Five days a week, Ryan Hartson scours the picked-over aisles of Mariano’s in Chicago to fill grocery delivery orders for Instacart. He clocks in for his shift exactly on the hour — if he’s even five minutes late, he’ll receive a “reliability incident.” Within four minutes he must accept any incoming orders; any longer, and he’ll be kicked off the shift and risk getting an incident. Three incidents in a week, and he’s at risk of termination.

“It’s a very easy job to lose,” Hartson said.

To avoid missing orders, Hartson schedules his bathroom visits — after four hours of work, the app notifies him that he has earned a 10-minute paid break. Meanwhile, Instacart managers use the app to see if he’s running behind on his orders. The app also tracks Hartson’s customer communications, automatically searching for specific terms to ensure that he’s using Instacart’s preferred script. If he doesn’t, his metrics will take another hit.

Metrics define the experience of Instacart’s part-time workforce. Measured weekly for employees such as Harston are the number of reliability incidents, the number of seconds it takes to pick each item and the percentage of customers with whom they correspond. Some former and current employees say 5% to 20% of shoppers in a store can be fired weekly.

Even in the data-driven tech world, Instacart stands out for its metrics-oriented culture, interviews with more than 30 current and former employees, as well as documents and recordings reviewed by The Times, reveal. This drive toward productivity helps Instacart’s profit margins, a vital step for a start-up that recorded its first-ever monthly profit in April, as the COVID-19 pandemic heightened demand for grocery delivery.

Instacart says it has eased enforcement of certain metrics during the pandemic, but shoppers say company policies often ignore the realities of the job, leaving them in constant fear of termination over matters that are out of their control.

Instacart says it evaluates shoppers on more than just speed and efficiency. Natalia Montalvo, the company’s director of shopper engagement and communications, said the in-store shopper role was built on the premise of “flexibility, efficiency, innovation and customer service.”

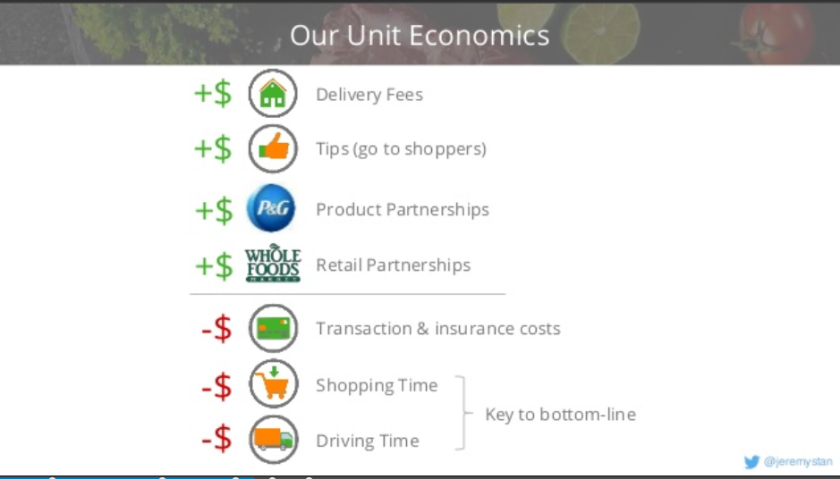

“Efficiency and fulfillment of customer orders in a timely manner is important,” Montalvo said, “but it’s just one of many factors we look at in our overall business health and growth relative to other contributors,” such as revenue derived from advertising for and partnering with consumer brands.

Founded in 2012 among a cohort of venture-backed start-ups purporting to revolutionize inconvenient tasks by making them on-demand, Instacart measured its early success by scale. The San Francisco company expanded rapidly into new markets, enticing workers by turning a weekly errand — a trip to the supermarket — into a moneymaking opportunity. Customers marveled at the ease of use.

“In the early days of Instacart, we were losing money on every single delivery, and we were growing fast,” Chief Executive Apoorva Mehta said in an onstage interview in 2018. “That’s not a good combination.”

