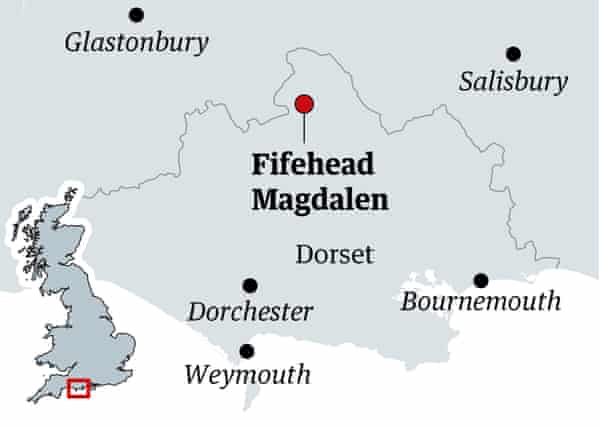

My bike has mostly been unused this winter. In me at least, lockdown inspired a need to walk rather than cycle, but today I took a short ride through the lanes of north Dorset to the village of Fifehead Magdalen.

The early April sun was weak, the trees budding later than I would like, but it was time to be out. This is the Blackmore Vale – thousands of acres of farmland devoted mostly to cattle, bounded by hills on three sides. It’s also Thomas Hardy’s Vale of the Little Dairies: Tess of the d’Urbervilles opens in the village of Marnhull (Marlott, he renamed it) and Shaftesbury, perched on a nearby hill, became Shaston, home to the doomed and obscure Jude.

It’s perfect territory for the unpractised cyclist – mostly flat, narrow lanes winding through a patchwork of small, high-hedged fields, dotted with veteran oaks, survivors of the royal hunting forest of Selwood. Brooks and streams empty into the River Stour. The vale has a stubborn beauty, but it’s practically unknown, much less visited than Dorset’s glamorous Jurassic Coast or the Purbeck Hills to the south.

Shillingstone Hill, Melbury Beacon and the iron age hillforts of Hambledon and Hod loomed above me. A decade after moving here, I’m still finding new roads to explore, and today was like that. This was a meander, unrushed. The recently cut hedgerows were brightened by splashes of white blackthorn flowers. I felt I was reaching back into the past – something about this place encourages wistful thinking, nostalgia’s strange and unreliable pull. I stopped to check my map – I had planned to ride or push the bike along part of the Stour Valley Way, a footpath that runs along the banks of the river, but I missed it and instead made the easy climb to Fifehead on the narrow road, crossing the Stour where makes a leisurely diversion south of the village.

Fifehead is only a few minutes ride from the A30 but feels remote. It’s ancient – William the Conqueror, carving up his new kingdom for family and friends, gave the village to a noble said to have been his nephew, and his Domesday Book decreed it could support Five Hides (a hide being enough land for one family), hence its name.

I was greeted by rooks calling from nests in high trees, but otherwise it was as quiet as always, a single lane meeting another at the crest of the hill, miles from a pub or post office. It would be easy to call the hamlet “timeless” or “ageless”, but time isn’t standing still here, just as it doesn’t anywhere – recently I had seen signs on the noticeboard protesting against a proposed solar farm.

I’d come to look for what remained, if anything, of a grand house. On the 1919 Ordnance Survey map, Fifehead House is marked clearly, but it’s long gone. It can be hard to find forgotten places, but today it was simply a question of looking for the right signs.

I left the bike next to some fine, padlocked, wrought iron gates, with stone pillars on either side, one still topped with a simple round finial. Beyond was what appeared to be a grassed-over driveway, lined with beech trees, a profusion of daffodils and primroses at their feet. Unable to enter, I wandered up the adjacent church path.

Saint Mary’s was locked – services would not begin again for another week, but on a previous visit I had been bowled over by its beauty – a curved ceiling, a bright, stained-glass window set into the rough stone west wall. I have no affiliation to any faith, but English parish churches’ stripped-back, undemonstrative religion carry a sense of restrained peace, more the weight of long history than of God’s presence. Saint Mary’s has a little side chapel near the altar, devoted to the family who built the mansion that preceded Fifehead House. Set against pale-pink walls, the large and lavish 18th-century memorial commemorated Richard and Frances Newman and their seven children, three of whom died young.

