Before the text messages threatening to kill his family, Drew Pavlou gathered a small group of students on a busy walkway at the University of Queensland to protest the Chinese government’s repression of Uighur Muslims and crackdown on Hong Kong.

“Hey-hey, ho-ho — Xi Jinping has got to go!”

As he denounced the Communist leader, hundreds of counter-demonstrators massed around a colonnade at the campus in Brisbane, Australia. Some were students from China; others appeared older. They yelled pro-Beijing slogans and played the Chinese national anthem over loudspeakers.

Pavlou, 20, stopped for a moment and smiled, relishing the first protest he’d ever organized.

Things quickly turned violent. A man in the crowd rushed at Pavlou, snatching his megaphone. A second man shoved him. In the ensuing scuffles, one student from Hong Kong was tackled and grabbed by the throat; another had her shirt ripped open.

VIDEO | 00:38

Protest at University of Queensland turns violent

Drew Pavlou, holding the megaphone, is attacked by Chinese Communist Party supporters, July 24, 2019.

The next day, Chinese state media named Pavlou as a leader of the protest, and Xu Jie, Beijing’s consul general in Brisbane, praised the “spontaneous patriotic behavior” of those who attacked Pavlou.

It was an unusual statement for a diplomat, especially considering Xu’s other position: an adjunct professor at the university’s School of Languages and Cultures. His dual roles were an example of the increasingly close ties between Australian universities and China, their biggest source of international students.

The university didn’t chastise Xu for promoting violence. Instead, it defended its relationship with Beijing — and turned on one of its brightest students.

::

Pavlou’s July 2019 protest, and its turbulent aftermath, revealed how China’s economic power had translated into influence in Australia, affecting even what was said and taught at leading research universities.

In an era of dueling superpowers, Australia’s position is particularly vexed: closely allied to the U.S. but economically reliant on China, which buys more than a third of its exports, including vast quantities of iron ore and coal. In recent years China has also underwritten a boom at Australian universities, transforming international education into a $30-billion industry.

Chinese students’ tuition fees now account for one-fifth of the revenues of some top schools, according to a 2019 study by sociologist Salvatore Babones. At the University of Queensland, a leafy campus of sandstone buildings in Australia’s third-largest city, one in every seven students, and some $200 million annually in fees, comes from China.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and then-Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott signed a free trade agreement in Canberra in 2014.

(Rick Rycroft / Associated Press)

Administrators touted the research benefits and basked in growing global prestige. But in 2017, during Pavlou’s freshman year, incidents involving Chinese students at several universities showed how Australian commitments to free speech and liberal democratic principles clashed with Beijing’s desire for total control and its disdain for dissent.

One lecturer was forced to apologize for using teaching materials that listed Taiwan, which China considers part of its territory, as a country. Another was suspended after students objected to a test quoting a Chinese saying that government officials tell the truth only when “they are drunk or careless.”

Outrage over such cases appeared to be orchestrated or supported by Chinese diplomats. Campus groups known as Chinese Students and Scholars Assns. — overseen by the Communist Party and often funded by Chinese embassies and consulates — monitor Chinese students’ activities and mobilize them for nationalist causes, according to human rights groups.

“Universities keep saying they defend free speech and they believe in academic freedom, but in practice they’re not working to defend the institutions, students or staff from this very specific type of threat that emanates from authoritarian governments,” said Elaine Pearson, Australia director at Human Rights Watch. “They’re so dependent on the income from fee-paying students that it’s impacting the way they respond.”

During the 2019 unrest in Hong Kong, pro-Beijing groups at several Australian universities tore down Lennon Walls of colorful sticky notes erected in solidarity with the democracy protesters. Hong Kong students at Australian National University in Canberra, the capital, began covering their faces at rallies, worried they would be photographed and reported to the Chinese Embassy.

Supporters of the Hong Kong democracy movement, wearing masks to conceal their identities, erect a makeshift Lennon Wall at the University of Queensland in August 2019.

(Patrick Hamilton / AFP/Getty Images)

Wu Lebao, a Chinese-born activist who gained asylum in Australia and is a student at ANU, said students from China weaponized campus policies against discrimination by reflexively labeling any criticism of Beijing as racist, which often caused administrators to panic.

“They use Australia’s openness against it,” Wu said.

::

That summer, Pavlou approached leaders of the University of Queensland’s Hong Kong student association, offering to help stage a sit-in.

