Glasgow is haunted by itself. Unlike Edinburgh, whose every steeple and gable makes the past feel part of the present, Glasgow is its own ghost.

In this city, which looks much more new than the capital, history is glimpsed from the corner of the eye; it is a shiver on a late-autumn night as darkness falls on Duke Street and the brewery smell fills the air. Glaswegians are chronic nostalgists. We have a pretty straightforward relationship with the past: we just want to live there.

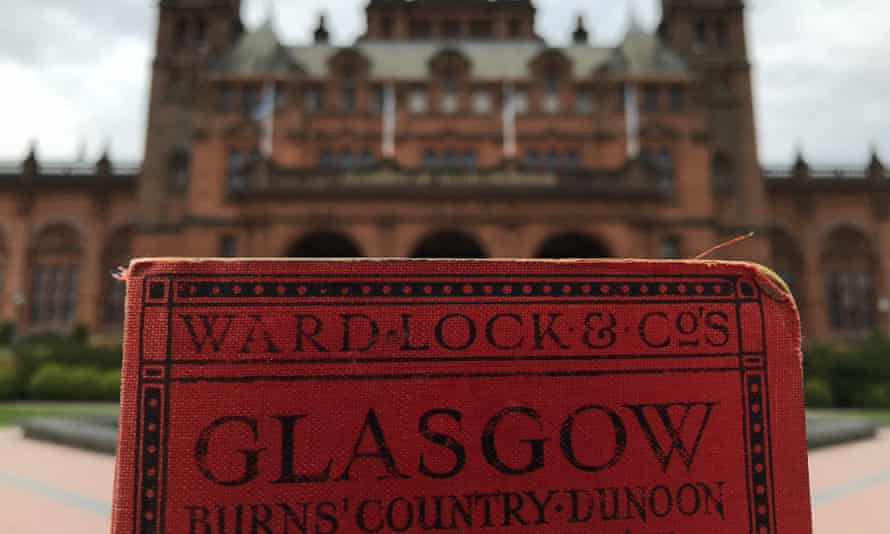

All of which is why I am standing in the Necropolis, the city’s great Victorian cemetery, holding a tourist guide from between the wars. The Ward, Lock & Co guide to Glasgow, the Clyde and Robert Burns country – “with appendices for anglers, golfers and motorists” – is a little red book, published in 1930, with fold-out maps and quaint adverts: “Electric light throughout,” tempts one of the grander hotels. “Hot and cold water in bedrooms.” Ward Lock guides to the UK first became available in the 19th century, when the railways created a tourism boom. They are useful rather than lyrical: their tone is that of a well-informed and cheerful companion who, while keen to stick with the itinerary, knows a decent little place for a cup of tea should refreshment be required.

I love using old books like this one to deepen the pleasure of travelling, so that I am not just visiting a place but a time. I picked up my copy for £3 in a charity shop in Glastonbury, and wondered about who had used it all those decades ago. What drew them north? What sights did they enjoy? I want to see Glasgow as that traveller from Somerset might have seen it, and to see what has changed.

The Necropolis is part of Ward Lock’s suggested plan for a day out in Scotland’s biggest city. For the modern tourist it is a good place to start, as it offers the best view of Glasgow’s medieval cathedral – far more Instagrammable than the one from Cathedral Square. The cemetery itself is a delight for those whose taste runs to tombs. “The most conspicuous monument on the summit,” says the guide, “is that of John Knox in his Geneva cap and gown.”

The statue of the Protestant reformer glowers from the skyline over a town that has little time these days for his fire and brimstone. Down the hill on Queen Street, the statue of the Duke of Wellington on horseback – focus of a folk ritual in which revellers climb up and place a traffic cone on his head – has become a sort of funhouse reflection of Knox. In a black-and-white photo of the equestrian monument in my book, there is no sign of this tradition, but of course that was Glasgow BC: Before Cones.

