we tell ourselves about the comfort of routine. In this moment, and here we are simply in control of movement, we are bringing our new friend along on a trip of interpersonal tourism.

Only after we’ve explored the tension between our ability to pretend versus the myth we’ve sold ourselves does “Genesis Noir” offer a diverging path: Take a leap of faith into the unknown or try to rewrite history?

“Genesis Noir” is an interactive metaphor that asks players to think about how the past informs our actions.

(Feral Cat Den)

At this defining scene in ‘Genesis Noir” I set the controller down and let the moment linger. “Genesis Noir,” a playable metaphor, had been asking the same questions all along: How much of our history do we want to hold onto and how much do we long to change? Is it better to torch it all and embrace the joy that is the discomfort in the unfamiliar, as one scene had us do by setting aflame the lead character’s past?

Welcome to a game in which we battle only our own minds.

Early in the pandemic I suffered a breakup with someone dear to me. Then, in January I met someone whose introduction felt like a long-lost connection. She arrived as a reminder that a bond with another human has the power to be a source of constant comfort and calmness simply from the knowledge of her presence in the world. A mere glimpse of her art would instantly put me at ease. Thus, the last year has been a cycle of lows and highs that remains in constant flux, playing tricks on even the most stable of brains.

Yet games such as the personal-fulfillment quest “Journey of the Broken Circle,” the perspective-shifting puzzler “Maquette” and “Genesis Noir” — a game inspired by vintage Italian sci-fi texts that puts our lives and loves in a grander, universal context — have done as much for me in this pandemic year as any of the philosophy books I dug out of an overstuffed closet.

An entire relationship becomes a miniature world in “Maquette.”

(Graceful Decay / Annapurna)

This isn’t a new phenomenon. The novel-like “Florence,” which came out in 2018, explores the mind games of routine; the depression blanket of “Apartment: A Separated Place” tracks the healing journey from nightmare to dream state; “Cibele” deals with intimacy and commitment in an era when a crush is often established via the performative world of the internet; and “Sayonara Wild Hearts” remains a masterful achievement in balancing burning passion, the healing power of music and personal growth, all in a fast-moving, rhythm-based experience.

What strikes me as different about “Journey of the Broken Circle,” “Maquette,” “Genesis Noir” and even at times the wacky divorce-focused platform game “It Takes Two” is how each indirectly feels made for this late-pandemic cultural moment. With the exception of “It Takes Two,” stories and plots, while present, are left relatively open to interpretation, as the games seek not to become visual novels but to create a sense of negative space for the player to occupy.

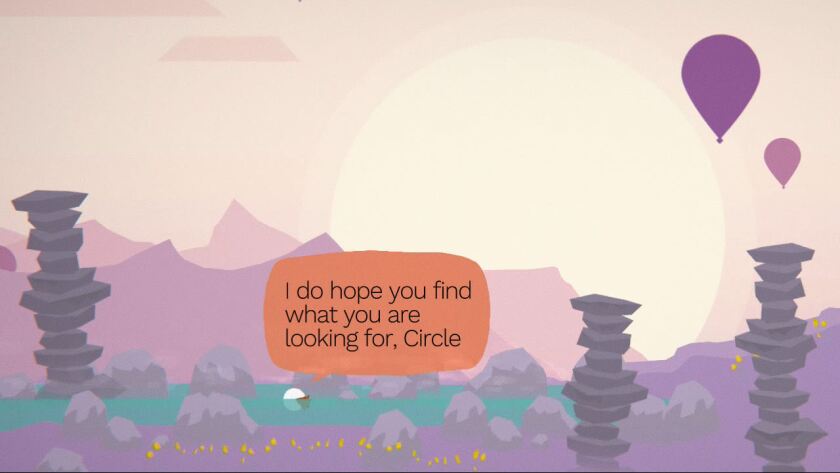

They’re conversation starters built for contemplation. “Journey of the Broken Circle” uses only shapes, animals and objects, often dispensing centuries-old wisdom to our lonely circle, which has a Pac-Man-like pizza slice missing from its shape. “Most pursue pleasure with breathless haste that they hurry past it,” says an owl, while a balloon makes like philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and offers a lesson on the difference between subjective and objective truth.

“Journey of the Broken Circle” is a self-actualization quest.

(Lovable Hat Cult / Nakana.io)

We encounter these characters in what is mostly a traditional platformer — we roll, jump and bounce around various obstacles amid landscapes of painted nature. In this setting, our almost-round ring embarks on a journey of self-actualization, looking for a place to call home and maybe a partner to share it with.

