Warrington

It’s not so much a mist as a murk, a weakness of light due to the late season and lowering sky. Mirroring the grasping hands of wintry trees are bare branches plunged into still water, in turn reflected there. I think of flooded forests on the upper Amazon. I’m in Warrington. If the juxtaposition seems silly or funny, that’s not my problem.

I’ve come to take a circular walk along the Mersey and the Manchester Ship Canal, two great watercourses almost universally ignored – certainly by travel writers and tourist boards and, from the evidence of the empty footpaths, by Warringtonians too. It’s a Saturday afternoon. No doubt the locals are largely seated beside their hearths, perhaps reading the glossy supplements, surfing the net, wondering over a holiday away from the pandemic pandemonium and the pall of December.

Most of the travel we choose is chosen for us – at best by past adventurers, more usually by tour firms devoted to cliche and consumption. I’d bet Warrington is less attractive to most British passport holders than Ulaanbaatar, Bilbao or Cancún – despite those places being, respectively, poorer, more industrialised, more dangerous. Capitalism, the Crap Towns crowd and all those unfunny-as-hell websites have made much of the UK unfashionable, undesirable and uncool.

Yet a minimal effort uncovers Warrington’s secrets: the statue of Cromwell, whose forces overcame the Duke of Hamilton’s Royalists and Scots in 1648; the Academy, where Joseph Priestley, discoverer of oxygen, worked and which once made the town the “Athens of the North”; the Bank Quay factories that turned us into a nation of sweet-scented soap users; one of the UK’s last transporter bridges; and Warrington Bridge itself, on the old Roman road, once a portal to a swampy nowhere, then to Northumbria, Lancashire and, post-1974, a dubious corner of Cheshire.

As for the walk, well, you get to see the glorious Mersey, which meanders wildly here at its shallowest stretch; the Woolston Cut (now an ecology trail) was built to shave off a great loop. You see the ship canal, the precursor to those of Panama and Suez (where you’d no doubt love to take a holiday). I see a cormorant skimming, a stork rising like an old C-54 Skymaster from nearby Burtonwood, and a huge raft of tufted ducks by the weir, dabbling and drifting. I hear the hum of the M6; transport is everywhere in the north-west. Above all, I feel, in the gloom-hued canal, the rushing river, and in the great iron girders and steel spans of rail and road bridges, the weight and tow and flow of history.

At the Barley Mow pub, built in 1561 and a rare Tudor trinket in a town obsessed with rebranding, regeneration and, above all, demolition, I toast Warrington’s wonderful absence from Unesco’s or any other sappy heritage list. Overtourism? It’s not a problem. It’s just you, on your holidays, with everyone else.

Blackburn and Darwen

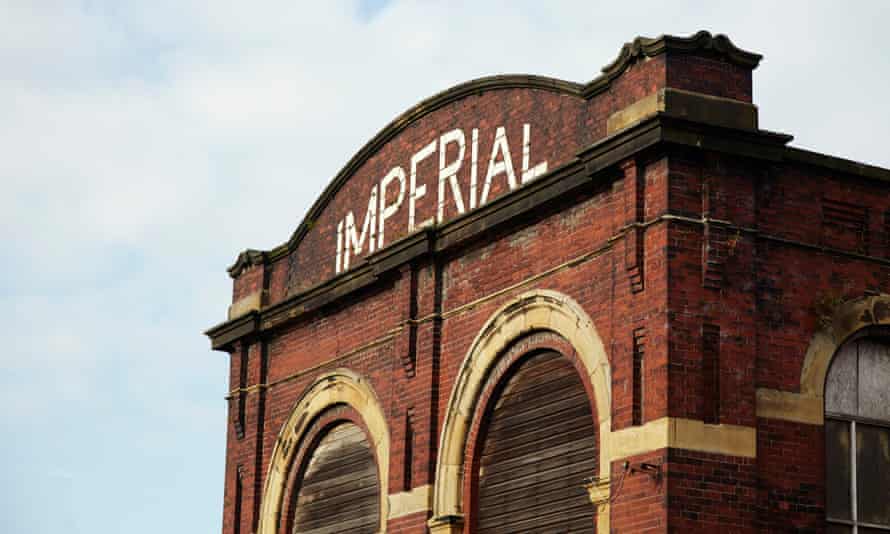

Mill towns would have done well to keep more of their mills. On Gorse Street, Blackburn, Imperial Mill, built in 1901, is a redbrick beauty. It would have been truly wondrous if they hadn’t felled the chimney in 1958. The facade of Waterfall Mill on Peel Street is lofty and dignified. Again, no chimney. Like a house without windows. No hope of resurrection. I walk the A666 (the Devil’s Highway – perhaps the road where the “4,000 holes” of A Day in the Life pocked the blacktop) into Darwen, and stop at the junction with Spring Gardens. India Mill still has its chimney, at more than 92 metres one of the tallest in Lancashire; today the building’s “open plan suites are available for office, leisure and storage”. Better than the wrecking ball, anyway.

