I set off on my dream journey from London to Beijing in the halcyon days of 2019. It’s a trip that seems unimaginable today. Travelling overland, I wanted to experience the transitions between cultures, to understand more about what connects us. I was also interested to see the legacy of exchange along the Silk Road trade routes that once connected China with the west.

My first major stop was Venice. The city is full of influences brought there by its many and varied visitors, especially those from the east. You can see these in the domes of Saint Mark’s Cathedral, which evoke the medieval minarets of Cairo, and in Renaissance masterpieces with their brilliant blue pigments – produced from lapis lazuli mined 4,000 miles away in northern Afghanistan and brought to Venice along the Silk Road.

From Venice, I crossed the Adriatic to Pula and rented a car to travel south-east along Croatia’s Dalmatian coast to Montenegro via Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was in Mostar that I first heard the azan, the Muslim call to prayer. The domes and minarets of Ottoman-era mosques perforate the town’s skyline.

To reach Istanbul, I zigzagged across the Balkans on three consecutive 10-hour train journeys. The first of these –from Podgorica to Belgrade – crosses 435 bridges and goes through 254 tunnels.

Old men playing cards, young girls feeding the gulls, fishers awaiting a catch, women walking arm in arm, dogs and cats wandering the streets. There is so much life to Istanbul, so much to drink in.

After a crossing the Bosphorus into Asia, I enlisted the services of East Turkey Tours, which ferried me the length of Turkey: past the resting place of the Islamic mystic Rumi in Konya, through the lunar landscape of Cappadocia, along the Syrian border, around Mount Ararat and finally to the Iranian border. Along the way, we passed caravanserai dating from the 13th century. These were the original travel lodges, where Silk Road traders would rest, wash, pray, share gossip and quarantine before entering cities lest they carry the plague.

Given diplomatic tensions in the strait of Hormuz at the time, I was anxious about entering Iran. My fears, however, were soon allayed by the easy air of my friendly guide.

We drove across Iran in 20 days, passing throughTabriz, home to one of the largest covered bazaars in the world; Isfahan and its mesmerising mosques; the Lut desert, one of the hottest places on Earth; and the holy city of Mashhad, where visitors come for the tomb of Imam Reza. Its golden dome is blinding in the midday sun. Thousands of pilgrims pray in the large courtyards that surround it. Women in black chadors openly weep at the sight of the shrine, whispering prayers while men tenderly kiss the doorways leading to it. My guide, a local mullah, closed the tour by reciting a verse from the Qur’an while a man on a nearby megaphone lamented the martyrdom of the fifth imam, Baqir. Next came Turkmenistan.

Eight of us – Turkmens, Iranians, an Uzbek and me – boarded a banged-up bus and drove to the middle of a bridge separating Iran and Turkmenistan. Here, we were told to get off and wait. Several minutes later a minibus approached from the Turkmen side to pick us up. It felt like a spy-swap routine from the movies.