The grandson of Greek Cypriot immigrants, Pavlou was an academic star — he’d made the dean’s list twice and won a poetry prize while pursuing a triple major in philosophy, history and English literature. He had a history of depression and could be abrasive but was beginning to find his political voice as a social democrat influenced by Bernie Sanders and the teachings of his Catholic high school.

Reading about Beijing’s mass imprisonment of the Uighur minority, he was disgusted by Australia’s response.

University of Queensland students create signs and sticky notes in support of Hong Kong democracy protesters in August 2019.

(Patrick Hamilton / AFP/Getty Images)

“No one on the Australian left was talking about it,” he said. “On the right, the mining titans were going, ‘The trade is so important, we can’t stuff that up.’ Everyone was playing politics while innocent people were suffering. That our largest trading partner had 1 million Muslims in camps — how is that not national news every single day?”

Built like an upturned broom, with a wall of gelled hair atop a slender frame, Pavlou hardly looked like he was spoiling for a fight. On July 24, he showed up a half-hour late to the rally. He was attacked three times, once by a man who struck him from behind in the back of the head, until police dispersed the crowd.

Pavlou wondered whether the consulate had mobilized the opposition, especially after a leader of the pro-Beijing side let slip that some in his group weren’t students. Some had hid their faces behind masks.

Pro-Beijing students gathered at the University of Queensland on July 24, 2019.

(Drew Pavlou)

Hours after the protest, the university said it supported “open, respectful and lawful free speech, including debate about ideas we may not all support or agree with.”

Pavlou was expecting a harsher condemnation of the violence and an investigation into his attackers. The university did not respond even after Australia’s foreign minister rebuked Xu, the Chinese consul general, for encouraging “disruptive or potentially violent behavior.” Campus administrators declined an interview request, and Xu did not respond to messages.

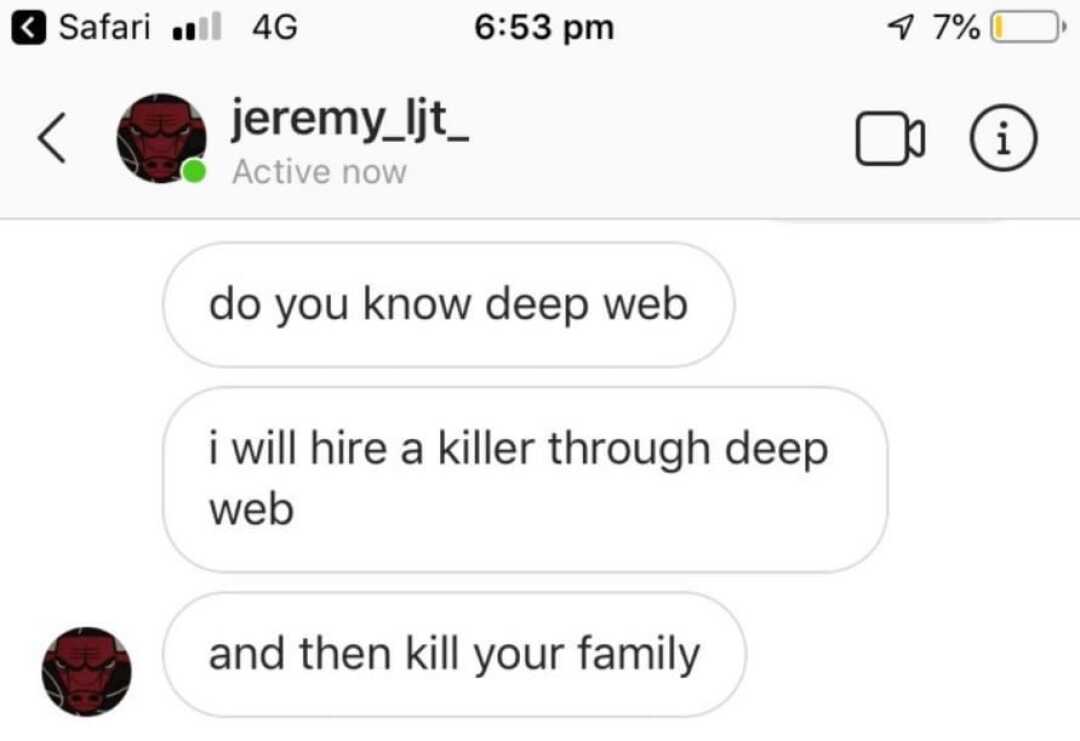

Soon after Xu’s statement, Chinese nationalists began flooding Pavlou’s social media accounts with bile:

One of several threats sent to Pavlou.