Such solidity, such fearless symmetry: I am more moved by textile mills than by any Taj Mahal or Angkor Wat. Why? Because their shadows are internal and external, and if you are a northerner, that’s where you still walk. If you are a southerner, consider: these paid for your gherkins and your cheese graters.

Long before he became a national treasure cum caricature associated with the Cumbrian fells and other hiker honeypots, Alfred Wainwright was an anonymous Blackburn native, Rovers supporter and tramper of the less-exalted heights of Darwen Hill and the lowland pastures of the Ribble Valley. A 126-mile Wainwright’s Way, devised by guide and author Nick Burton, links Blackburn to Buttermere: a journey from truth to fiction. If you’re after a shorter ramble, try the 4.5 mile walk, by way of the Wainwright Memorial (and troposcope, a directional circle giving distances to landmarks) on the Yellow Hills. On a clear day you can see the summits of the mountains the great man would scribble about and sketch.

According to Panorama in 2007 and again in 2018 – someone had a point to make – Blackburn is Britain’s most divided town. But the fact that this city is 27% Muslim surely makes it fascinating as well as fractious. Clock the 30-odd mosques, with their minarets – their chimneys for the djinn, perhaps. Morocco has been a must-visit destination for too long; do something original, swap the Atlas mountains for the west Pennines, and visit your very own Marrakech-on-the-Moors.

Surbiton

One of the strangest things about the London hipsterati is that they haven’t moved on from The Good Life (1975-8). Still, they insist, “Surbiton, bah, boring, square, Surrey.”

Though filmed in Northwood, north-west London, the TV series was set in a fictional Surbiton – a byword back then for middle-class commuterland. The name even looks like “suburb”. But it was a joke, or perhaps a trick to fool the obtuse. For this Thames-side town in London’s zone six harbours more easily accessible joys than many supposedly happening districts in the capital’s inner boroughs – and it does so with none of the gloating self-satisfied superiority of nearby Richmond, Kew, Barnes and Wimbledon.

The landmarks start as soon as you alight, for Surbiton station is a poem in reinforced concrete. Built by James Robb Scott in the 1930s in art deco style, its straight lines and whitewashed plainness suggest both an Odeon cinema and a mausoleum. Stepping away from this portal to the Smoke, we soon find ourselves on leafy lanes and stately avenues lined by lofty Georgian townhouses, Victorian terraces (the St Andrew’ Square Conservation Area could grace Belgravia), 30s deco-influenced blocks and to-be-expected Tudorbethan detached houses. Village-type pubs and restaurants punctuate the quietly elegant residential streets.

This continues all the way through the Seething Wells area – an unhappy corruption of the original name, Soothing Wells – to the marina and riverside, where a path leads to Kingston, across the bridge, and into Home Park – the nicest of the royal parks, with ancient meadows, floodplain ecosystems, a superb fallow deer herd and the Long Water – the original neighbour-impressing “water feature”, built by Charles II in 1660 as a wedding gift for bride-to-be Catherine of Braganza. Hampton Court is at the far end of the geometrical pool, should you wish to join in the melee of stately home-ites and Wolf Hall fans.

Birkenhead

Visitors to Liverpool swarm to the waterfront to see the Three Graces, but they are so big, so imposing and so close that they lead only to neck cricks and distorted photographs. Look, instead, to the muddy, maudlin Mersey – so quiet these days – and the strange oblong on the opposite bank. It looks like a Modernist church. That is where you should go to pray and meditate on Liverpool.

The Pier Head–Woodside ferry runs at peak times Monday to Friday, costs £3.70 return, and takes about 10 minutes to cross.

First stop is the church – that is, the Grade II-listed Woodside Ventilation Station, drawing fumes from the Queensway tunnel as its giant fans push fresh air underground. Designed by Herbert Rowse (also responsible for Liverpool’s Philharmonic Hall and India Buildings) and built between 1925 and 34, it’s a brilliant expression of form meeting function.

Rowse’s Sidney Street and Taylor Street shaft buildings are also on the Wirral and also in staid brown brick, while the better-known George’s Dock building across the water is in Portland stone.

