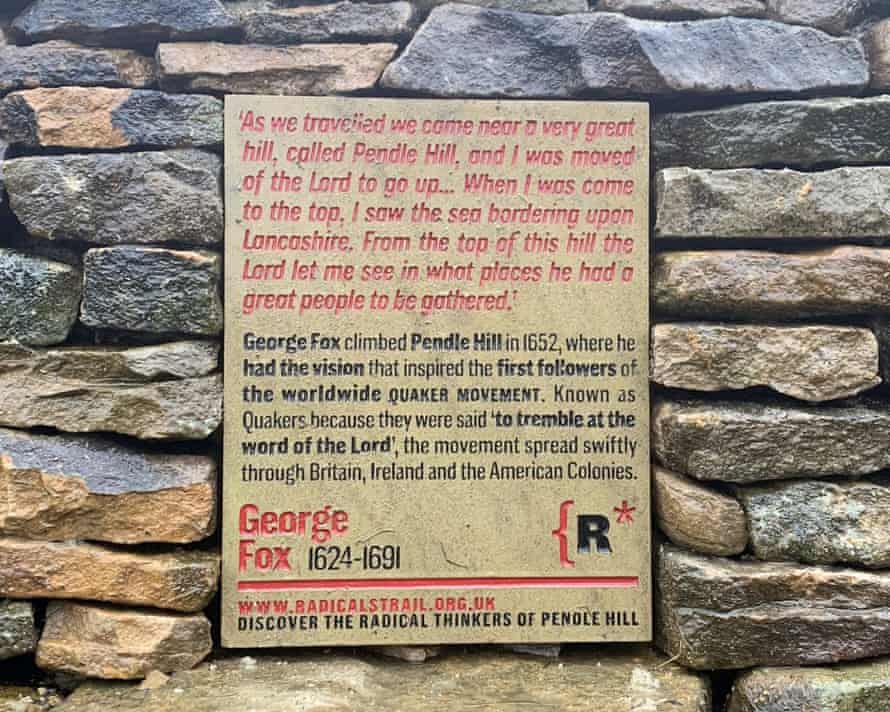

When he climbed to the top of Pendle Hill in 1652, dissenter George Fox had a life-altering vision of the world calling for “a great people to be gathered”. Fox went on to found the Quakers. Most people are happy if they can see Blackpool Tower.

On the Saturday I made it up there, banks of cloud to the west obscured the sea, but you could see all over North Yorkshire, as well as to Burnley and Colne and across to the wind farms of Ovenden Moor.

Pendle Hill is one of the most beautiful lumps of rock in the British Isles. This will be stating the obvious to locals and regular visitors, but it’s worth putting on record, because, despite being born in Lancashire more than five decades ago, I’d never been up the hill until the recent May bank holiday.

Why? Well, perhaps because I’m from south Lancs – the bit that got nicked by Cheshire in 1974 – and to us plains kids, Pendle Hill was a kind of mythical place, oft-mentioned, sort of familiar, spookily inhabited by witches. Yes, it was broadly on the radar, but it was up there, beyond. We went to north Wales, Southport, York, Bridlington for recreation. We went to the Lakes for hills.

In the 1990s I lived on the West Riding and drove past the hill on numerous occasions. Though just 557 metres tall and covering only a couple of miles across, it stands proud and prominent. An outlier from the main Pennine spine, it has no near neighbours, nothing to steal its thunder. I can remember driving from my home at the time, in Hebden Bridge, to work in Nelson, and thinking: one day I’ll take in the view from that strange, lonely, moody-looking hill.

Life interrupted the plan. I went to the Andes, Kamchatka, New Zealand, Scotland for my summits. But, 37 years after leaving Lancashire, I got myself up there at last.

I parked and then walked up to a spot my OS map called the “Big End”. It being a bank holiday, I had plenty of company – from walkers with their gizmos and multicoloured leggings to daytrippers in jeans and T-shirts, out for a breather. They came from the towns at the foot of the hill, and from Preston and Manchester.

