A thunderstorm in Colorado sent the two college students racing for cover down a mountain ridge. A black bear charged at one of them in Washington state. A wildfire’s flames spurred a harrowing escape in Northern California. And a raging infection waylaid the travelers for days in the Wyoming wilderness.

While much of the world was locked down during the first year of the pandemic, Jackson Parell and Sammy Potter were busy planning their escape. The Stanford University students had weathered shared coronavirus infections and quarantines. And after spending months cooped up in online classrooms, they were itching to break free.

So they hatched an ambitious plan: to hike three of the nation’s most arduous trails — the Appalachian, Pacific Crest and Continental Divide — all in a single year.

Jackson Parell signs the Pacific Crest Trail logbook April 4 at the southern terminus near Campo, Calif.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

The two meticulously planned their trip, tracing their projected paths along the country’s most difficult terrain. They transformed the ground floor of the Parell family’s New Hampshire cottage into a situation room, taping paper maps to the walls and stockpiling boxes packed with trail provisions. They saved roughly $25,000 from summer jobs, internships and Stanford research projects to fund the trek.

“At the end of the day, there was a lot that went into this that had nothing to do with our will and desire for it to happen,” said Parell, 21. “A lot of it had to do with the luck and privilege that we’ve been blessed with.”

In the fall of 2020, they began working out twice a day to build up strength for a journey that would take them more than 7,000 miles, from snowy climes in the Eastern U.S. to desert pathways in the Southwest and lush forests in the Pacific Northwest.

The trek, dubbed the Calendar Year Triple Crown, has been conquered by fewer than a dozen people. Potter and Parell set out to be the youngest known hikers to accomplish the feat.

But on the trail — as in life — things happened.

Parell makes his way across the Kennebec River in Caratunk, Maine, on May 21.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Appalachian Trail

With trimmed hair and wide smiles, Parell and Potter set off on New Year’s Day from Springer Mountain in Georgia, in a misty rain.

The Appalachian Trail runs through Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire before ending at Baxter State Park in Maine.

As East Coast natives — Potter is from Maine, Parell from Florida — the two hikers adored the ruggedly beautiful mountainous trail, even in the winter weather that accompanied the early stages of their ambitious journey.

Their days began to take on a familiar rhythm. Waking about 5:45 a.m. and munching on oatmeal or bagels, Parell and Potter would hoist their packs, which weighed more than 20 pounds each, and start walking.

The pair, who adopted the trail names Woody and Buzz, would cover an average of 27 miles a day, excluding “zero days” when they went off-trail to rest and resupply. Breathtaking views, the kind that command the attention of day hikers, bled together, but Potter and Parell still relished their surroundings.

“We’ve seen a lot of stuff this year, and our portfolio of views has definitely filled out. The thing is, I think it’s always just so nice to make yourself stop and appreciate a view,” Parell said. “Because we’re moving so much that those few seconds or minutes that you just get to … take in what’s around usually end up being really special.”

Each day brought a fresh set of delights, as well as challenges. A cool river could refresh their aching feet and legs, but craggy rocks could threaten a twisted ankle.

Sometimes they adopted different paces, one hiking a mile or more ahead of the other for part of the day before reuniting at night. A day’s journey would typically not stop until after 8 p.m., when they would set up camp. If they were near a water source, the friends brushed their teeth or took a cold bath before zipping into their tents — one in winter, two in summer. Once tucked in, they plotted the next day’s course, journaled and sent a quick message to their parents on satellite phones: “I’m stopping here xo love you.”

Parell, left, and Potter prepare for bed May 20 in a lean-to on the Appalachian Trail near Caratunk, Maine.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Soon after, they were asleep.

Less than a month in, Parell and Potter were battling near-zero temperatures, barely talking to each other through frozen lips.

The first few miles on trail were foggy and cold, but soon rays of sunlight began to cut through the mist. I was listening to the daily [New York Times podcast] — about president Biden’s inauguration and his first few executive orders — but it was hard to imagine, as light dripped like honey from branches and dead leaves, that anything but this mattered or was even real at all. The world I was hearing about and the world I was experiencing seemed too different, too detached to exist simultaneously.

Entry from Jackson Parell’s journal, Jan. 22, Saunders Shelter, Va.

