The Mountain Bothies Association (MBA) charity has reopened its 105 mountain huts, shelters and howffs after more than a year of closure due to Covid. The overwhelming majority of these are in Scotland and they reopened in August for what the MBA described as “responsible use”, pointing out that Covid has not gone away. The bothies are all sorts of shapes and sizes in varied locations – many are extremely remote and operated with the agreement of owners and estates and maintained by MBA volunteers since the late 60s and early 70s.

-

Above,Allt nam Fang, approaching Meanach Bothy; right, Meanach Bothy, renovated in 1977, is approximately 1,000ft above sea level

The word bothy comes from the Gaelic “bothan” for small dwelling, hut, hovel or shebeen. The bothies are not purpose-built, so their locations and nature are fairly random. They are often not near established routes nor near popular locations. Many were built to house shepherds and estate workers during the 19th century following a period where the rural population faced eviction, clearance and emigration. Many highland estates turned their backs on the people and turned their land over to stag shooting and sheep rearing.

The passion for summer dwellings on moors and mountains in Scotland long pre-dates the Highland clearances in the 18th and 19th centuries, going back hundreds of years. Ruins of small stone airighean (roughly constructed hut used while pasturing animals) speckle the landscape in many north-western highland and island areas, and the memory of this culture lives on in a wealth of Gaelic songs and stories. These are tales of courtships, broken hearts, shape-shifting water horses and many other mysterious happenings.

There are a few shelters that are not part of the MBA network. After the second world war, there was an increased interest in men and women exploring the hills and mountains of Scotland – as celebrated and inspired by the likes of adventurers Nan Shepherd, Bill Murray, Hamish MacInnes, Tom Patey and many others.

The Secret Howff

Skiers, climbers and mountaineers have always sought refuge and shelter in the hills for weekends and overnight stays. Many estates discouraged camping and did not allow huts to be built. So a cat-and-mouse game developed, with climbers building huts or howffs in secret, some being dismantled or set on fire by estates. The ones that evaded discovery provided refuge to many during the 50s and 60s. The virtual sole survivor is the Secret Howff. Built in 1952 by four friends from Aberdeen, it was thoroughly refurbished in 2017 with, in a sign of the changed times, the assistance of the now-supportive estate. Very nice it is too. “Where is it?” you ask. “Can’t tell you, it’s a secret,” is the inevitable response. It took me a while and some small detective work to find it, accompanied by civil servant Graeme Marshall – a keen boulderer and climber.

-

Above, Graeme Marshall practises his bouldering skills en route to Leabaidh an Daimh Bhuidhe at the Sneck by Ben Avon in the Cairngorms; below, Graeme heading for the summit of Ben Avon

Graeme says: “Bothy culture embodies the lifestyle of many outdoor enthusiasts. It has always been a place where I have been able to relax, laugh and share experiences. The mountain bothy truly is a place of sanctuary.” The howff continues to be maintained by a small dedicated team of enthusiasts and remains open to day trippers and for overnight stays. Constructed from shattered quartzite it sleeps two comfortably, under the watchful eye of a carved osprey and an old ice-cream advertisement. It has a folder containing the History of The Secret Howff, and a visitors book kept in an ammunition box. So, as they say, when you find the secret, keep it.