(Drew Pavlou)

China is not something your country can provoke.

White trash pig.

I will hire a killer through deep web and then kill your family.

Your mother will be raped till dead.

The threats alarmed his parents, a quiet couple who ran a grocery in Brisbane and avoided politics. When Pavlou called another protest the following week, they screamed at him to stop. Soon the family was barely speaking to him. His teenage brother and sister accused him of putting them all at risk.

His main target was Peter Høj, the university’s vice chancellor and its leading advocate of engagement with China. Høj had served on the governing council of the Chinese state agency that oversaw the global cultural centers known as Confucius Institutes, including one based at the University of Queensland. In 2015, the institutes named him an “outstanding individual of the year” at a ceremony in Shanghai.

The institutes — partly funded by China and offering language and other instruction from a Communist Party-approved curriculum — were recently labeled a propaganda operation by the State Department. Dozens on U.S. campuses have closed. At the University of Queensland, one Confucius-designed economics course espoused Beijing’s talking points about Uighurs, including that the “majority claimed to be connected with overseas extremist groups.”

Late last year, the university renewed its Confucius Institute agreement through 2024, although it added a provision strengthening its control over the curriculum. The deal proved lucrative for Høj, who earned a $148,000 bonus for meeting his performance goals, one of which was deepening ties with China.

Peter Høj, left, then vice chancellor of the University of Queensland, shakes hands with Xu Jie, the Chinese consul general in Brisbane, in 2017.

(Chinese Consulate-General, Brisbane)

Pavlou tweeted that Høj was “deeply compromised” by the relationship: “This is why he doesn’t care that students on his campus are bashed by masked CCP thugs.”

Høj, who retired in June, declined to be interviewed. A Queensland state anti-corruption commission this year found no evidence he’d acted improperly.

Pavlou fashioned himself a leftist provocateur, pushing his cause with memes and stunts one moment, passionately condemning genocide the next. Last October, he ran for a student seat on the university senate, where Høj was a member. He pledged to devote the $37,000 salary to human rights organizations — and won.

His new position didn’t stop him from unsparingly trolling anyone who wasn’t in lockstep with his opposition to the Communist Party. In one Facebook post, he held a flame to a book of Xi Jinping’s speeches outside the Chinese consulate in Sydney. Planning to start Chinese language classes, he joked about “giving Confucius Institute instructor mental breakdown.”

Administrators watched with growing dismay.

::

On April 9, Pavlou opened his email to find a 186-page document from the university titled “Disciplinary Matters.” It contained 11 allegations of misconduct ranging from the serious — harassing and bullying students and staff, damaging the university’s reputation — to the frivolous, such as using a pen at a campus store without paying.

That night, facing possible expulsion, he drove to a parking lot and cried in his car.

The dossier was a detailed chronicle of Pavlou’s social media behavior. Some of it was ugly. Weeks into the COVID-19 pandemic, he had donned an orange hazmat suit outside the Confucius Institute and said he was locking it down “UNTIL BIOHAZARD RISK CONTAINED” — a “prank” he later regretted.

Friends defended Pavlou, especially students from Hong Kong, even though they feared doing so because of reprisals from the Chinese government.

“Drew’s sometimes impulsive and irrational, like he hasn’t really thought of the consequences before acting or saying stuff,” said Jack Yiu, a 23-year-old postgraduate student. “But his beliefs are in the right place.”

Pavlou acknowledged making the statements but argued the university was punishing him for his activism. The anxiety and depression that had dogged him since childhood resurfaced. He upped his medication and decided to fight back, buoyed by growing public support, pro bono lawyers and a drumbeat of revelations that raised pressure on the university.

I just felt disgust at the way these powerful, senior men were victimizing this kid.

Patrick Jory, University of Queensland professor

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute think tank revealed that a former professor who returned to China had founded a company specializing in surveillance technology. The news raised questions about whether Australian research funds had helped Beijing monitor Uighurs or other groups. The university said it “does not condone misuse of its research” but did not comment on the details of the report.

In one move aimed at quieting critics, university officials said they would stop appointing foreign officials to honorary positions. But they allowed Xu, the Chinese diplomat, to keep his unpaid professorship until it expires in 2021. (This year, a Brisbane magistrate dismissed a case Pavlou filed against Xu for inciting violence, ruling that he was protected by diplomatic immunity.)

