I was lying on my stomach on a clifftop waiting for a puffin to stop preening long enough for me to take its photo with my little camera. A couple of women were sitting on the grass nearby, huge lenses trained on the bird. I had one eye on the puffin but my ear on the women – “I’ve only taken 86 photos, so it shouldn’t take long to edit them.”

I put my camera down. Watching a puffin no more than a metre from me combing its beak through its feathers was a moment that would stick in my memory even without a great photo.

The uninhabited isle of Lunga rises out of the sea like a mythical land – its basalt cliffs jagged and intimidating, the air alive with wheeling sea birds. Nearly 50 species can be spotted here, including kittiwakes, guillemots, fulmars and shags – but it’s the 8,000-strong puffin colony that steals the show, returning from the sea with mouths full of sand eels and scurrying in and out of burrows, seemingly unperturbed by human visitors.

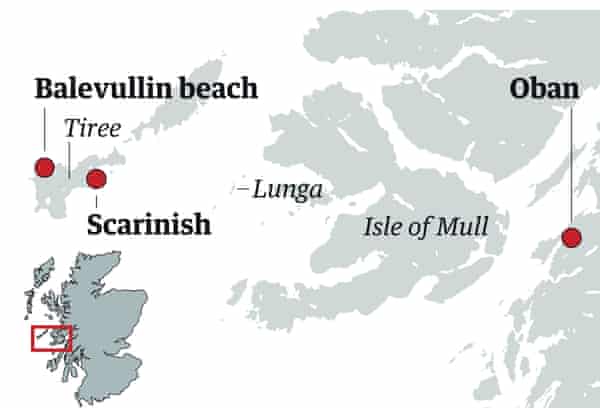

Getting to Lunga, a speck of land just west of the Isle of Mull, had been an adventure itself. At the tiny harbour in Scarinish on Tiree our group was split in two; ours was allocated to the 12-seater rib, which meant donning comically large waterproofs before boarding.

“Make sure you hold on,” Kris the captain told us. Moments later it was clear why, as the boat bounced over the waves, speeding past the other group’s catamaran. The journey there and back provided its own wildlife displays as we cruised through a pod of dolphins that leapt alongside the boat almost within touching distance. The catamaran crew even spotted a minke whale. It was only after talking to some fellow passengers that I realised how lucky we had been on Lunga. Our group of 22 had the island to ourselves. It hadn’t crossed my mind that it might be busier in a normal, non-Covid year.

“That path we walked up is usually rammed,” one of the group told me. “Hundreds of people come over from Mull on big boats.”

Perhaps we had taken the peace and quiet on Lunga for granted because we’d got used to having places to ourselves on the Isle of Tiree. The most westerly of the Inner Hebrides, Tiree is only 12 miles long and three wide but the lack of hills or trees, towns or traffic, gives a sense of space that belies its size. As we drove across the “Reef”, the name given to the centre of the island, I was reminded of the American prairies or the pampas. The land is pancake-flat and dwarfed by a sky so vast it feels like it might swallow the island whole.

“It’s a very powerful landscape,” said John Holliday, a retired GP who has lived on the island for 30 years and is chair of the local museum. “But it’s almost impossible to capture. Several photographers have moved here, but it’s incredibly difficult to frame any picture, to curate a composition.”

It’s odd that the big skies are not referenced in the various monikers by which Tiree is known. It’s the Sunshine Isle, on account of its reputation as the sunniest place in Britain (not strictly true); and the Hawaii of the North, thanks to its great surf. With white-sand beaches all around its 36-mile coast, you are almost guaranteed great surf conditions. As well as board-surfing, Tiree is renowned for kitesurfing and windsurfing, hosting the longest-running pro windsurfing event in the world every October.

“The surf’s really good at Balevullin today,” Sian Milne, owner of the Reef Inn, the island’s first boutique hotel, said to us when we arrived. Opened this spring, a year later than planned, it didn’t have an ideal start, but the eight bedrooms are almost fully booked this summer. Inside, black furnishings and plants stand out against white walls and pale wood floors, its minimalist Nordic design a departure from the island’s two more traditional hotels, the Lodge and the Scarinish, although the latter is about to reopen after a revamp.

