A hundred years ago, in what was then the semi-rural farming community of Watts, a 40ish-year-old Italian immigrant laborer named Sabato Rodia bought a little home on a dead-end block by the railroad tracks and starting collecting junk.

The roar and rattle of Pacific Electric Railway red cars was almost constant, but that didn’t bother Rodia. Perhaps he was already envisioning what would become National Historic Landmark No. 77000297, casting its otherworldly spell on such admirers as Charles Mingus, Betye Saar, Buckminster Fuller and Nipsey Hussle. The train traffic might have annoyed Rodia’s wife, but it gave him a daily audience for the building of the wonder we know now as Watts Towers.

Before long, Rodia was filling his three-sided yard with rebar, concrete, wire mesh, broken Fiesta ware and Bauer ceramics, cast-off Malibu and Batchelder tiles, stray shells and bottles. He called the project “Nuestro Pueblo” (which translates to “our town” in English), perhaps as a nod to the neighbors in a mixed community of Latino, white, Japanese American and Black families.

By the end of 1921, his towers were well under way to becoming one of Los Angeles’ most admired and least understood landmarks.

“You got to do something they never got ‘em in the world,” Rodia said, half-explaining himself.

Are those towers the most powerful act of recycling that California has ever seen? Maybe.

A rusted entrance sign shot through a fence with the Watts Towers in the background.

(Thomas Kelsey / Los Angeles Times)

Are the towers open on the centennial of their birth? Officially, no. They have been closed for restoration since 2017, but people still come to marvel at Rodia’s work. The fences around the lot are low, the towers soar nearly 100 feet high, and there’s more to see than the structures themselves.

Here — in 17 reclaimed bits and pieces, like Rodia’s masterpiece — is some of the story.

1. “Flashing Spires Built as Hobby. One constructed by Watts Resident rises to Height of 100 Feet.” — Headline of the first Times story about the towers on Oct. 13, 1937. The six-paragraph article identifies the builder as Simon Rodilla and claims the structures are “modeled after quaint towers which Rodilla remembered from his native Italy.”

