It’s 11pm but the sky is still light. In late May, this far north, night hardly happens. We peer out of the back window into the glen. The deer are closer. An hour ago, I spied their silhouettes descending the distant slopes, like tiny antlered beetles. Now they have crossed the river and are advancing over the bog towards us, nibbling as they go.

A young stag stops to stare. Has he seen us? With the house lights out, I’d hoped we were invisible. There’s a long pause, measured by the incessant chiming of a cuckoo and the unearthly thrumming of snipe overhead. Right now, our isolation feels complete. Eventually, the stag lowers his head to resume nibbling. We breathe again.

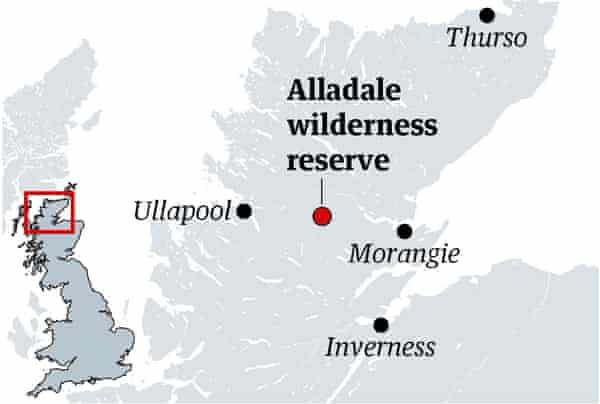

Isolation here is more than just a feeling. Deanich Lodge, where my wife and I are holed up, is among Britain’s most remote holiday houses. Flanked by the imposing slopes of Glen Beag, within the 9,300-hectare Alladale wilderness reserve an hour’s drive north of Inverness, it lies seven miles along a bumpy track from Alladale Lodge – the grand pile where top-end visitors find pricier accommodation.

From the surrounding hills, Deanich appears incongruously tiny: a Monopoly house dropped into the wilderness. Between its sturdy walls, however, this former hunting lodge is a spacious self-catering retreat: with bunkrooms upstairs, it can accommodate up to 18. Central heating and a fully equipped kitchen suggest things have moved on since Victorian times, when former owner Charles Ross reputedly shot a stag from his bath, but visitors should still not expect wifi or a phone signal.

Alladale may be familiar to Springwatch fans – it’s one of three locations chosen by the BBC for the current television series (the last episode airs on 8 June, all on iPlayer). While we are enjoying our social isolation at Deanich, presenter Iolo Williams and the team are up the road at the main lodge, filming the likes of black grouse, red squirrels and other wildlife showstoppers for your entertainment.

Long before Springwatch arrived, this rugged slice of Scotland hit the headlines when businessman-turned-conservationist Paul Lister acquired the property in 2003 to plot one of Britain’s most ambitious rewilding projects. He knew that its picture-book landscape of bare hillsides was, in fact, a human contrivance, its native forests felled in ancient times and much of its rich biodiversity – which once included bear, boar and wolf – long since eradicated. He also learned how the Highlands’ most emblematic animal, the red deer, is today also its most problematic. With no predators to keep it in check, the sapling-nibbling monarch of the glen now thrives in such numbers that native forest can never return naturally.

Lister’s vision was to restore the “Great Forest of Caledon”. He would plant native trees, rescue precious peatlands, control deer and eventually reintroduce wolves. Alarm bells rang. Scotland’s last wolf was supposedly shot by Sir Ewen Cameron at Killiecrankie in 1680. And while there is a sound ecological case for returning this much-maligned apex predator to its former homeland, in reality, public fear and landowner concerns for livestock mean that such a scheme seems unfeasible for the foreseeable.

But many other pieces of Alladale’s ecological jigsaw are falling into place. On a 4×4 tour, reserve manager Innes MacNeill points out the swathes of regenerating native forest – Scots pine, birch, alder, willow, rowan – each sited according to its ecology. As we trundle up hill and down glen, he reels off impressive statistics: nearly a million trees planted to date; more than 33km of deer-proof fencing erected; deer numbers reduced to sustainable levels. “Paul hates fences,” he says, “but they’re a means to an end.”

MacNeill, it seems, provides a reality check to some of Lister’s more impatient ambitions. A local boy, reared as a stalker, he oils the wheels with sceptical neighbours. “This is a legacy project,” he tells me, and change takes generations. Nonetheless, he has clearly bought into Lister’s approach, and explains how the land, once valued in terms of stag stalking, salmon catch and grouse shoots, is now worth more for its natural capital, offering ecological gains that, in the long term, will benefit us all. “Trees make trees,” he says. “We’re establishing seed sources that are going to future-proof this country.”

Our tour also takes in other projects: a new aquaponics centre (no rest for Alladale during lockdown) and a captive breeding facility for the endangered Scottish wildcat. We continue past the lodge – where the BBC are busy checking last night’s camera traps for pine marten footage – and tramp through a gorgeous patch of mature Caledonian forest. A tangled understorey of heather and bilberry buttresses the gnarled, moss-festooned trunks of ancient Scots pines. It’s a vision of the past. And, perhaps, the future.

Reaching a thundering waterfall, we stare into the foam. “Just watch,” says MacNeill. On cue, a gleaming fish flings itself from the chaos and lands with a heavy slap, powering into the onrushing current above. Another follows. Then another. It’s a stirring sight – the Atlantic salmon is in decline – and a fitting metaphor for Alladale’s vision: swimming upstream, against the odds, determined to reach its goal.

Lunchtime on our final day finds us on top of Carn Ban, high above Deanich. Our stiff climb has already been rewarded by sightings of Alladale’s resident pair of golden eagles circling overhead, a lolloping mountain hare and ptarmigan whirring away on snow-white wings. Now, in glorious sunshine, unwrapping our cheese rolls feels like uncorking a bottle of bubbly. We pore over the map, identifying suspects from the lineup of summits. To our west, the mountains stretch to the Atlantic, where the Summer Isles shimmer through the haze. To our east lies the Dornoch Firth, gateway to the North Sea. Two coasts for the price of one – and between them, a snow-splashed panorama of jaw-dropping immensity.

A movement on the hillside opposite caught my eye: two red deer belting along a ridge, as though fleeing a predator. For a second, I pictured a pack of wolves in pursuit. Common sense told me this was impossible. But a landscape of this grandeur lets the imagination run wild. And at Alladale, evidently, imagination is getting things done.