By sunset, they had reached the highest point in Great Smoky Mountains National Park but stayed long enough only to take in the expanse of Tennessee and North Carolina from Clingmans Dome. Dehydrated and almost hypothermic, the hikers trudged along, nearly delirious. Both assumed they were farther along than they were, insisting they had seen trail signs that didn’t exist. Potter thought he saw someone on the path but didn’t say anything.

They pushed ahead, determined to reach a trail-side bathroom they had charted, where they bedded down amid the smelly stalls.

“I just remember thinking after that day, wow, like, we really live in extremes,” Parell said. “You just swing from having one of the prettiest sunsets of your life to sleeping in a public restroom the same day.”

A dozen park rangers swooped in the next morning to kick them out of the public facility, as a small boy, waiting for his father to finish his business, peered warily at the sleepy hikers packing up their makeshift camp.

The hikers in Baxter State Park in Maine on May 27, left. At right, Potter greets his mother, Dina, in Monson, Maine, on May 22.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Back on track, Parell and Potter were soon greeted by a “trail angel,” a volunteer who helps long-distance hikers. With gifts of breakfast from McDonald’s, Gatorade and a new camp stove, their energy and spirits were renewed.

But it wouldn’t last long.

Their initial trek abruptly stopped at the end of February, after they covered about half of the roughly 2,200-mile Appalachian Trail. Harsh weather forced them off the snowy trail in Pennsylvania and prevented them from completing the hike in one straight shot.

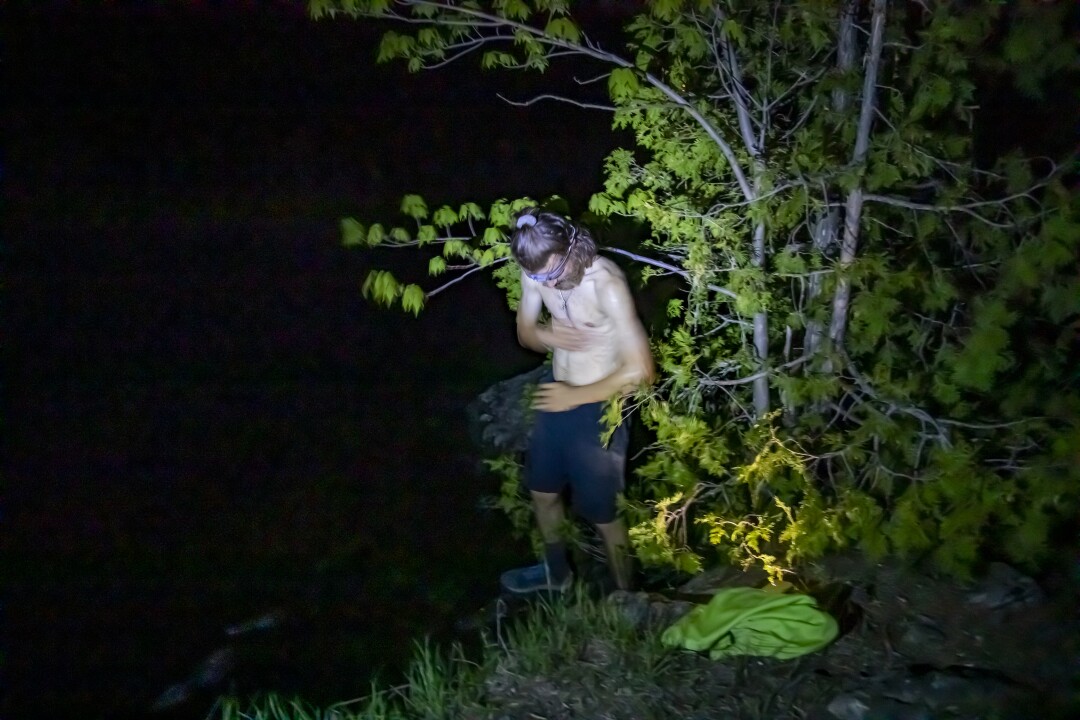

Potter washes in Harrison Pond near Caratunk, Maine, on May 20.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“Doing that and sticking exactly to the schedule is detrimental in the long run,” said Potter, 22. “What’s actually good in the long run is to stay measured … and just be happy.”

To maximize their time in favorable weather on each trail, Potter and Parell hopscotched across all three, beginning a section and then going back to complete the route in better conditions. Each time they returned to a trail, they picked up where they had left off, connecting their footprints across the country.