But it’s one that’s familiar to many companies in the gig economy, including Uber and Lyft, which have tried to stem losses by raising rates, lowering pay and rolling out new services. To make the unit economics work at Instacart, Mehta realized they needed to better manage the primary cost to the company: labor.

Instacart relies on a combination of in-store hourly employees and contractors; in-store shoppers pick groceries, while contractors can choose to pick and deliver or just deliver. In-store employees receive minimum wage and work a maximum of 29 hours a week — just under the 30-hour cutoff to qualify for employee healthcare.

Core to bringing down the costs “associated with the wages that we pay for the picking and delivery,” as Mehta put it, was speed — time spent finding a specific item — and efficiency — time spent between orders, in line, loading the trunk and getting an order to a customer’s home.

“As we build more volume, we build density,” Mehta said. “With density, each delivery takes less time…. Each minute we save on each delivery is 25 cents in gross margins. When we save that money, we can give that money back to the customer, so it’s cheaper for the customer to make an order on Instacart.”

Facing pushback from shoppers and corporate employees for its singular focus on speed, the company in 2018 said it would begin to incorporate quality metrics alongside those for speed and efficiency.

“Over the last few years, we’ve implemented new tools, resources and guidelines to help shoppers deliver the best customer experience possible,” Montalvo said in a statement. “To achieve this, we expect in-store shoppers to show up for scheduled hours, pick high-quality items, complete orders in a timely manner and provide excellent customer service.”

As the coronavirus crisis flooded Instacart with a surge of new customers, the company added more than 300,000 hourly and contract shoppers and said it would stop penalizing those who fell short of speed and efficiency requirements. Shoppers such as Hartson, however, continue to be graded on other metrics and could still face reprimands for reliability incidents. And they still receive regular reports on whether they meet speed and efficiency targets.

“They’re tracking all this data,” Hartson said. “Will they go back and use this as a pretense to fire people?”

Montalvo said such metrics are for now “purely a personal guide.”

“We believe it’s important that shoppers are aware and understand the significant role they play in delivering a great customer experience, which is why we focus on the details related to each order,” Montalvo said.

Screenshot of weekly metrics given to shoppers at one location in May 2020.

Close management of worker efficiency has become a hallmark of the on-demand tech industry. Companies including Amazon — where Mehta worked on fulfillment systems before launching Instacart — famously police worker productivity in their warehouses.

But compared with a fulfillment warehouse, a grocery store is an unpredictable place. At any given moment, in any given store, the avocados might be overripe, the organic carrots sold out, the fancy olive oil moved from its normal location to a new display. Any of these factors can slow down in-store shoppers and harm their metrics.

It’s not easy to navigate a grocery store under a tight deadline — as anyone who has viewed “Supermarket Sweep,” a recently revived game show, can attest. Some in-store shoppers, including Jonathan McNelis, say the show is not a far cry from their jobs.

“You can literally feel the pressure of time counting down as you are shopping, trying to weave through the aisles,” he said.

McNelis started as a shopper and was promoted to shift lead, a position he held until February 2020.

“At times you are literally running to get one- or two-item orders, because the system only gives you three to four minutes to get the item, get through checkout and stage it before it negatively affects your speed metrics,” he said.

In some stores, Instacart expects veteran shoppers to spend no more than 72 seconds — including standing in line at deli or seafood counters — to find an item or an appropriate replacement if it’s out of stock, sources and documents say. Before the pandemic, slow shoppers were eventually fired, and faster shoppers were assigned more orders, according to two sources and documents and screenshots detailing company policy and metrics reviewed by The Times.

Montalvo said “efficiency and fulfillment of customer orders in a timely manner” is just one factor the company looks at when evaluating “overall business health and growth.”