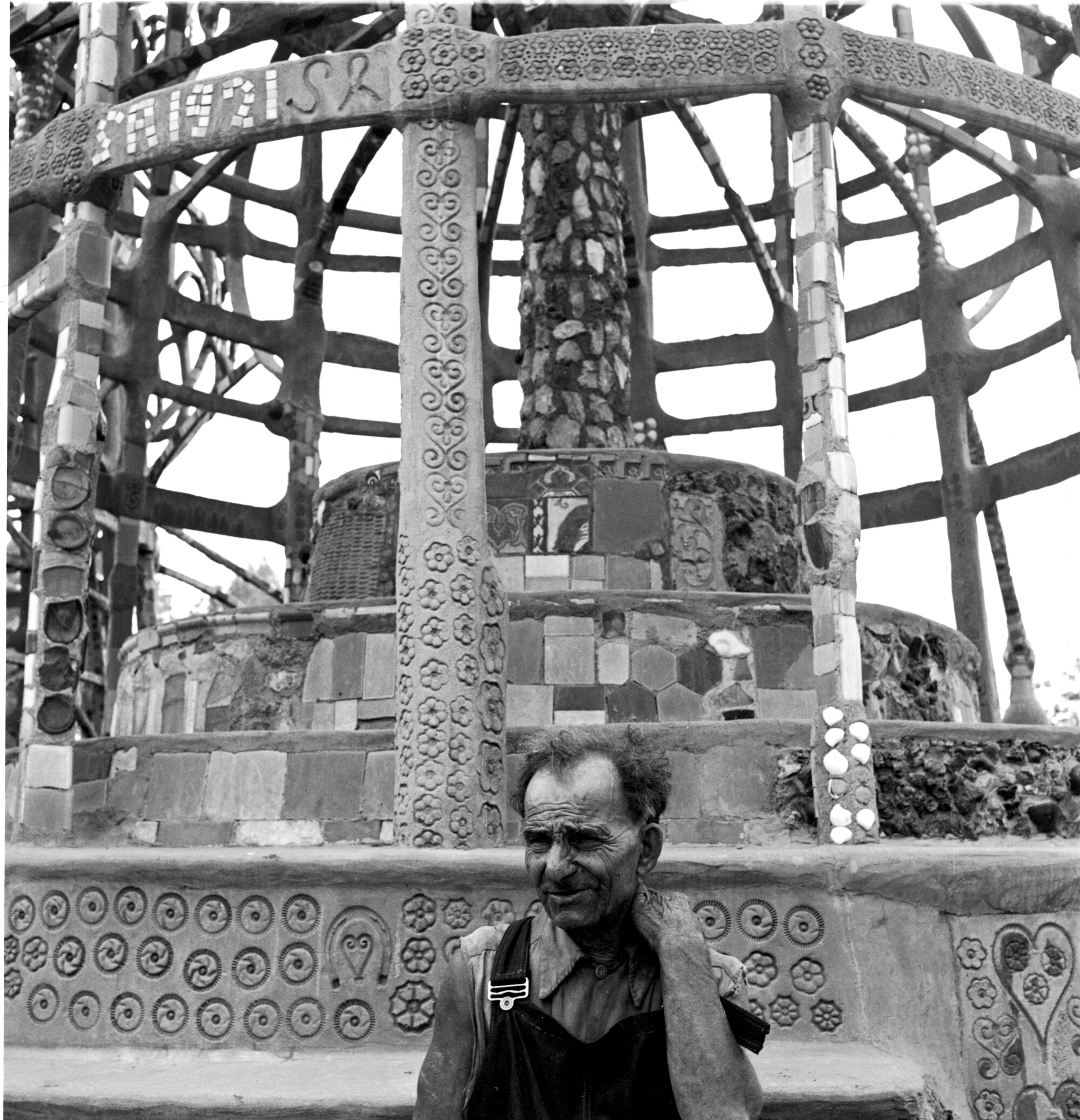

Italian-born American sculptor and designer Simon Rodia at Watts Towers — a monument of steel, concrete and found materials that he constructed by hand over a period of 33 years in Watts.

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

As Mr. Rodia’s “Nuestro Pueblo” grew, Mrs. Rodia quickly departed. This was the third and final broken marriage or cohabitation for him, a man of little education but profound sense of purpose.

He stood 4-foot-10, loved opera, scorned the Catholic church and started the towers soon after quitting drinking. Sometimes he went by Simon, sometimes by Sam, sometimes by Rodia, sometimes by Rodilla.

2.“He had a regular job as a tile setter, but on weekends and at nighttime, under lights he strung up, he was building something strange and mysterious. … He was always changing his ideas while he worked and tearing down what he wasn’t satisfied with and starting over again, so pinnacles tall as a two-story building would rise up and disappear and rise again.” — Jazz great Charles Mingus, who grew up on 108th Street, in his autobiography, “Beneath the Underdog.”

The Depression came and went. World War II came and went. Rodia labored on. The project grew to include three spires, two walls, a gazebo, several small towers and a patio. From certain angles, the whole assemblage looked like a stranded ship with three masts rising above the surrounding sea of working-class bungalows and railroad tracks. The wiry Rodia would climb it like a sailor in rigging or a spider in a web.

3. “I think I was three years old and my mother [artist Betye Saar] took myself and my sister [artist Lezley Saar], who must have been five or six, to the Towers. We must have been under one of the main towers, and when we looked up it was like a spider web. It was really wonderful for us as kids that age because it was a kind of micro-world where we could get really up close to things. Back then they let you climb on the towers and touch them, which is probably why we need conservation efforts now.” — Alison Saar, assemblage artist, speaking to LACMA’s Unframed blog.

