Only later did I realise that the early years of William Wordsworth’s life, as he distilled them in his epic autobiographical poem The Prelude, had come alive again and again in my childhood Lakeland experience of adventure, excitement and tranquillity.

Mountains playing hide and seek in the clouds, sometimes hiding all day. Lakes to swim in; lambs leaping or sheep meandering; water rushing or pooling, sparkling like diamonds or mysteriously brown with peat, masking the fish. Walking in the fells I was free to join the streams without adult restraint and get soaked to the skin; infinity to climb and explore and wonders to stop still and gaze at.

I saw that the variety of cloud and light, the vagaries of wind, transform views with the twist of a kaleidoscope while the sky illumines, gentles, highlights or obscures. A shaft of sunlight through mist can seem miraculous, the subtle variety of colours, magnified in intensity by the light, joyful. I discovered the Langdale Pikes, which became – and remain – my household gods. Home to the great English neolithic stone axe factory, their particular spirit has been reverenced for 6,000 years – since the time when a polished pike axe-head was laid in the circular ditch at Stonehenge, pre-dating the arrival of its famous stones.

At the other end of my life, once my husband and I retired, I had a strong yen to return. Hardly debated, this happened in a flash as, while staying near Keswick, we heard that the old Crosthwaite Vicarage was for sale, the house where Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, indefatigable “Defender of the Lakes” and one of the three people who started the National Trust, had lived for 34 years. We knocked on the door and were invited into its drawing room, where light flooded through large Georgian windows, framing an inexpressibly magnificent view of range after range of north-western fells. On the terrace, we saw the slate where Rawnsley had carved the poet Thomas Gray’s description of the view as “the sweetest scene I can yet discover in point of pastoral beauty”.

We were both caught and soon started to dig into the history of our new home, once at the heart of the old 90 square mile Crosthwaite parish, its boundary travelling the tops of a magic circle of mountains: Skiddaw, Helvellyn and Great Gable. We found that the church, Saint Kentigern’s, was the oldest parish church in the area, the only one for some 200 years. It sits low on its land, like the Lakeland stone farmhouses of the 17th century, and is buttressed and battlemented like the medieval pele towers of Cumberland; for Robert Southey its tower rises “upward fixedly/Like stedfast hope beneath some careless wrong”. Inside there is an exceptional sense of light and space, remains of the Norman architecture, some medieval stained glass, the tombs of the Derwentwaters who once owned the land, a huge wooden bar to the main door to keep out Scottish reivers and a rare northern late-14th-century font.

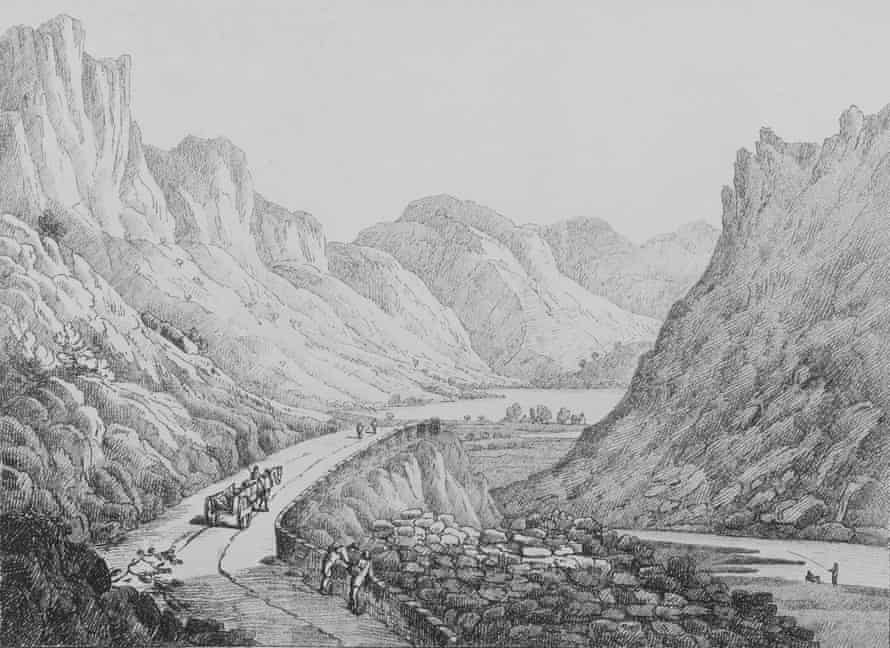

You can enter the old parish from Ambleside and Grasmere over the pass of Dunmail Raise, with a cairn on the central reservation at its top – “… that pile of stones/Heaped over brave King Dunmail’s bones”, as Wordsworth wrote in his poem The Waggoner. The cairn was believed for centuries to commemorate the warrior’s death in the late 10th century during the last great battle with England’s King Edmund I. In fact, Dunmail survived the battle yet by tradition each year his old warriors still return to the great cairn for further instructions. Upon descending the Raise you come to the Kings Head Inn, Thirlmere, visited by many famous literary travellers, including Wordsworth.

Thirlmere is now accessible again, after more than 100 years’ closure once it became Manchester’s reservoir. And just before Keswick a short detour will allow you to stand at the centre of the prehistoric Castlerigg stone circle, offering as great a 360-degree prospect of the Lake District as you can find.