Parell hugs his mother, Nora, as he and Potter prepare to leave the Berthoud Pass trailhead near Idaho Springs, Colo., Aug. 6 on their northward trek on the Continental Divide Trail.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

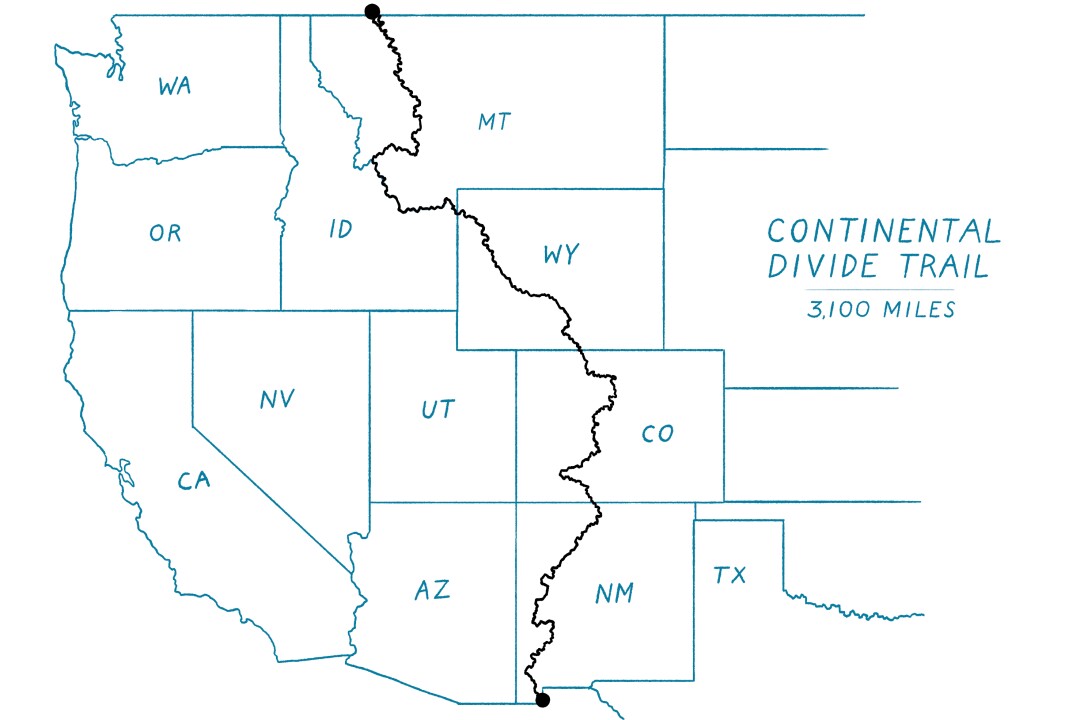

Continental Divide Trail

They rerouted from the Appalachian Trail and flew to the warm Southwestern desert on the Continental Divide Trail, which, at its longest point, traverses roughly 3,100 miles from Mexico to Canada. The full trail runs through New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho and Montana and can be tackled using some shorter, alternate hikes, shaving a few hundred miles off the overall trek, which is “what makes that trail special and unique,” Potter said.

The Continental Divide Trail, with its extreme temperature swings, brought new quirks and challenges. During one stretch in New Mexico, a stray donkey followed the hikers for about 10 miles. At another point, red-and-white spots started spreading up Parell’s arm. Instead of a 150-mile drive in a trail angel’s car to the closest hospital, he opted for the helper’s homemade herb salve. The malady was gone the next day.

In Colorado, storms followed the two almost daily. Clambering up a mountain near Idaho Springs, Parell recalled seeing dark clouds gathering in the distance. Within 10 minutes, the storm was overhead. Jagged lightning started cutting across the open ridgeline. As the tallest figures on the mountaintop, Potter and Parell knew they had to run for cover.

“You really have to keep going,” Potter said afterward. “If you try to bail out on one of those side trails or something, you’re probably just going to get yourself into more danger. It was definitely a tough call in the moment whether to keep going or not, but eventually … we just had to get there.”

Holding tight to their packs, they raced nearly two miles downhill.

Parell laughs as his mother, Nora, tries to persuade him to wear a scarf to protect his head from the sun on the Berthoud Pass trailhead near Idaho Springs, Colo., on Aug. 6. Potter does laundry Aug. 5 in Silverthorne, Colo.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Parell’s mother, Nora, was meeting the young men on the trail that day. Hot from their sprint down the mountain, the two melted into her arms.