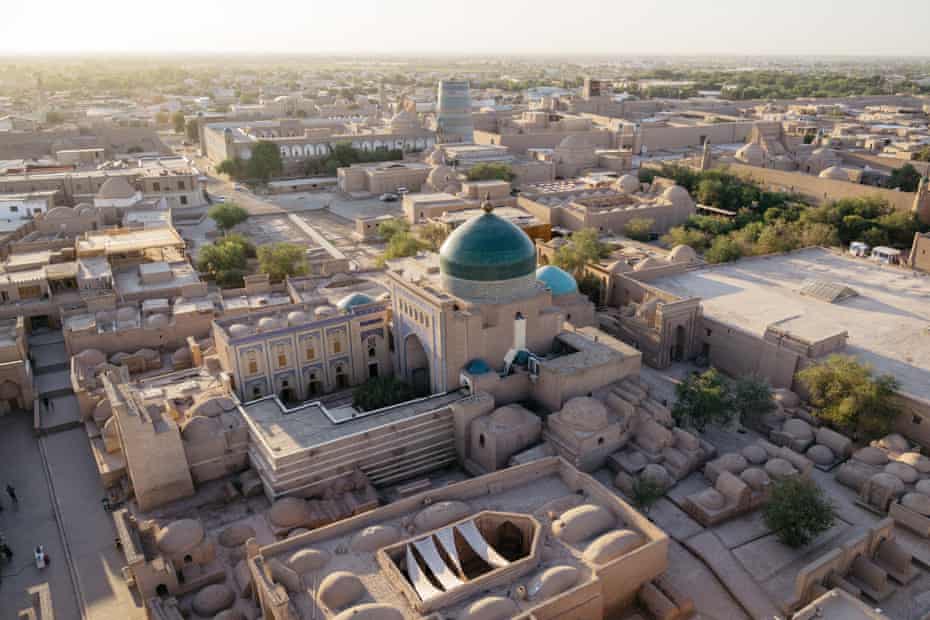

My journey through Turkmenistan took me from the ancient city of Merv to the otherworldly white-marble-clad capital city of Ashgabat, across the Karakum desert and on to the Uzbek border. Emerging from the desert, Khiva is the Silk Road city of your imagination, a treasure trove of palaces, mosques and madrasahs clad in blue tilework that glows in the evening light.

-

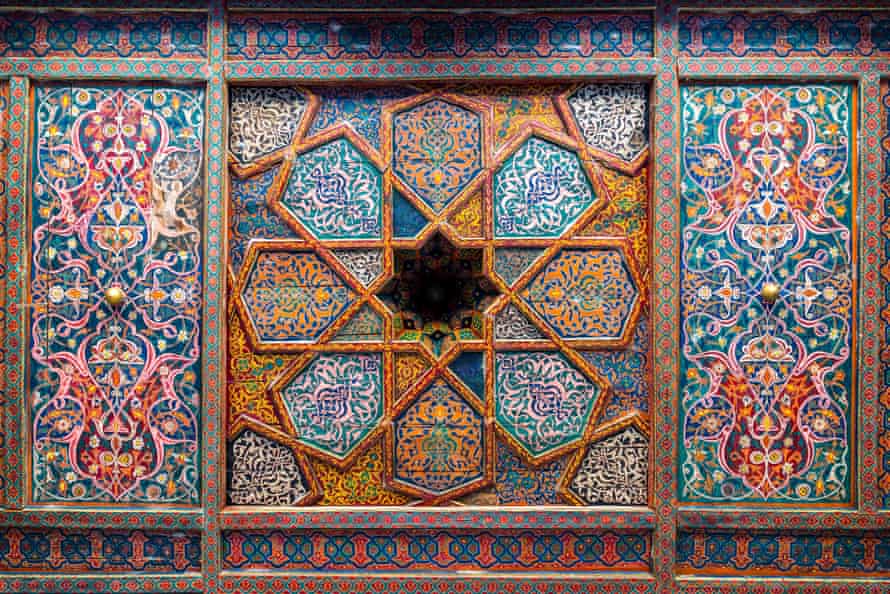

Khiva, Uzbekistan, where blue tiles cover many of the city’s palaces: ceiling details at Tash Hauli Palace

About 300 people were waiting to cross the Uzbek-Kyrgyz border. I estimated a six-hour wait. But, as elsewhere in Central Asia, as soon as I – a tourist – was spotted I was sent to the front of the queue – a level of hospitality I did not feel worthy of. Unlike arid Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan is mountainous, lush and green, a nation of vast, gentle and sweeping valleys. The white yurts of semi-nomadic communities dot these landscapes, as do their herds of horses, yak and camels. The sense of space, under the huge dome ofblue sky, is profound.

To reach Tajikistan, I took the Kyzyl-Art pass. My driver took me to the military checkpoint and waved me off. I didn’t know there was 12 miles of no man’s land between the borders, connected by a rocky mountain road that would rise to 4,200 metres. After dragging my bags for several miles and warding off an aggressive mountain dog, I hitched a ride with two German motorcyclists to reach the Tajik side.