Keswick became the first market town of the Lake District, in 1296, and long remained so. Today’s markets on Thursday and Saturday are still a big draw, as is its Moot Hall, once owned by the Derwentwaters and long the home of their manor courts. Five large, and fine, 19th-century stained-glass windows grace what was the Poets Dining Room of the old Royal Oak Hotel (now a shop called Poets Interiors in the alleyway between Packhorse Court and Station Road). Three are now obscured (complain!) but Samuel Taylor Coleridge and celebrated huntsman John Peel (D’ye ken?) remain. Peel’s Blencathra pack would meet in the market square and at the Pheasant Inn on Crosthwaite Road.

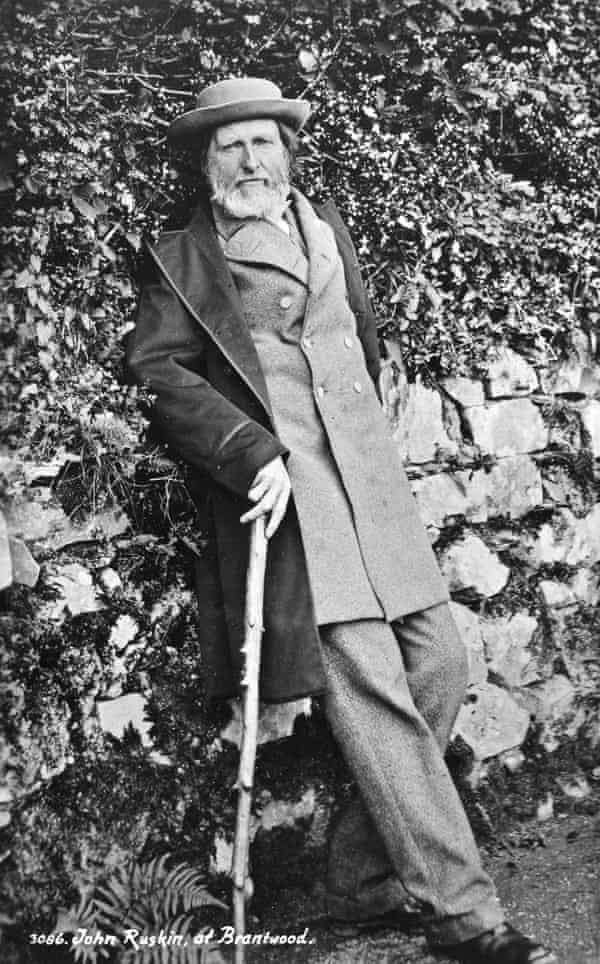

A stroll past the excellent Theatre by the Lake and along the east side of Derwentwater brings you to Friar’s Crag and the view John Ruskin considered seminal in the creation of his own taste. Here a fine monolith of Borrowdale slate, with Ruskin’s portrait in bronze relief, commemorates him. Organised by Rawnsley for the National Trust, it lies on land later to be purchased for the Trust in Rawnsley’s honour.

Rawnsley introduced more interest into Saint Kentigern’s after George Gilbert Scott’s 1845 re-ordering of the Tudor church had left a largely empty interior. This includes a new baptistry, dedicated to the Rawnsleys, but pride of place, for me, goes to the large reredos and altar resetting. The mosaic floor was done by a specialist but, gloriously for the parish, the three large bronze panels were worked entirely by students of the Keswick School of Industrial Arts, which Rawnsley and his wife Edith started in 1884 to help with winter unemployment. Crossing the bridge from Keswick towards Saint Kentigerns, you can see the school’s old home, displaying the 1894 couplet: “The loving eye and skilful hand / Shall work with joy and bless the land.” The school lasted 100 years; its work, praised at the time by artists including Holman Hunt, is still collected today.

The great ridge walk called the Newlands Horseshoe is a classic, but Cat Bells, towards its end, is probably the most popular tourist mountain. It will be crowded, but continue south to Maiden Moor and you will experience a different magisterial view of more mountains. You can also approach Maiden Moor by branching out at the mine workings from a circular low-level walk (starting at Skelgill) largely on old shepherd and corpse roads, around the edge of Newlands valley. Here there are far more sheep than people and some delicious cakes or sandwiches await you halfway around at Littletown Farm, the inspiration for Beatrix Potter’s Tale of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle.

This is a favourite walk for us and, having begun to explore the social history of the parish, we knew that we were walking upon paths trodden since the early middle ages and, in parts, by the Vikings. The lower return path was used by medieval milkmaids taking cows to and from an old Viking pasture just above Littletown to Portinscale for milking. That this daily task – four miles each way – underlines the lack of good pasture then and is evidence that the landscape we love is the living heritage of ages of sheep farming. Heralded by Wordsworth as a divine symbiosis of beauty and use, shepherding is at the heart of the “outstanding universal value of a cultural landscape: for which the Lake District achieved Unesco world heritage status in 2017. A fine memorial, made from a “clog” of Honister slate and unveiled by the Prince of Wales, celebrates this on the shores of Derwentwater at Crow Park.

In the 13th century, land in Keswick valley was acquired by two great Cistercian abbeys, Fountains and Furness, whose monks first developed sheep-keeping into a trade in England, and greatly enhanced the hill farmer’s skills. The Furness monks had their local headquarters at the village of Grange at the southern end of Derwentwater, and the patterns of the fields in the Borrowdale valley still reflect their management, as does the course of the River Derwent: some believe the monks’ changes add to today’s difficulties in managing flood water. After the Reformation until the second half of the 19th century, education, poor relief and management of the commons and the roads were overseen by tenants called the Eighteen Sworn Men.

The masterpiece of the 90 square miles of the old Crosthwaite Parish could never have been achieved without the hundreds of years of their ordering of the land, without Wordsworth and Southey, without Rawnsley’s saving of land and landscape for the people, and without the toil and care of its shepherds, from the Vikings until today. Enjoy.