4. “He built the towers by hand, alone, without machine tools, without nails, without scaffolding, without written plans and with no client to absorb the costs. He had no drill and used no bolts to hold together pieces of the steel he used.” — Bud Goldstone and Arloa Paquin Goldstone in book “The Los Angeles Watts Towers.”

Asked what it was all about, Rodia never seemed to give the same answer twice. And then, after 34 years, he bolted. He moved to Martinez, north of San Francisco, where he had a sister.

By then Rodia was in his 70s. Watts had become a mostly Black neighborhood, with far more density, poverty and crime than in the 1920s. Was he just tired? Fed up with vandalism by local kids? Dismayed by the dwindling rail traffic rumbling past his masterpiece?

Again, never the same answer twice.

5. “When he finished the towers Sabato Rodia gave away the land and all the art that was on it. He left Watts and went away, he said, to die. The work he did is a kind of swirling free-souled noise, a jazz cathedral … .” — Don DeLillo in his novel “Underworld.”

6. “He was not happy with the way elected officials ran the U.S. government. He was not happy with the way mothers treated their children or with how American children acted toward their parents. He was not happy with the way police abused immigrants. He was not happy with the image afforded his favorite historical heroes, Marco Polo and Christopher Columbus among them.” — Bud Goldstone and Arloa Paquin Goldstone in “The Los Angeles Watts Towers.”

Italian-born architect Simon Rodia climbs a spire of the towers.

(Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

7. “In 1956, Joseph Montoya bought the Towers … for a reported $500. He had the entrepreneurial aspiration of turning them into a taco stand.” — Jeffrey Herr in book “Sabato Rodia’s Towers in Watts: Art, Migrations, Development.”

By year’s end, the taco stand plan had fallen through and Rodia’s old house had burned down.

In a bid to protect the site, filmmaker William Cartwright and actor Nicholas King agreed to buy it for $3,000. Then, writes Luisa Del Giudice in “Sabato Rodia’s Towers in Watts: Art, Migrations, Development,” they formed the beginnings of the Committee for Simon Rodia’s Towers in Watts, an assemblage of activists, art experts, architects, engineers and attorneys that would fight for decades to preserve the landmark and promote education and the arts in the neighborhood.

One of the first things Cartwright and King found, however, was that in 1957 the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety had issued a demolition order.

8. “Inspections show these structures are dangerous and should be torn down. They were built without a permit, without inspection and without approval of the design.” — H.L. Manley, of the Los Angeles Department of Building and Safety, to The Times in May 1959.

One of the towers’ defenders, aerospace engineer Bud Goldstone, persuaded city officials to leave the towers alone if the structure proved its soundness in a stress test. On Oct. 10, 1959, with a crowd of arts advocates and national media standing by, engineers applied 10,000 pounds’ worth of pressure to the tallest tower — and nothing happened.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

9. “The tower stood and the crowd cheered when the representative of the Department of Building and Safety removed the demolition order sign.” — Jeffrey Herr in “Sabato Rodia’s Towers in Watts: Art, Migrations, Development.”

10. “Simon Rodia’s towers of Watts are articles of faith. His innate genius, it now turns out, encompassed not only an astounding artistic inventiveness but an equally amazing, intuitive engineering knowledge.” — Times art critic Henry J. Seldis, writing on the morning after the stress test.

In the following years, as community leaders and arts advocates looked for a way to work together, the Watts Towers Arts Center was born next door to the towers, co-founded by Noah Purifoy, Judson Powell and Sue Welsh. By the end of the summer of 1965, many other parts of Watts had burned in a Black upwelling of antiracism protests and riots that led to 34 deaths.

But the towers survived.

And Purifoy and Powell set out on their own mission of neighborhood reclamation, combing the charred area to collect debris that they crafted into works of art to evoke the uprising. Their exhibition, “66 Signs of Neon,” toured museums and colleges nationwide.

That same summer, Rodia died in Martinez, having never returned.