I walked among the shaded graves outside, searching for an easy way into the old grounds. At the edge of the churchyard the land dropped away, retained by a thick wall with a short drop to the ground on the other side. I’m usually not averse to a little, harmless trespass in the cause of discovery, but I didn’t fancy the potent young nettles below, or having to scramble out again.

Why come here at all? Fifehead House was nothing special, really. If I had wanted special, I should have been a few miles further east, where the fabulously wealthy, gifted, eccentric, bisexual and almost certainly insufferable William Beckford built Fonthill Abbey. His home was an enormous gothic folly complete with a 90-metre tower, which collapsed shortly after he sold it in 1822. He’d moved to Bath, where he built another tower which still glowers over the city.

The few pictures of Fifehead House show a comparatively modest three-storey Georgian building, with a smaller wing bolted on. A neatly trimmed lawn and flower border surround a graceful curving drive, presumably running to the now-padlocked gates. Trees brush close to the house. It’s summer in the photographs, the wide and tall sash windows are open. Despite the season, smoke rises from a chimney, maybe for the kitchen. It’s hard not to imagine the crack of croquet balls and an England of stability and peace, but this is illusory.

Between 1900 and the 1970s, hundreds of grand houses disappeared. A long and slow depression had swept the countryside, ruining the agricultural economy – the poor, already robbed of their access to common land by the Enclosure Acts, fled to a sooty alternative in the cities. Their lords – the aristocracy and “Squire-archy”, a practical, unsentimental bunch, mostly – prepared to do whatever was necessary to retain their standing and influence, and began selling their estates and turning their backs on ancestral homes.

The wars came and houses were requisitioned for hospitals, for troops, for training. The great houses were often left irreparably damaged. In the opening chapter of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, Charles Ryder returns to a desecrated Brideshead, prompting a deluge of suppressed memories stretching back to his romance with the aristocratic, alcoholic Sebastian Flyte at Oxford in the 1920s. After city raids, the Luftwaffe would sometimes drop unused bombs on land around Fifehead Magdalen, but they did no damage.

In London, palaces were knocked down. In the countryside, grand houses fell or were substantially reduced. Down and down they came, reduced to rubble or left until they became dangerous, which often was not long.

A little way down the lane I hopped over a style into a field. Sheep and lambs watched me with their usual combination of impassivity and anxious curiosity. A lost-looking sequoia tree, almost without branches but a clear remainder from an estate, stood alone. Trees were arranged in little clumps on the sloping ground, which spoke of design rather than farming practicalities.

The view across the vale was spectacular, taking in the nearby village of Stour Provost and the wooded bulk of Duncliffe, where bluebells would soon emerge. Stock fencing kept out the sheep, and me, but the high, red-brick wall of the old kitchen garden was clearly visible, while the remains of the ha-ha still made a distinct mark on the edge of the field. I found a flat section of land – was this where the house once stood? My guidebooks were mostly silent. The house came down before the first edition of the Dorset Pevsner. Frederick Treves left it out of Highways and Byways in Dorset. Only the 1960s Shell Guide made brief reference to it, saying the house was invisible from the road; by the time the book came out, the house wasn’t visible from anywhere, having been demolished just before publication.

As I returned to my bike, I found a campervan parked in front of the iron gates. A man in middle years, bald, with thick, rimmed glasses and earrings, poked his head out. He worked the farm here, was concerned that a sheep and lamb were wandering loose nearby, but was happy to talk. He told me a local rumour – Fifehead House was demolished because the owner had been a senior figure in MI5, and he preferred a more secluded spot – building a new home deeper in the trees, and with better security.

I was pleased to have found the physical remains of Fifehead House, and someone who knew of its past, but I wondered if the real story had eluded me – was it really one of spooks rather than decay and decline in the rural economy? In any case, on this modest Dorset hill there was something left behind: the trees, the descendants of earlier carefully planted daffodils, the slight undulations in the earth, all hinting at a wider history. These houses may have vanished, but their ghosts left shadows on the landscape.

Jon Woolcott lives in north Dorset and works for Little Toller Books. He is writing a book about the southern counties of England. Follow him on Instagram @dorsetjonw