The setting sun is bathing the River Dart in gold and pink as our small flotilla of canoes journeys upstream. I reach for my phone to take a picture, then remember it is switched off and stashed in my tent, where it will remain for the next four days. I bite back a remark to Emily, with whom I am sharing a canoe, as we have been asked to paddle in silence. We are trying to find “stillness and flow”. At twilight, our hush is rewarded when we hear an owl hooting. Darkness has descended by the time we reach dry land and walk back to camp, head torches lighting the way.

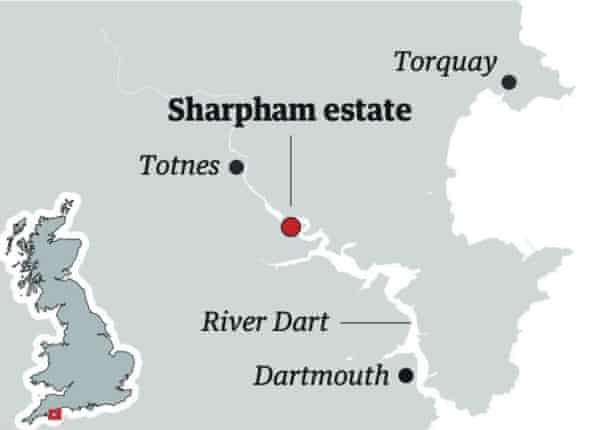

This was a recce paddle on the first night of a canoeing and mindfulness retreat at the Sharpham estate near Totnes in Devon. The 550-acre estate includes Sharpham House, an 18th-century Palladian villa, the Barn retreat centre, a woodland campsite, a natural burial ground, a farm, vineyard, dairy and restaurant. It is run by the Sharpham Trust, a charity set up in 1982 to help build “a more mindful, compassionate and environmentally sustainable world”. That means farming organically, generating renewable energy and promoting biodiversity. The trust also runs affordable retreats, mindfulness courses, art projects and events such as bat and stargazing walks, wild medicine foraging days and food fermenting workshops.

The house, barn and woodland are all retreat venues, hosting about 2,000 people a year – but demand still outstrips supply. Pre-pandemic, it was fully booked with long waiting lists. Now the trust is spending £1.6m to convert a Grade II-listed stable yard, built in 1760, into the Coach House, with 18 en suite rooms and a meditation space. From January 2022 there will be space for another 1,000 people a year on weekly mindfulness retreats.

I got a place on a woodland retreat thanks to a cancellation. After choosing my bell tent from the dozen or so dotted among the trees, I attended the opening “sharing circle” in the “fire temple”, an open-sided structure with two campfires. We introduced ourselves and explained what had brought us on retreat, from wanting to spend time in nature to feeling lonely during lockdown. The honesty was moving. We were a group of about 15 women, aged roughly 30 to sixtysomething. Most had been on a Sharpham retreat before – it is a place that draws people back.

The rhythm of our days was: 6.30am wakeup songs by Rupert Marques, our mindfulness teacher; then breakfast at seven, on the water for eight, back for lunch, free time, afternoon meditation, dinner, more meditation, circle and fire.

The first morning paddle was upstream to the edge of Totnes, in stable Canadian canoes. The instructors, Hannah, David and Nigel, explained that the person in the front of the canoe is the engine, and the one in the back steers. They gave a few basic technique tips: use your body to paddle, not just your arms; how to use the oar as a rudder; the sweep stroke for turning.

We took a tributary into water meadows and paddled slowly in silence, looking at the eddies in the stream and listening to the rhythmic plash of our oars. We meditated in a meadow backed by rolling farmland before turning for home. The serenity was shattered when we jumped in the river for a swim – it was shockingly cold, with a strong current.

The next morning we paddled downstream towards Dartmouth, stopping to “forest bathe” in a wood, and to swim in a calm, shallow spot. We paddled alongside the Sharpham seal, a regular visitor, and a pair of swans flew back and forth over our heads so low we could hear the hum of their wings.

While the canoeing was a form of moving meditation, most of the still meditation took place in the afternoons, in the Capability Brown-designed gardens, and the evenings, in a marquee. Rupert would talk, and then we would sit still for half an hour – a long time for the unpractised. I found the “aimless wanderings” easier: walking without a purpose other than paying attention to everything we saw, heard, smelled and touched. Sharpham is on a hill in a bend in the river, encircled by water on three sides, and I could have stood and watched the Dart for hours. I spent 45 minutes in the 18th-century walled garden, examining each flower and fruit.

This garden and the wider estate were the source of most of our delicious, vegetarian food. Dinner might be callaloo soup with local bread, followed by squash and pea pilaf, salad with edible flowers and homemade dips, then lemon posset. In our free time, I recreated the canoe journeys on foot, walking along high cycle paths with river views and low woodland footpaths. It felt fantastic to be outside and moving all day after months of being cooped up at home.

At the final circle, we shared how we felt, listened to Rupert’s stories and sang call-and-response songs around the fire. Had I found stillness and flow? At the very least, I’d forgotten all about my phone.