But if the Reef is cool and luxurious in its design, the vibe is warm and laid-back. Sian’s friendly “surf’s up” welcome set the tone for our stay: I ended up going for an early morning dip with Michelle, the waitress, after discovering she loved outdoor swimming; my son kept popping over to Sian’s garden, next to the hotel, to hang out with her four children.

Half an hour after we’d checked in we were standing above Balevullin beach grinning at the wide curve of white sand backed by marram grass dunes, with barely a soul on it.

Balevullin is home to Blackhouse Watersports, a surf school run by Iona and Marti Larg. We joined a group lesson and spent the next 90 minutes managing to get up on to our hands and knees, with a few brief, wobbly standups. I walked back up the beach with a sense of, if not achievement, satisfaction that I’d given it a go.

Over the next few days we returned to Balevullin to surf with Iona, watching in awe as their 16-year-old son, Ben, a competitive surfer, paddled out to catch the bigger swell. Between surf lessons we tried windsurfing on Loch Bhasapol with Wild Diamond (even harder than surfing). When we weren’t falling off boards into the water, we walked along the coast, poked about in rock pools, and even managed a swim without wetsuits one day.

Every beach we visited was ludicrously picturesque, from the dazzling Green, a short walk from the island’s only high school, to the little roadside coves just outside Scarinish. But 4km-long Gott bay is particularly mesmerising, its vast shimmering sands reflecting the sky at low tide. At its eastern end is a cluster of cottages – the traditional blackhouses that the surf school takes its name from, so called because originally these deep-walled, thatched buildings had no chimneys and their insides would blacken with smoke. Only a handful are still thatched; most roofs have been replaced with tarred felt.

Like its landscape, Tiree’s history is one of extremes. The island’s shallow fertile sea is rich in kelp. In the late 1700s the Duke of Argyll began to make money from this “brown gold”, which was harvested and shipped to the mainland for use by soap and glass manufacturers and for linen bleaching. The population increased threefold in 50 years, but when the price of kelp fell and the harvest failed, famine and poverty led to mass emigration.

“It’s a very extreme story: a massive increase in population, unmatched anywhere else in Scotland, then a plunge into poverty, then huge emigration. It had a profound effect,” said Holliday. Today 650 people live on the island, but the population is slowly starting to increase, creating, said Holliday, “an interesting new story for the island”.

“The signs are encouraging: there are families moving to the island. People are starting to leave the cities because they can work remotely, and taking advantage of [the better] quality of life.”

People are also starting to holiday on the island more. Unable to travel abroad, fair-weather surfers, windsurfers and kite surfers who might have headed to Portugal or Tarifa in southern Spain are braving the chillier waters of Tiree. But it’s not just watersports enthusiasts who are drawn to the island. Overcrowding in Cornwall, Devon and the Lakes is encouraging UK holidaymakers to seek out more remote places where they can picnic on a beach in relative peace.

Tiree Sea tours, the company that took us to Lunga, was set up in 2018 by former fisherman Frazer MacInnes. Business is booming and he plans to buy a second rib this year. “The island is getting a good name for wildlife tourism. I made more money this May than in the whole of last year,” he said.

In the far south-west of the island, a former builder’s shed houses another entrepreneurial venture, the island’s first distillery in more than 200 years. Set up in 2019 by friends and folk musicians Ian Smith and Alain Campbell, the distillery produces Tyree Gin, using botanicals from the machair, the fertile grazing ground that is covered in wildflowers in summer.

This spring the pair opened a small terrace overlooking the rocks on the south coast serving gin cocktails (try the Tyree raspberry sour). The first batch of whisky will be ready in three years.

In the evenings we ate at the Reef Inn’s restaurant; huge photos of waves and surfers decorate the walls and floor-to-ceiling windows provide light. Standout starters were mussels with pancetta and cider, and a chowder that was almost a meal in itself. I had an excellent potato-and-cauliflower curry; and some great langoustines.

Until the Scarinish Hotel reopens later this month, the only other place for an evening meal is the Lodge Hotel. We grabbed takeaway fish and chips from there one evening and ate them sitting by the harbour. There was no one else around – just some sheep nibbling at the grassy verges.

“The outside world has tended not to fix their gaze here,” Holliday told me. But with the ongoing international travel restrictions and the blossoming of new businesses like the Reef Hotel, the outside world is starting to notice the “secret island” of Tiree.