11. “If a man who has not labeled himself an artist happens to produce a work of art, he is likely to cause a lot of confusion and inconvenience.” — Calvin Trillin in the New Yorker, shortly before Rodia’s death.

12. “Hail to the innocent Gaudi of California, who destroyed the myths of Disneyland and movie-land in a swift, isolated competition.” — Italian sculptor Gió Pomodoro.

13. “I think Sam will rank, not just in our century, but will rank with the sculptors of all history.” — Architect and inventor Buckminster Fuller in the 2006 documentary “I Build the Tower.”

These days, the towers are protected as a state park and under conservation through a city contract with the L.A. County Museum of Art. Next door, the Watts Towers Arts Center operates a gallery, a garden art studio and arts classes for youth and adults. Every September, in nonpandemic years, the center co-hosts jazz and Day of the Drum” festivals.

Meanwhile Watts keeps changing. Census figures show the community is now about 80% Hispanic and 18% Black, still densely populated and beset by poverty and crime.

::

For most of the last two years, the towers have been boxed in by scaffolding as a LACMA-led team of conservators labors to seal cracks in the cement and reinforce their steel armature.

“The towers actually move. In the day they expand and at night they contract,” said Rosie Lee Hooks, director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, who has worked at the site since 2003.

Because of Rodia’s improvised construction process, Hooks said, “conservation and preservation will always be needed for the Watts Towers. Every 10 years or so, we do major scaffolding.”

Bits and pieces of shells add to a collection of 17 interconnected sculptural towers, individual sculptural features, architectural structures and mosaics located on the site of the artist’s original residential property.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

14. “Although in my heart I know that we are doing something really amazing, because we are trying to preserve this monument for the future generation, somehow, knowing his personality, I think he wouldn’t completely be okay with it . — Conservator Elisabetta Perfetti, in LACMA’s Unframed blog.

The most recent scaffolding came down in November. Though the ground-level area inside the towers remains fenced off, visitors arrive daily. They walk around the structures or look at the arts center’s murals or browse the garden studio, which includes sculptures and a turtle pond with scores of turtles and an African tortoise.

Hooks calls the arts center “the guardian of the towers” and laments that some visitors seem more interested in the neighborhood’s traumas than in the many celebrated artists who have found inspiration and built skills at the foot of the towers.

“We are not 1965, so don’t come looking for 1965 or 1992,” said Hooks, referring to the unrest after the Rodney King verdict. “We have contributed more to the world than that. And we continue to contribute more to the world than that.”

Beyond Rodia, Purifoy and Powell, the list of artists connected to the towers includes several more who work in assemblage, including John Outterbridge, who directed the arts center from 1975 to 1992; Betye Saar and her daughters Alison and Lezley Saar. The late rapper and philanthropist Nipsey Hussle took music classes at the arts center as a teenager.

“There were teachers, volunteers, who taught the kids how to make beats and how to record themselves. And it was free,” Hussle’s brother Samiel Asghedom told The Times two years ago. “That’s something Nip and a lot of people successful in music now went to as children. He took that small opportunity and ran with it.”

After Hussle’s shooting death in 2019 at age 33, neighbors built an altar at the towers.

15. “When I see those towers soaring over Watts, my thoughts always return to the pieces that make up that beautiful whole. To the value in those things that people, in their haste, are so apt to cast away.” Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa in his inaugural address, July 1, 2005.

16. “Rodia’s birthplace, Rivolati, is very near the town of Nola, in Campania, near Naples. Here Rodia’s artistic imagery was inspired by his childhood exposure to the great ceremonial towers, some six stories high and weighing over three tons, carried in the Giglio festival… — National Register of Historic Places listing for the towers.

17. “Think of that little guy, all by himself. Not a penny from it, not a penny. We don’t have those people anymore. After I saw the towers, I wrote a prayer about them. It’s a miracle. A thing like that … it happens once in a million years.” —Italian American sculptor Benny Bufano.

Times library director Cary Schneider contributed to the research for this article.