“I’m so glad you’re here,” Parell told her.

The hikers gorged themselves on sandwiches, muffins and brownies she had brought. Parell rested briefly in his mother’s car before he and his hiking partner collected their things and set off again.

“It’s not that he looks older — he truly sounds older, more composed,” Nora Parell said of her son. “He has clearly gained a more mature outlook on his own physical being, on … the world around him and what’s happening, and how he wants to step forward.”

To be honest, thinking less and less during the day. Maybe because of cold? Not sure why. Mind wasn’t blank, but it wasn’t filled. Perhaps just preoccupied with river crossings. So many damn river crossings.

Entry from Sammy Potter’s journal, March 2, Gila National Forest, N.M.

Potter and Parell burned through calories faster than they could shovel food into their mouths. In the months before they embarked, the two stocked up on provisions and identified towns with post offices where their families could ship boxes of food to them.

But almost half of the airtight bags they had stuffed with rice and beans, tortillas and other fare broke, leaving their food covered in mold. It ended up being easier to restock at general stores and groceries along the way, occasionally exchanging calorie-rich trail food for more enjoyable treats.

Once summer started, they ditched their camp stove. Hot mashed potatoes mixed with cheese and deli meat gave way to protein bars and almond-butter-and-jelly sandwiches. They reverted to cold-soaking their instant potatoes and rice — mixing dehydrated food with water in a bag and letting the sun bake it as they hiked. Parell lost about 30 pounds.

They tried to stay clean and healthy, stopping as often as they could at laundromats to empty their tattered knapsacks, filled with weeks-old dirty clothing and sleeping bags, into washing machines. They purified water from rivers, ponds and puddles using filters.

Potter changes socks Aug. 5 during a break on the hikers’ journey above Silverthorne, Colo.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Still, while the hikers were on the Continental Divide Trail in Wyoming, Potter’s energy began to drain. Stomachaches plagued him almost daily, and his health began to falter. Usually optimistic, he was waking up every morning for “almost a month, and just kind of dreading the day” — the closest he could recall to ever wanting to quit.

They entered a stretch of trail in August far from a major road. About 10 miles in, Potter vomited.

Parell tries to get warm in the car his mother drove to meet the hikers near Idaho Springs, Colo., on Aug. 6.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“Do you think you should go to urgent care or try to get to a hospital?” Parell asked his trail mate, conscious of the remote section ahead.

“No,” Potter said.

But an hour later, he heaved again. They backtracked about a mile and called a trail angel to bring them to a nearby clinic, where Potter was diagnosed with an E. coli infection and giardiasis, both of which can be caused by drinking contaminated water. After a few days on antibiotics, he was back to his old self.

“We’ve definitely had some bad moments. But even in those moments, like, you still feel really purposeful,” Potter said. “The beautiful things are still beautiful. The special things are still special.”

Potter and Parell prepare for a night’s rest April 2 near Mount Laguna, Calif., in Cleveland National Forest along the Pacific Crest Trail.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Pacific Crest Trail

The two carefully tracked their trip, marking every mile on maps and posting regular updates to Instagram, where they collected a sizable community of online supporters.

Micah Cotton, a 26-year-old bartender in Etna, Calif., followed along virtually as the hikers trekked from one trail to the next. As the weeks and months passed, Cotton watched as Potter’s beard filled in and Parell’s shaggy blond hair was pulled back in a ponytail.

An outdoorsman who aspires to complete a through-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail next summer, Cotton was enthralled as Potter and Parell described the good, the bad and the ugly of the trails on their regular “snack chat” videos.

Potter, left, and Parell brush their teeth after a dinner of mashed potatoes April 2 in California’s Cleveland National Forest, along the Pacific Crest Trail.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“Having the confidence to go after something massive, despite maybe not fully understanding every aspect of it, is the spirit of adventure,” Cotton said. “It was fun to watch in real time because there was a level of … are these guys going to do this?”

There were times when it didn’t seem like a sure thing.