A particular pleasure of tourism in your own city this year is becoming reacquainted with places reopening after lockdown. I visit Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum on the day it welcomes back the public. This dramatic red sandstone palace is so much a part of the cheery, bohemian ambience of Glasgow’s West End that it gives the impression of always having been there, yet in 1930 it was still a newish building with a growing collection.

My 1930 guide recommends going to see Rembrandt’s A Man In Armour, which I do, but I also make a pilgrimage to Salvador Dalí’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross. A controversial acquisition in 1952, it is now considered a masterpiece and an honorary Glaswegian in its own right. Visiting it is like seeing an old friend. May it never hang in a gallery empty of people for so long again.

Ward Lock suggests getting around by tram, but these were discontinued in 1962, so there seems little point waiting for one. Instead, I stroll along gorgeous tree-lined Kelvin Way. Closed to traffic since the start of the pandemic, it is so quiet I can hear a woodpecker busy in the trees. Glasgow is known as the “dear green place” on account of its many public parks, among which Kelvingrove is arguably the most popular. My guidebook quotes a 19th-century song – “Let us haste to Kelvin Grove, bonnie lassie, O” – as evidence of its enduring popularity, and Glaswegians have continued to hasten there in the decades since, often with a “kerry-oot” despite a ban on outdoor consumption of alcohol since 2008.

I must make haste myself to the next landmark picked out by the book. “The Mitchell Library … opened in 1911,” the guide informs. “It is the largest free library in Scotland.” I am especially fond of the Mitchell, in particular its psychedelic carpets, around which a cult has grown. Those were laid in the 1980s, so would have been unknown to Ward Lock.

However, the traveller from Somerset who owned my book would have had the pleasure of admiring its great verdigris dome. This rhapsody in green is emblematic of Glaswegian romanticism. Upon seeing this illuminated at night, many citizens have our own version of Woody Allen’s opening monologue from Manhattan playing in our heads. We idolise Old Glasgow out of all proportion.

“People love stories about how the city used to be, but don’t look at how it is now,” says the writer Denise Mina, whose novel The Long Drop captured the dirty old town of the 1950s. “People talk as if they’re ex-patriates of the city in which they still live.”

Why do we find the past so seductive? Norry Wilson, who runs the popular Lost Glasgow social media accounts, believes it is the yearning pleasure of the just-out-of-reach: “So much of the old city is gone. The middle of the picture is missing.” Vast areas were cleared in the 1960s and 70s to make way for the M8 and high-rise flats, so anyone wanting to experience the city of yesteryear must do so with the help of vintage books and photographs, and whatever clues remain in the built environment.

“Glasgow Endures” reads a homemade banner across the front of one such clue: a grand Edwardian apartment block overlooking the motorway. The sign refers to the ability of the citizenry to suffer and survive anything, including Covid-19, but what truly endures is the Glaswegian spirit: that distinctive mix of fatalism and irreverence.

My last stop is Queen’s Park on the south side. It’s in the increasingly hipster-ish district of Govanhill, which in 1930, as now, was the first port of call for immigrants to the city. A walk around these streets offers a banquet of aromas from the takeaway food of many nations and cultures. In the park, plumes of barbecue smoke perfume the early-evening air, and a woman plays clarinet beneath an oak. Queen’s Park is on a hill, and the climb, according to Ward Lock, “may be regarded as a gentle preliminary in Scottish mountaineering, but the extensive view from the summit repays the trouble”.

The panorama is indeed worth the puff: far fewer factory chimneys than in 1930, but still many steeples. Glasgow Cathedral is visible three miles north and, next to it, with a little help from binoculars, the statue of John Knox where, earlier, my journey through this phantom city began. The stone preacher, high on his graveyard plinth, looks out across a city much changed, but still hauntingly beautiful.

Peter Ross’s latest book is A Tomb With A View: The Stories & Glories Of Graveyards (Headline, £20)