The far east of Tajikistan is dry, dusty and lunar-like. The air is thin. A short walk had me gasping for breath. Unlike the rockier Pamirs to the west, which burst out of the Earth’s surface in dark browns and deep ochres, the mountains here look soft and glow purple, pink and blue. I arranged a guide to take me to the top of Peak Khorog, from where I could see Afghanistan across the Panj River. I had hoped to cross the border and then travel a short distance to Pakistan, but my proposed trip was restricted on security grounds. Instead, I had to take a several thousand-mile detour via the Tajik capital, Dushanbe, and Dubai!

Once I reached Pakistan’s mountainous north, I rested for a few days at the Khaplu Palace. Restored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and converted into a heritage hotel, the palace bears the influences – Tibetan, Kashmiri, Ladakhi, Balti, and Central Asian – of the regions it borders. There are few better places to take in the grandeur of the Himalayan and Karakoram mountains.

-

Built in 1840, the Khaplu Palace is the finest surviving example of a royal residence in Baltistan, northern Pakistan

The journey to Gilgit took me through Deosai, a vast national park at up to 4,114 metres above sea level. After a steep climb, the road opens up into a verdantplateau of wild flowers, gentle rivers and crystal-clear streams, surrounded by snowcapped mountains. In the distance, I caught sight of Kashmiri nomads with herds of cattle and goats.

After many miles of rocky roads, I reached the Karakoram Highway – the main artery connecting Pakistan with China. My traumatised spine was grateful to be back on smooth Tarmac. On the opposite side valley I could see a thin road hanging off the side of the mountain – an original tract of the Silk Road. The owner of the hotel I stayed in recalled seeing merchants on horses and camels carrying silk and other goods using this road before the Karakoram Highway was built.

Past Hunza and the Baltit Fort, which dates from the eighth century, lay the Chinese border. The last stop was the remote frontier town of Sost. Shops, homes and hotels line its main street like in an old western town. Billboards proclaimed Pakistan-China friendship: “Brotherhood is affectionate and diplomacy is eternal,” read one.

From Sost it was five hours by minibus to the Khunjerab Pass – the highest paved border crossing in the world. I sat hunched in the front seat with an old man wearing a traditional Pakol hat. I shared my stash of dry apricots with him. At nearly 4,700 metres, the Chinese border came into view in the shape of a giant marble-clad gateway festooned with billowing five-starred red flags. In this remote wilderness on the roof of the world, nothing could have been more incongruous.

Few places conjure up the myths and legends of the Silk Road like Kashgar. On the western edge of Xinjiang province, the town was the gateway for Chinese traders heading for the markets of central Asia and an essential stopover for those travelling in the opposite direction. The legacy of this mercantile exchange is a strikingly diverse population. There are more than 30 nationalities in the Kashgar area but the region’s diversity is under threat. In April British MPs voted to declare that human rights abuses committed by the Chinese state against the Uyghur people in Xinjiang amounts to genocide.

Near the centre of town, I spotted the old man I had sat with in the minibus: he was selling antiques from his suitcase to a Uyghur shopkeeper. You could tell they knew each other well but they communicated only in hand gestures. It dawned on me that he was still going back and forth across the border and selling wares in the same way they had been doing along the Silk Road for thousands of years. When the bartering had finished, I tapped him on the shoulder. He stared at me for a moment, and then his face broke into a grin and he bear-hugged me.

My next stop was Ürümqi, an 18-hour train ride away along the northern edge of the Taklamakan desert. The word Taklamakan translates as “what goes in does not come out”. Many have lost their lives attempting to cross it but those days are mostly in the past. My train, though slow-moving, delivered me safely to my destination.

Where the Taklamakan desert ends, the Gobi desert begins. I was now on the final stretch of my journey, hurtling east on China’s high-speed rail network. It took about 10 days to cross China and reach Beijing. Over four months, I had travelled 25,000 miles by car, bus, train, boat, horse, camel and, yes, two flights, across 16 countries. My dream of crossing Eurasia was fulfilled. I had 50,000 photos to edit and an exhibition to develop. That exhibition is now open. I hope you enjoy the journey.

The Silk Road: A Living History, an open-air photography exhibition by Christopher Wilton-Steer and presented by the Aga Khan Foundation, is open at Granary Square, King’s Cross, London, until 16 June 2021