I first learned about fly-fishing in a story by Truman Capote called Handcarved Coffins. In America’s midwest, Capote’s help is solicited by a small-town sheriff stumped by a string of diabolically ingenious murders in his remote farming community. The victims have been are killed in ways suggesting intimate knowledge of their habits, yet nowhere is there any apparent motive. In the end Capote has no evidence but meets up with the man he reasons must be the killer. He’s fly-fishing. Waist-high in a stream, he talks about the “will of God”. As little as I then knew about the sport, it somehow made perfect sense that the killer would be fly-fishing.

In a larger sense, fly-fishing is a discipline of the mind, about things unseen. In the run-up to my trip to Sweden’s fly-fishing mecca Älvdalen, four hours north of Stockholm, I listened to fly-fishing stories on the internet. Many are about technique, or about making the “flies,” and the tiny lures fly-fishers use; also, oddly, there are a great many tales about fly-fishing as a sort of personal, even spiritual, quest, about people who go to restore a relationship, to help them unravel some knotty issue in their lives or just find peace of mind. Somehow fly-fishing makes that possible.

-

Clockwise from top: Giulio Marchesi, from Milan, fishing on the Österdalälven River in Älvdalen. In the fly-fisher’s armoury are an assortment of flies that attempt to match the natural insect hatch, including the superpuppa, which imitates a Mayfly

Micke Nyberg, a local guide who runs an outfit called Anglerman Fishing Adventures, picked me up at the Älvdalen Fishing Center. Micke is a big bear of a man. His family has lived in the area since the 16th century. He is fluent in several languages, including Avdelska, a local language that’s a mix of old-English, old-German, old-Swedish and old-Icelandic, and utterly unintelligible to all but a few. He likes it that way. With him is Giulio Marchesi, an architect from Milan who comes to fly-fish with Micke every year.

At Micke’s shop, we’re fitted out with boots and waders and head out on to the highway, turning off on to a dirt track that is soon swallowed by dark forest. I notice there’s nothing on the GPS. We’re quite literally off the map. If you could find this place, it would be all too easy, and no fun at all, to get lost here. We emerge beside a small river. This area is crisscrossed by rivers. Micke and Giulio stand in silence on the bank and watch. They’re looking for fish rising to grab one of the mayflies that flit about on the surface.

The next morning we head out, not too early, for a different spot. It’s a perfect day. Micke escorts me across the stream to a small island. I’m very nervous about slipping on slick rocks which would spell death to my cameras, but Micke is big, stable and has “sea legs”, and as we go he’s instructing me how to walk without falling.

“When I was young,” he says, “it was about catching fish. Then it was about catching many fish. Then it was about catching bigger fish. Now I get satisfaction out of enabling other people to catch fish.” Micke and Giulio try the spot for a while but it yields nothing, so we pile into the truck and head to another stretch of the river. It’s like this all day.

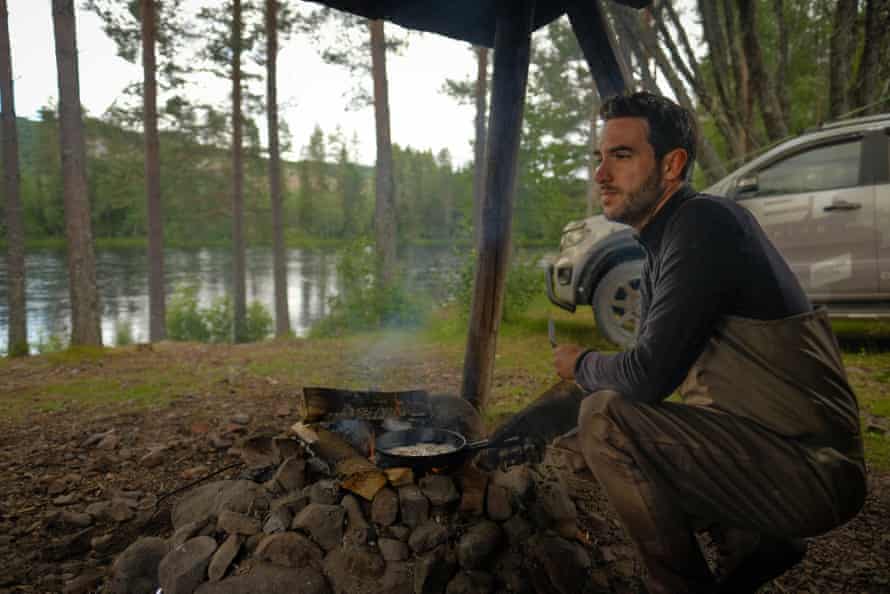

We stop for lunch at a small shelter alongside a stream. Micke builds a fire, produces a cast-iron pan and begins to make a local favourite called kolbulla. It’s an absolutely outstanding pork pancake made with a savoury batter served in the traditional way with lingonberry jam. Asked for the recipe, Micke just laughs. The meal is finished off with some strong Swedish coffee and a bit of dark chocolate. Totally satisfying.

![Alvdalen, Sweden: “Once you start [flyfishing],” says Giulio,” you never stop.”](https://dailyamerica.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/1629957875_354_Zen-and-the-art-of-fly-fishing-in-Sweden-–-a.jpg)

“Fly-fishing,” says Giulio, “is all about focus.”

“You’re doing only one thing. You’re here and nowhere else,” adds Micke.

The angler is acutely attuned to every sight, sound and smell. The stream is still or moving. Fish can sense your presence. A fast current generates sound that can hide you. Insects are flitting about on the surface. Small birds are zooming about chasing the insects. What kind of insects are they? Where are they? Brown trout and grayling, the fish that live here, eat mayflies and other hatching insects. You watch the surface for bubbles and patterns that might betray a fish. With the flick of the wrist, an experienced angler can cast his or her line to the exact spot where a fish is feeding.

The moving current can induce a kind of spatial disorientation, so you have to concentrate. If you’re using the right fly, and it lands within the small radius where the fish will strike, and if the fish lunges for it maybe you’ve got one. But usually you haven’t and you try again.

-

Guide Micke Nyborg’s family have lived in the Älvdalen area for 500 years, and he is a lifelong angler. After a blank spell, he changes his fly to one that is microscopically larger and instantly nets a trout

“The intense focus fills your senses. The coolness of the water, the gentle buffeting by the current, the sound of water moving over rock and gurgling up from the hollows, the feel and smell of spray rising from the stream mixing with the smell of pine trees … you emerge from it like you’ve had the best-ever mindfulness meditation. Your mind is clear and feels like it has never worked better,” says Giulio.

He adds: “It gives energy back. I really need to do it. Back home, I sometimes just go fishing because I want to do it. I want to do something else for half a day but I don’t get the same amount of good energy and positive thinking that I get from being here. Once you start fly-fishing you never stop.”

For details visit Anglerman Fishing Adventures . Further information at visitsweden.com