I took the north-facing stairway, rather than the gentle incline. Pendle Hill is no mountain but, even Fox, not a man easily overwhelmed, said he climbed it “with difficulty, it was so very steep and high”. He was motivated by the Lord. I had only a flask and some sandwiches, which I enjoyed in the lee of a dry-stone wall at the top. Beyond the Big End is a wide, exposed moor with a track across its peaty middle. I crossed this to a chorus of skittish skylarks, fluttering like chimeras made from dragonflies and bats, singing their chatty song.

Big white clouds scudded overhead, and fraying, ragged grey ones suggested heavy showers over on the Three Peaks, but the rain held off. Later, after I’d descended, the whole hill would be lost under a deluge.

Two years ago, a group of local organisations came together to establish a Quaker Trail around Pendle Hill. The idea was to commemorate the achievements of George Fox, but also to place him and the location in a much wider story about radical thinkers and rebels. Under the banner of Pendle Radicals, seven stops have so far been identified, which people can visit to get an education and inspiration.

“There is not one route or circuit,” says Nick Hunt, creative director at Burnley-based Mid Pennine Arts, one of the organisations involved. “This is more like a treasure hunt, or a state of mind. We want to encourage people to explore, and to find out more about these extraordinary people.

“We are in the midst of installing interpretation at these first sites, but the longer-term plan is to add another half dozen, we hope during 2022,” says Hunt, adding: “Our volunteer researchers are also developing a suite of themed walks, Walking with Radicals, which will be available as downloads.”

A Wonder Women walk will link suffragist Selina Cooper with the mother of the Independent Labour party, Katharine Bruce Glasier. The Two Toms will link pioneers of access to the countryside, Tom Criddle Stephenson, credited with creating the Pennine Way, and Rev Thomas Arthur Leonard, who played a leading role in the Youth Hostels Association, Ramblers and Holiday Fellowship.

In May 2019, author Tracy Chevalier, who was brought up a Quaker, climbed Pendle Hill to promote the Quaker Trail. The pandemic stymied moves to get the general public interested, but things are now back on track. At the end of March, an online meeting – In the Footsteps of Ordinary People – kept up momentum. On this SoundCloud link you can replay the discussion and see two short films about Chevalier’s visit and the Quakers.

I’m going to join in these projects, not least because it will help place the more obvious Pendle Hill theme – the witch trials, which are alluded to all around the hill – in their proper context: the imprisonment, interrogation and probable torture of peasant women by the authorities on behalf of James I. They can only really be understood against the backdrop of the persecution of recusants. Lancashire, along with Cumbria and Yorkshire, was considered a hotbed of religious rebels.

I’m also joining because I’ve relocated to the Ribble valley, and wake up to a view of Pendle Hill every day. Lancashire got me back in the end and, if I can’t claim a Fox-like vision, there is a subtle, linguistic connection between roots and radicals – and between Quakers and all things local. I shall climb to the Big End as often as I can, and see what messages the wondrous horizons send me.

The story of Pendle Hill’s radicals seems to have as many layers as its millstone grit core. In 1842, more than 2,500 Chartists gathered there to call for the extension of voting rights to working men. Bomb Culture author Jeff Nuttall was born in Clitheroe and played jazz in the 90s at Earby, in the shadow of the hill. Experimental theatre company Welfare State International did a six-year stint in the area in the 70s.

Today, groups such as Pendle Folk and the Pendle Hill Landscape Partnership are working to link political, ecological, agricultural and other narratives to develop a new, environmentally conscious kind of radicalism. The openness of high places opens minds. The contours of north Lancashire stimulate our imaginations.

It’s all almost as exhilarating as walking into a fresh gale, as I did at the end of that first short hike. Even the peewits at the bottom of the hill seemed stunned by the sudden gusts. Down in Barley, the village closest to Pendle, returning walkers were having alfresco pints and lunches at the newly reopened pubs. The umbrellas were flapping about even more wildly than the peewits.