“Drew’s methods may have been provocative, but he’s courageous, and he has brought important scrutiny to a number of issues,” said Pearson, of Human Rights Watch. “Instead of directing its energies into throwing him out, the university should have focused on addressing Chinese government interference on its campus.”

Administrators enlisted a top-tier law firm, Minter Ellison, to serve as prosecutor in Pavlou’s disciplinary proceedings. Another firm it hired, Clayton Utz, threatened Pavlou with a contempt of court case for attempting to use in his defense documents subpoenaed in a separate legal matter.

“Hiring two international law firms, compiling this dossier — it was appalling how they could do that to a 20-year-old student who had mental health issues,” said Patrick Jory, a history lecturer who taught Pavlou. “I just felt disgust at the way these powerful, senior men were victimizing this kid.”

On May 29, the disciplinary panel handed Pavlou a two-year suspension. The verdict surprised even the university chancellor, Peter Varghese, a former Australian diplomat, who expressed concern at “the severity of the penalty.”

Six weeks later, an appeals committee threw out several of the most serious allegations and reduced Pavlou’s suspension to one semester.

Pavlou did not celebrate. The weight of the penalty, one year shy of completing his degree, broke his bravado.

“All these people sign a petition, all these politicians speak up,” he said in a Facebook video, holding back tears. “But just — nothing changes.”

::

If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy.

A Chinese official

Things were changing, however. While Pavlou served his suspension, the Chinese government accelerated a trade and diplomatic war that has underlined the risks of yoking Australia’s economy to an authoritarian system.

Unlike their counterparts in academia, Australian political leaders often pushed back against Beijing. Australia was the first country to ban the Chinese tech giant Huawei from its 5G networks and has criticized Beijing’s policies in the South China Sea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Xinjiang. After intelligence agencies found that pro-Beijing donors were funneling funds to Australian politicians, the government passed legislation to prevent espionage and foreign interference.

The last straw for China appeared to come in April, when Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s government led calls for an independent inquiry into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. One Communist Party propagandist said Australia needed to be put in its place — like scraping the gum off the bottom of a shoe.

Beijing has since blocked billions of dollars in Australian wine, barley and other exports, refused calls from Australian ministers, expelled Australian journalists and issued travel warnings to Australia for students and tourists.

China has raised import taxes on Australian wine, escalating a trade war following Canberra’s call for a probe into the origin of the coronavirus.

(Mark Schiefelbein / Associated Press)

“If you make China the enemy,” a Chinese official warned Australian news media, “China will be the enemy.”

“It’s hard to know whether we’ve reached the bottom, because when it feels like we have, then a few more trap doors open and everyone jumps into them,” said Richard McGregor, a senior fellow at the independent Lowy Institute.

The spat has shattered the idea that Australia could balance its economic partnership with China and its alliance with the U.S. — and signaled to Beijing’s other trading partners that political disagreements will carry a cost.

“China doesn’t want you to have it both ways,” McGregor said.

Although prominent business leaders continue to argue that the trade relationship must be rescued, public opinion is moving in the other direction. A Lowy Institute poll this year found that only 23% of Australians trusted China, down from 52% in 2018, and nine in 10 wanted the government to find alternative markets for its goods.

In the roiling national debate, Pavlou now occupies a prominent place — and Beijing has noticed. In August, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian accused the 21-year-old by name of “pursuing an anti-China agenda out of political motivations.”

“Last year, when I was advocating for boycotting Chinese goods, divestment and sanctions, a lot of people called me crazy and radical,” Pavlou said. “Now you see even some foreign policy experts preaching this strategy.”

He spent the 14-week suspension hunkered down at home, having patched things up with his family. Working out of his bedroom — where the walls are plastered with the flags of East Turkestan, a symbol of Uighur independence, and Mexican Zapatista rebels — he kept busy tutoring high school students, setting up a human rights group called Defend Democracy and preparing for state Supreme Court hearings in a $2.6-million defamation lawsuit he filed against the university.

At midnight Nov. 23, when the suspension expired, he and some friends lit cigars at the campus entrance and popped bottles of bubbly. Someone yelled, “He’s back!” In February, when the new semester begins, Australia’s most notorious undergraduate will return. He may not be alone in hoping it will be his final year of classes.

Special correspondent Petrakis reported from Melbourne and Times staff writer Bengali from Singapore.

This is the seventh in a series of occasional articles about the effect China’s global power is having on nations and people’s lives.

More ‘In China’s Shadow’ series