But it’s really about understanding the difference between being broken and surviving, and learning how to let go of the idea of being whole, an all-consuming obsession for our poor circle — so much so that as it bounds around the world the shape overlooks the relationships it’s failing to form. At a time when many of us have spent the bulk of the year divorced from friends, family and co-workers, and have struggled to maintain or foster new connections, a game about recognizing the triumph of survival felt like it was extending a hand.

Particularly noteworthy, however, is that these aren’t stories that heighten trauma or conflict, even when those are present. In an effort to erase the idea of a so-called good or bad choice, “Journey of the Broken Circle” and “Genesis Noir” double down on environments that lead to deep thinking rather than dramatic set pieces. Atmosphere takes precedence over dialogue.

There are times in “Genesis Noir” in which we plant seeds or reconstruct Athenian-inspired narrative pottery, or, in its best moments, swipe a cursor to improvise in a jazz combo. It’s all an effort to connect with nature and the past, but none of these is particularly tricky.

What makes “Genesis Noir” engrossing is that each new setting asks us to relearn how to communicate with the game — what action, for instance, does a button press lead to? We are in constant dialogue, embarking on a guided path that provides an illusion of being a story director but still gives us an active role that invites us to fill in the blanks with our own experiences.

If “Journey of the Broken Circle” or the puzzle game “Maquette” were films, for instance, nothing much would happen. Yet the medium of interactivity allows for constant momentum, allowing us to not just luxuriate in the mundane — or, you know, what should be considered normal — but to live inside a metaphor that can transform the ordinary into the magically abstract.

The San Francisco-influenced worlds of “Maquette” are said to be inspired by a couple’s shared drawings. For those who value romance and creatively equally, “Maquette” can hit hard.

(Graceful Decay / Annapurna)

“Maquette” is a beautiful game but also a heartbreaking one. I struggled to finish it, and not because its viewpoint-dependent puzzles are sometimes complex, asking us to rethink the emotions associated with various colors or to imagine how simple objects such as a key can be used in unintentional ways. As fantastical as it can appear when we shrink a multistory metal ticket to the size of an ant or turn a key into a bridge, “Maquette” never fails to feel honest.

It should be noted that the voice work of real-life couple Bryce Dallas Howard (“Jurassic World,” two-episode director of “The Mandalorian”) and Seth Gabel (“Salem,” “Fringe”) laces the game with a sadness that comes across as alternately intimate, comforting and achingly familiar. The corny, couple-only jokes draw us into a world that looks constructed out of paper, a San Francisco that never was, one filled with dreams and heartache. We visit secret childhood hiding spaces, parks and awkward parties, and experience the course of an entire relationship. Yet the architecture is constantly idealized, a neighborhood of temples and palaces dedicated to the sacredness of our memories.

“Maquette” hit particularly close to home.

Its relationship is ordinary in its lack of spectacle but also peppered with the sort of believable details that make it feel universal. Its emotional tone, primarily one of missing someone, is easy to relate to. Additionally, the conceit of the game is centered around the personal art a couple made together in a shared notebook. For those who, like myself, prioritize romantic partnerships fueled by the creative sharing of art and ideas, expect quite a bit of tears.

And yet this set-up is what allows “Maquette” to be affecting.

The game unfolds as a treatise on what a couple imagines, both when they’re together and when they’re apart, and how those images can be in conflict. There’s love, but there’s also a fear of a loss of autonomy. The cliché that absence makes the heart grow fonder is one I’ve struggled with, as I’ve found that for an introvert it more often leads to overthinking and decisions we come to regret. “Maquette” encourages severe analysis but its mood is reflective and wistful. The game is based on zeroing in on objects and contemplating what they can represent when seen from another angle.

There’s sorrow in “Maquette,” but I wish I had played it with a prospective partner. Even as a work designed to explore heartache, the game asks us to think less about what we know and more about what could possibly be.

Of course, your mileage may vary. Since the games mentioned here generally downplay plot, they are filled with vacant space that surrounds a few key prompts and cues. How we choose to fill that is relatively private.

For me, throughout “Genesis Noir” I was inspired to think of how past experiences influence current expectations. “Journey of the Broken Circle” brought up my anxieties surrounding commitment and worries over what I give up. “Maquette” is a celebration of little moments between a couple and a prod to share more with the people we love — or those we think we may be capable of loving.

I would never say games can cure a broken heart, nor do I believe such a thing is fully possible after one has survived a certain amount of life and romantic grief. But self-reflection doesn’t have to be homework or scary. It can simply be playful. For when we play, we’re choosing to be free of everything but the moment we are in.

And they say love shouldn’t be a game.

“Journey of the Broken Circle”