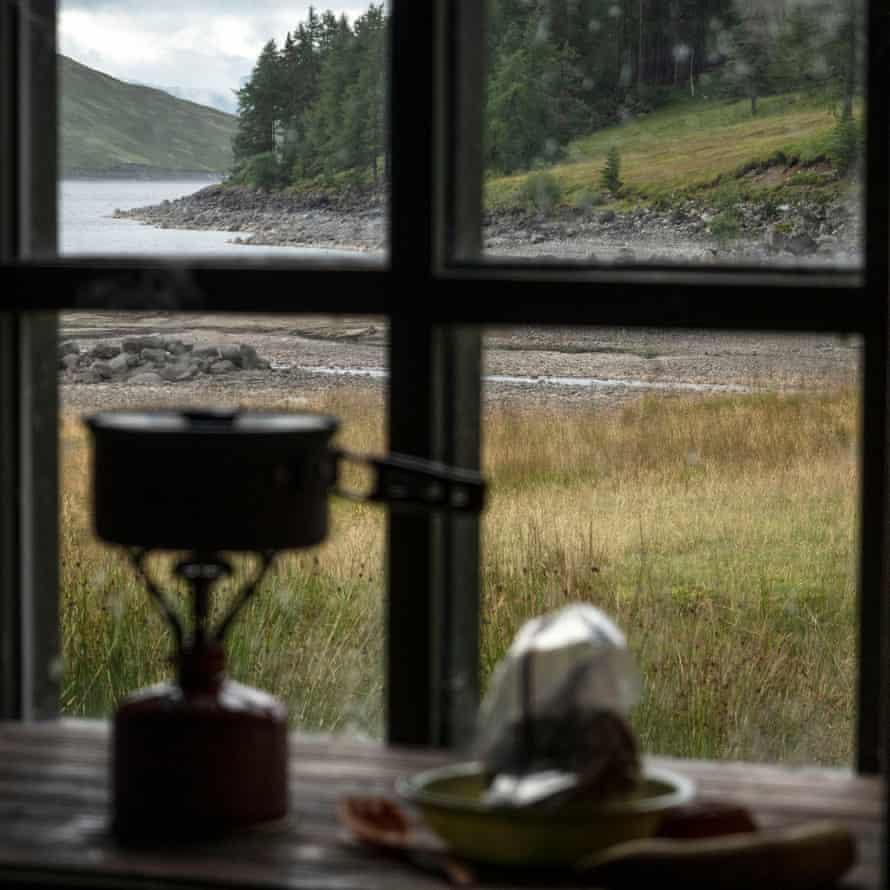

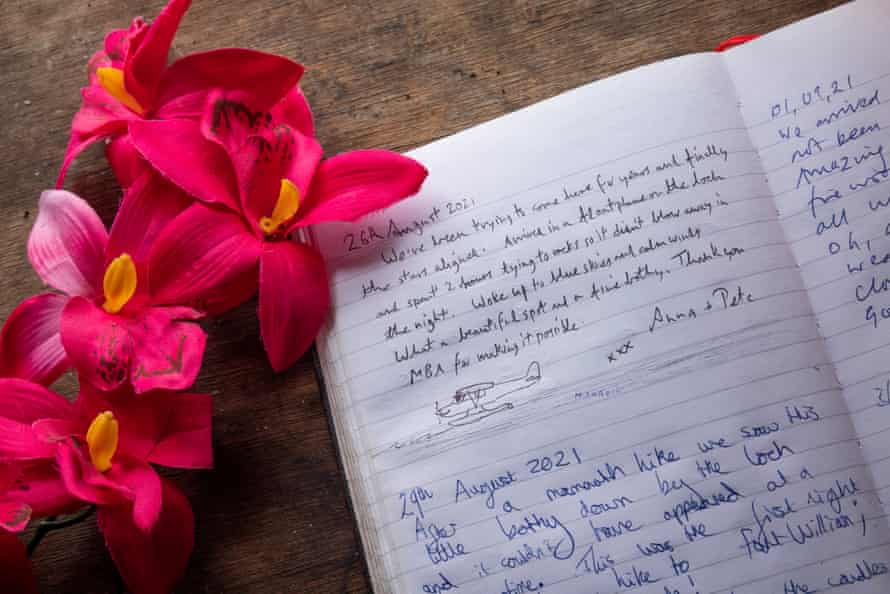

Ben Alder Cottage, Loch Ericht

Dating back to 1871, Ben Alder Cottage is a former home to estate workers and navvies. In the 20th century a false story was circulated, claiming a deer stalker had hung himself there, in an attempt to discourage poachers and tramps from staying.

-

Above, Ben Alder Cottage beside Loch Ericht; right: an animal skull hangs from the ceiling, looking out on Loch Ericht, and the visitors’ book

Subsequent tales of supernatural disturbances found their way into contemporary print and hence a legend was born. Many still get spooked. I cycled in from Dalwhinnie by Loch Ericht and Loch Pattack to the closed Culra Bothy (unlocked for emergencies, but clearly marked as closed due to asbestos having been found in the roof). From there, I continued to Sron Bealach Beithe and Loch a’ Bhealach Bheithe to the summit of Ben Alder, then down to Ben Alder Cottage by the shore of Loch Ericht.

The Shelter Stone, Loch Avon (aka Loch A’an)

It is a dramatic decent down Coire Raibeirt to the sandy beaches of Loch Avon in the Cairngorms. There, in a broken boulder field, is an enormous rock known as the Shelter Stone. If you crawl beneath it, you’ll find yourself in a small cavern. Sleeping four – kind of comfortably – it too has a long history and its own visitors’ book in a sealed container.

In Nan Shepherd’s book The Living Mountain, she gives an account of two young boys, between the wars, who spent the night of 2 January in the natural rock bivvy beneath this giant boulder, before perishing in the snow as they attempted to walk back to civilisation. Afterwards, a procession of people came morbidly (says Nan) to read the boys’ account of their last night on Earth, written in the visitors’ journal kept beneath the stone. There is still a Cairngorm Club visitors book there.

-

Above, the Hutchison Memorial Hut, sitting at 2,500ft in Coire Etchachan

The Hutchison Memorial Hut, the Cairngorms

From there it is a steep walk to Loch Etchachan and then a descent into Coire Etchachan to find the Hutchison Memorial Hut. This is one of the few purpose-built shelters in the Highlands, erected in memory of celebrated Aberdeen geologist Arthur Gilbertston Hutchison who died in a climbing accident in 1949.

Staying in the hut for the night was statistician Jiayi Lui, a Scottish resident originally from Beijing. A keen climber, runner and open water swimmer, she is new to bothy sojourns, but says, “It opens up a new way of trekking in the Scottish mountains.”

