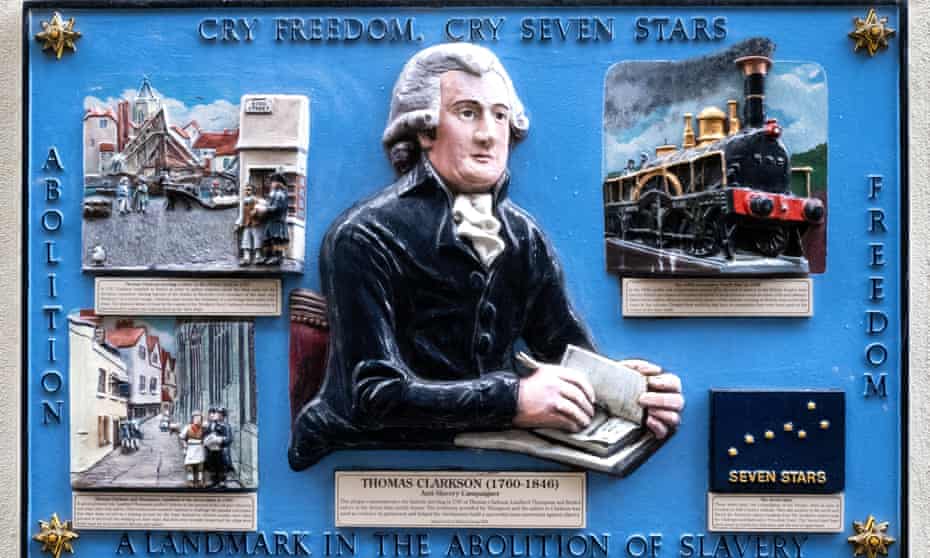

“Important bit of history that,” a warm West Country voice says over my shoulder as we look at the plaque outside the Seven Stars pub, a 17th-century landmark of the abolition movement.

If you block out the posters for the band “Kunts” adorned with a large image of Boris Johnson, and instead focus on the cobbled streets and Georgian walls, you can imagine the secret meetings between abolitionists and slave ship sailors.

This particular plaque commemorates Thomas Clarkson, an anti-slavery activist who, with the help of Seven Stars landlord Thompson (his full name is not known), collected testimonies from sailors in 1787. Used as evidence in parliament, the testimonies helped to achieve the passing of the 1807 Slave Trade Act and eventually led to the end of the British slave trade.

Blue badge tour guide Rob Collin takes me around Bristol, guiding me through the city I grew up in, but whose history I was never taught. Last summer, protesters in the city toppled a statue of slave trader Edward Colston. Collin’s care and passion for representing the warts-and-all truth of Bristol’s involvement in the slave trade is unfaltering, even as our hands freeze around our umbrella handles in the rain.

“If all you’re going to portray to the outside world is that which is good … you’re rewriting history to your own agenda. That’s dangerous. The whole purpose of a walk like this is to try to understand the past, so we can understand the present,” he says.

As we stand at Colston’s plinth, on Colston Street, next to what was (until last year) Colston Hall and Colston Tower, we learn about the man. In 1680 he became a board member and then deputy governor of the Royal African Company (RAC), the most prolific slave-trading company in British history. During his time there (his involvement ended in 1692), it shipped an estimated 84,000 people from the coast of Africa to plantations in the new world. About 19,000 of them didn’t even complete the treacherous journey: they spent their last days chained to the ship’s decks before their bodies were thrown into the sea.

There aren’t many records of how much money Colston made from trading enslaved people, but there is plenty of information about his philanthropy afterwards. More than 100 years after his death, as Bristol’s harbour closed for commercial use, Colston was held up as a hero, and his slave-trading past was sanitised and ignored.

We head next to the Drawbridge pub, right in the centre, where the harbour was carved into the middle of the city. Now, it’s an elongated roundabout where traffic lights, locals and historical relics interlace with a recent fleet of pink e-scooters. A replica of the figurehead from the Demerara steamship stands above this pub as a reminder of Bristol’s long history importing sugar. The colourful statue wearing a red sash is meant to depict an indigenous chief, a spear in his left hand, and some greenery in his right representing the “bounty of the West Indies”.

In the 18th century, sugar quickly became Bristol’s most lucrative import and the city was a booming hub of the triangular trade. Arms, textiles and wine were shipped from Europe to Africa in return for enslaved people, who were shipped to the Americas to work on plantations to grow sugar, tobacco, cocoa and coffee, which were then shipped back to Europe.

Collin describes how the tentacles of the trade sprawled into all cities, through the snuff in Briton’s noses to the sugar in their tea, and how money made from slavery funded many of the UK’s universities, banks, bridges, schools and buildings.

“When trade and commerce dominate, the moral imperative will always be set aside,” says Collin. He dismisses the claim that everyone agreed with slavery during the height of its practice in Britain. Instead he says, “We understood the abhorrence of the slave trade, but because of the economic argument for slavery, we became indifferent to the abuse of Africans in the slave trade.”

In Bristol, money from the trade went into Clifton suspension bridge, Bristol Cathedral’s stained glass windows, and Bristol University’s main Wills Memorial Building, to name a few.

Standing in front of the cathedral, Collin begins explaining the slave trade remnants found inside. The most prominent window, beneath a gold clock in the north transept, is dedicated to Colston and features a tall dome of intricate cobalt, red and turquoise panels, with the initials EC picked out underneath the images of Jesus and the centurion. Also in the transept are stone memorial tablets of former plantation orders in the West Indies, including Abraham Cumberbatch (a direct relation of actor Benedict) who owned a sugar plantation in Barbados.

Outside as we look up Park street, the University of Bristol’s Wills Memorial Building towers over the city at the top of the hill. Students have protested to get the name of the building changed because they believe it celebrates the Wills family of tobacco magnates whose wealth also stemmed from slavery. But given that most of the funding for the university came from the Wills family, the university decided to keep the name.

Collin’s slave trade tour runs year-round, but he’s getting more interest now it’s Black History Month. Understanding the impact the past has on our present and future is vital, he says. “The absence of knowledge leaves people in polarised positions. But if history is used as a positive force, you develop empathy for other people, which can only impact our relationships positively.”

Bristol Slave Trade Walk £10 adult/£5 child, Sundays 12pm-3pm

More Black History Month events

In Glasgow, there’s a slave trade tour (free, every Sunday to 30 October) with the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights, and Edinburgh is hosting a Talking Statues tour, which explores the city’s statues and their history.

Manchester has its own slave trade walk (free, 17 October) led by historian Ed Glinert, as well as a specially curated programme at HOME arts space.

At Sheffield’s Theatre Deli, Lekhani Chirwa is staging her “bold yet humorous” theatre piece Can I Touch Your Hair (from £13, 14 October) about acceptance of identity and microaggressions.

In London there’s a black history river cruise (£36, 2pm-5pm, 23 October) along the Thames with guest speakers who give a history of slavery in London and what they call “the real pirates of the Caribbean”.