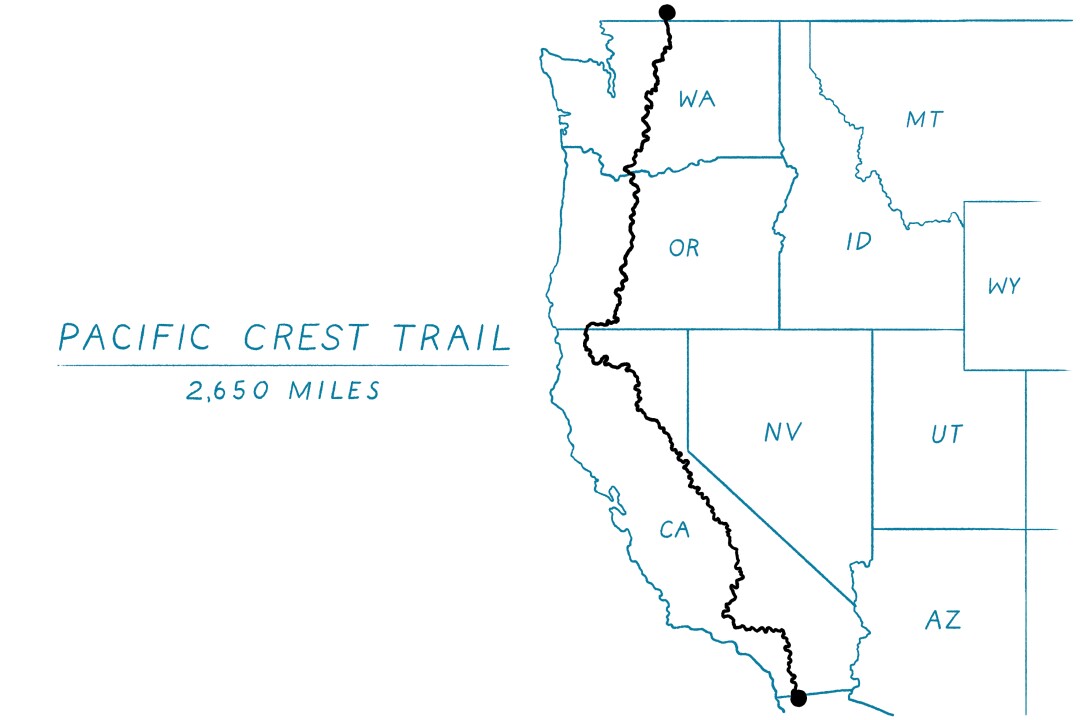

One July day near Etna, a thick haze descended on the two hikers. It was their second time on the Pacific Crest Trail, which runs 2,650 miles through California, Oregon and Washington. They were working their way north from Kennedy Meadows, east of Sequoia National Park.

Potter didn’t think much of the conditions, pressing on. Farther back, though, Parell was stopped by authorities at the closest trailhead.

Lightning storms had sparked a growing wildfire, and officials were closing the rest of the trail — where Potter was hiking. A sheriff’s deputy was evacuating people from a nearby camp.

Parell sent increasingly frantic messages to Potter on his satellite phone.

Parell prepares a dinner of warmed mashed potatoes, salami and cheese in Cleveland National Forest on the Pacific Crest Trail on

April 2. At right, he washes his feet after a day on the trail in Plumas National Forest near Little Grass Valley, Calif., on June 23.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“The feeling of uselessness that I had in those 30 minutes,” Parell said, his voice trailing off. “You never know how fast those fires actually move. … I was terrified.”

Potter had no idea of the operation unfolding below him. He kept going until the smoke thickened into a wall. Eventually, Parell’s messages flooded into his phone.

Unsure of how close he was to danger, Potter climbed several feet up a ridge to peer over the side and was greeted by patches of flames below. He scrambled down and began to run. Pulling out his phone, he started recording voice memos, he said, “in case I died.”

He sprinted nearly four miles back to the trailhead and a fearful Parell. Another trail angel, Derek Whitley, picked them up along with other stranded hikers and brought them into town.

Parell, left, gets a fist bump from a fellow hiker wishing him luck outside a country store near the Pacific Crest Trail in Sierra City, Calif., on June 22.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“That’s what we’re here for — to be the invisible supporter, to be the brightness in their day,” Whitley said. “It’s just our way of doing the old ‘pay it forward’ — we just never ask for it back.”

The roles of trail angels vary. Sometimes, they hand out snacks or drop “trail magic” — surprise gifts in the woods. Other times, they drive hikers from one trailhead to another or serve as a backup in case of emergencies.