If you need a stretch of legs, the East Wirral coastal trail is awash with maritime memories, from the Camell Laird shipyard, to the U-boat Story (currently being refurbished), to the (probable) steps and jetty of Job’s Ferry – the 12th-century precursor of the trans-Mersey service to “the place I love”. A few paces inland are Birkenhead Priory – the oldest building on Merseyside – and the Georgian masterpiece that is Hamilton Square, second only to Trafalgar Square for the number of Grade I-listed buildings on a single site.

Birkenhead Park, opened in 1847, was the first park to be built with public money. It was laid out by Joseph Paxton, best known for work at Chatsworth House, and offers native and exotic trees, lodges, ponds, rock gardens, serpentine paths, bridges, a cricket crease, “probably the oldest brick-built cricket pavilion in the world” and a boathouse. American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, visiting in 1850, took ideas from Birkenhead when designing Central Park in New York.

Wrexham

Wrexham confounds English notions about Wales – the fantasy island of Merlin and Arthurian myth, the unpeopled Green Desert, and laughingly tying one’s tongue over Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. It’s six miles from the English border – and there is a sense that it might have been better off if it could shirk off the old yoke and shift farther into Cymru.

The most purist form of tourism is to travel in search of nothing, whether that’s a colourful version of empty spaces (Patagonia, Death Valley, the central Asian steppe) or a ghost of what has been. Wrexham, from the latter viewpoint, is quite remarkable, a veritable Paris of what is lost. Highlights of the missed include the former police station, a Brutalist masterpiece that was razed in November 2020; the mock Tudor vegetable market, demolished to make way for a BHS, now also extinct; Manchester, Birmingham and Yorkshire Squares, where trading in textiles, hardware and leather from those respective regions took place.

The General Market (formerly the Butter Market, for dairy produce), built in 1879 in the famous Ruabon brick of this area, is the last edifice to evoke the glory days of Wrexham as a commercial hub. With plans to demolish the old Rhosddu vicarage and 18th-century Moreton pub – despite local protests – the “capital of north Wales” seems anxious to keep emphasising the “wreck” in Wrexham. As they say in the guidebooks, go before it’s gone.

Outside town, things are somewhat more enduring. Clywedog Valley Trail is an easy 5½-mile walk from the 18th-century Kingsmill corn mill (recently saved by a community fundraiser) at the south-east edge of town to the Minera Lead Mines and country park. Do a detour to pay a visit to the National Trust-managed Erddig Hall, a 1,200-acre country park and 18th-century pile. Wrexham is east of Offa’s Dyke, but it’s well worth the trip out to visit this section, as it includes the Unesco-listed Pontcysyllte aqueduct, which carries the Llangollen canal over the steep-sided valley of the River Dee.

Elephant & Castle, London

As Brian, an old friend of mine and long-term resident of the Elephant, likes to say, his barrio is the centre of London. He points me, and everyone else, to the obelisk at Saint George’s Circus – erected in 1771 – where it is clearly announced in stone that it is “One Mile” and a bit to Fleet Street, Palace Yard in Westminster or London Bridge.

But don’t dash off to those well-trodden sites. For the 21st century is happening right here: like it or loathe it, few areas of Britain can compare for scale or style of reinvention. Two decades ago, Elephant and Castle could, for most people, be summed up as two teeming (and, for cyclists, lethal) roundabouts, one ugly yet quirky shopping centre, and urine-perfumed underpasses to test even the most avid of urban psychogeographers. While tourists happily went to Brixton, Clapham Common, even dull old Dulwich, their main interest in Elephant was the fine range of bus services to other places.

But dig a little and the Elephant reveals its tender verities. The Pullens buildings are among the last few remaining Victorian tenements extant in London, which removed thousands of properties during slum clearances in the 1920s and 30s. Behind the elegant terraces are cobbled yards where studios and workshops clang and whoosh to the postindustrial sounds of 3D printers and digital cameras, and neo-artisans and crafters making floral arrangements, ceramics and woodwork.

This district is home to London’s largest Latin quarter, with hundreds of residents originally from Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru and about 150 Latin American small businesses selling anything from tasty ground-maize arepas to classes in salsa dancing or English and Spanish language. Like other residents, they lamented the recent demolition of the Elephant & Castle shopping centre – not for them a symbol of urban decay, but of home from home. The Strata SE1 residential tower (with its famous non-functioning wind turbines), 15-storey Vantage building (one-beds at £1,425 pcm) and the yuppifying of Metro Central Heights, designed by Ernő Goldfinger and formerly occupied by the Department of Health and Social Security, signal a different future.

Elephant, once known as the “Piccadilly of south London” for its commercial, retail and entertainment offering, is joining the rest of Alpha-City London on the high road to hyper-gentrification. What is tourism for if not to see the clamour of the present day and the collisions of past and future?