-

Adrian Pedley, who has been using the Hutchison Memorial Hut as a base for climbing the Munros, with Jiayi Lui (sitting)

Adrian Pedley, a project manager from Manchester, has been using the hut as a base for climbing the surrounding Munros. Formerly a professional outdoor guide, Adrian has caved, climbed and skied all his life. It was his first visit to the hut, and he said, “I’m staying for two nights, and I’ve met two great sets of people and had enlightening conversations. It’s great fun.”

Lairig Leacach Bothy

Lairig Leacach is on the old drovers’ road linking the Great Glen with the south. It has been maintained by the MBA since 1977 and is popular with walkers and cyclists who travel through the pass or are climb the hills in the Grey Corries range.

Experienced Munro bagger Dillon William Simpson was visiting his first bothy. “It’s fantastic,” he says. “It’s a really accessible way for people to enjoy the countryside and the outdoors. It’s very comfortable and I had good company – I didn’t expect to be sharing with 10 or so people.”

Among his companions was Harris Wedderburn-Scott, a merchant navy officer from the Borders and a keen walker and wild camper who was hunkering down for his third bothy stay.

Ruigh Aiteachain Bothy, Glenfeshie

A bothy for beginners, Ruigh Aiteachain has associations with 19th-century landscape painter Sir Edwin Landseer; a replica of his famous stag-head painting, Monarch of The Glen, hangs in the hut. The building has been recently renovated by Glenfeshie estate landowner Anders Povlsen.

-

Lindsay Bryce, who formerly worked in the oil industry, has been staying in bothies for 60 years and describes them as ‘utterly magical’. He is the unofficial keeper of the Glenfeshie bothy

-

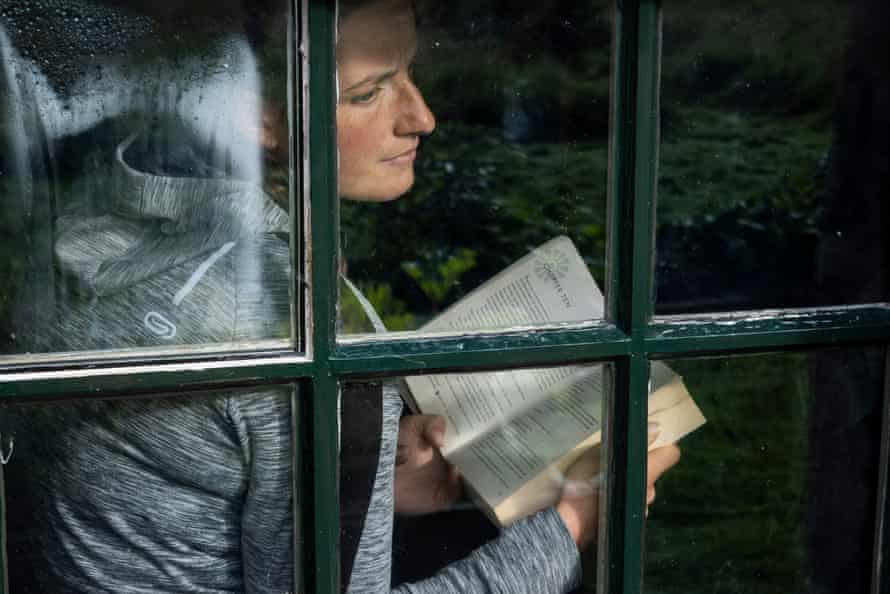

Hannah Dunn, a former aerospace engineer, has been living in her car since March, travelling through Wales, Yorkshire, the Lake District and the Highlands. ‘I’ve only stayed in a handful of bothies,’ she says, ‘but I’ve fallen in love with Scotland and it feels like home now’

Glenfeshie was Craig Harkness’s first bothy stay, and he says: “I’ve been spoilt for choice. It was almost like a B&B – Lindsay made me tea when I arrived and coffee in the morning. It’s been a really nice experience.”

Grace Maycock, a horticulturalist at an organic market garden in East Lothian, has previously stayed at a bothy in the Orkneys but said Glenfeshie was much more comfortable.

-

Above, Mark and Adam Noble, father and son, at Ruigh Aiteachain Bothy in Glenfeshie; right, Mark and Adam beside the replica of Sir Edwin Landseer’s famous Monarch of the Glen painting

Adam Mark Noble, a paramedic living in Nethy Bridge and a former outdoor instructor, was taking his dad, Mark Noble, on a 60th birthday mountain bike trip through the glen.

Tomsleibhe Bothy, Glenforsa, Isle of Mull

On 1 February 1945, a wartime Dakota flying from Montreal via Reykjavik crashed into the side of Beinn Talaidh, 200ft below the summit. Three of its eight passengers were killed. The propeller remains as a memorial outside the Tomsleibhe Bothy, Glenforsa, on the Isle of Mull.