Jim Hagan, 59, known on the Pacific Crest Trail as “Legend,” has been helping hikers for decades. He set up camp for a few months at the trail’s southernmost part in Campo, Calif., to encourage hikers. He had just made a big pot of spaghetti when he spotted a weary Parell and Potter approaching. He handed each a beer, and the three sat on picnic tables, swapping trail stories for a couple of hours.

Parell, left, and Potter take in the view of Crater Lake near Klamath Falls, Ore., along the Pacific Crest Trail on Oct. 19.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“At the end of the day, you have to remember, the only two people who really cared whether they made it was those two guys,” Hagan said. “I think when they set a goal like that and achieve it, it sets them up for greatness in life.”

Potter’s mother, Dina, agreed that the trail is “almost like a microcosm of life.”

“I think I’m even more impressed by the adaptation of having to deal with some really difficult things physically, emotionally, because of weather, animals, maybe some disappointment about having to jump trails, but then rerouting with just a really calm and positive demeanor,” she said.

But one thing she wasn’t so thrilled with was the response she got when, on a September visit to the trail in Washington state, she asked her son: “Have you seen any bears recently?”

Potter, left, and Parell at the Pacific Crest Trail southern terminus April 4 at the Mexican border.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

The day before, hiking about a half-mile behind Parell, Potter had turned a corner and stumbled into the path of a black bear standing on two legs, devouring a bush of berries.

“Hey, bear,” he cooed, trying to calm the beast and his own pumping adrenaline. “I’m going to leave you alone. Just let me go on my way. I’m really tired.”

The bear — an angry mama with two cubs waiting nearby — charged at him, huffing loudly. Then, almost before he could think, she skirted around him and headed toward a tree and her waiting babies. She stared menacingly as Potter hastily caught up with Parell, who was casually munching on muffins.

“I don’t think either of us are adrenaline junkies, but it definitely is a rush of feeling very present,” Potter said of the occasional life-threatening experiences during their quest.

Parell, left, and Potter take in the scenery on their final steps toward finishing their 10-month journey on Oct. 22 near Etna Summit in Etna, Calif.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

The finish

After wrapping up the Appalachian Trail and completing the Continental Divide Trail, Parell and Potter returned to Etna in October to connect the dots on the roughly 40-mile patch of the Pacific Crest Trail the wildfire had forced them to skip.

In 10 months, the two had walked approximately 7,400 miles. Together, they burned through 26 pairs of shoes crossing 22 states. They developed a deeper sense of self and broke a hiking record in the process.

The friends had one rule they assiduously followed for nearly a year: no talking about the end. The purpose of the trip was the journey, after all.

In the weeks preceding their final summit, the hazy finish line sharpened into focus, powering their steps. They skipped breakfast and dinner, snacking along the trail rather than stopping in the cold.

But as the reality of the end approached, their steps slowed until all that remained were 17 short miles.

Standing on the crest of a mountain road in the middle of Klamath National Forest, Parell’s mother, father and sister waited for the young men to end their long trek in the same misty weather as when they began. Two figures appeared out of the fog. Parell threw up his hands in victory as his family cheered, waving noisy party clappers. Potter pumped his fist.

The two hikers fell in a heap on their packs, clinked celebratory bottles of Corona beer and hugged.

Parell and Potter wondered about their next steps — this time, in the civilized world. After 295 days on the trail together, joked Parell’s dad, Jack, “now you know what marriage is like!”

Jackson Parell is greeted by his sister Shawn Parell after he and Sammy Potter completed their journey at Etna Summit on Oct. 22.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Maybe they’d get into yoga to stretch out their stiffened limbs, Potter mused. Parell thought they might create a mountaineering club at Stanford, where the two will be roommates in January, when they start their junior year.

But both are reflective of how 2021 has shaped them. They’d missed a lot. A trip that began in the throes of the coronavirus ended as booster doses of the vaccine were being encouraged. A new president took office after a historic insurrection. Climate-changed weather took its toll as deadly storms, record fires and catastrophic flooding swept across the U.S.

“This was a very particular time in my life, and I’m so glad that it happened,” Parell said. “I am at peace with being back in civilization, and it will always be there in my life.”

Potter, left, and Parell toast the end of their journey with beer in Etna, Calif.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Potter, meanwhile, is already plotting a through-hike of the Appalachian Trail in a year.

“Frankly, I feel somewhat of an addiction to this type of adventure,” he said. “Every time you get to … the top of a mountain, I always feel like that’s gonna be the one where, now, I’m satisfied.

“But you always just want to go to the next mountain pass.”