To this day, speed leader boards are displayed in some break rooms, and the speed of each shopper is included in reports regularly sent to all shoppers in a team Slack channel in some locations. As of February, managers determining whether shoppers should be terminated or coached received data on the number of seconds it took the shoppers to procure each item, a screenshot reviewed by The Times shows.

A slide from a presentation by former Vice President of Data Science Jeremy Stanley.

In an effort to increase speed, some managers held “shopper Olympics” or “shopper competitions,” which encouraged workers to move faster to win a gift card or a mention in the regional newsletter, documents from 2018 detailing recaps from 10 locations over a two-month period show. Managers mentioned speed more than 60 times in those documents. “Shopper speed stayed the same even though we worked more diligently to get it down,” one entry read. Another read: “We hit our new speed targets, thankfully!”

Another challenging metric for shoppers is refunds. If an item or a suitable alternative isn’t available — as was the case at many retailers early in the pandemic — shoppers can face consequences. In some stores, fewer than 10% of orders can include such a refund.

Shoppers are required to chat with customers about the progress of their orders using specific words, or else the chats aren’t counted, and the shoppers’ rankings inside the company may fall. “An algorithm is used to search for certain phrases to calculate chat [metrics],” according to a manager’s Slack message to shoppers.

The company said tools such as “automatic templates” help shoppers provide great service.

“You’re like spinning plates, riding a unicycle,” Hartson said. “You have to go as fast as possible, and you have to be a perfect customer service agent.”

Incidents and low metrics can add up. Hartson said he got a strike for not accepting an order in time while he was helping a customer find something. Another current employee named Hiren, who asked that his last name not be used because he was not authorized to speak to the media, said he talks to every customer, but because he doesn’t use Instacart’s script, his chat metrics show he has spoken to only half. One former manager said if an item is missing — it was left behind by the delivery driver, perhaps — there’s no way to argue that it wasn’t the shopper’s fault.

Shift leads, who oversee in-store shoppers, are similarly judged by metrics, according to five former and current employees and documents reviewed by The Times. Before the pandemic, the push to achieve favorable storewide metrics led them to evaluate, coach and ultimately fire shoppers whose numbers dipped below targets or who had three strikes on a weekly basis, six sources and documents say. Shoppers were often quickly replaced.

In the 2018 document, one shift lead listed “weeding out bad shoppers” as a strategy that worked well. In an entry for planned actions for the following week, another wrote, “double up coaching and [train] out bad shoppers. Hiring.”

The time between coaching and termination and the number of people fired per store depends on factors that include store size and managers’ discretion, according to documents and at least five sources. In McNelis’ region, before the pandemic, shoppers who missed speed or quality goals for up to four weeks straight were terminated.

“You would need to maintain goal for both speed and quality for at least a week to get you off,” he said. “The worst part was if one person only worked one day, for very few hours a week, it was very easy to go out of goal, because they didn’t have enough orders to offset one or two bad orders for their metrics.”

At the four Florida stores McNelis oversaw, one to two people were fired every week out of a workforce of 10 to 15, he said. Managers in some cases simply stopped scheduling shifts for shoppers whose productivity or quality metrics were lagging, three sources said.

Montalvo declined to comment on the rate of turnover but said the company saw a “natural fluctuation in employment,” as any industry would.

She said Instacart relies on shift leads to create the best work environment and encourages them to work with shoppers who have “repeated” issues “to determine the best path forward.”

During an August town hall for in-store shoppers in the Midwest, one market manager conceded that recent shopper feedback about metrics was leading them to “take a much closer look at … not over-indexing on things like efficiency.”

Many shift, city and regional managers who spoke to The Times said they had protested the system internally for years. Several said they complained to higher-ups that rewarding or penalizing shoppers based on speed ignores the situations beyond their control. At least four shift leads, two of whom were at the company as recently as February 2020, said they tried to fight against firing shoppers who prioritized customer service over speed, often to no avail. Other former employees said the company was well-intentioned but, like many on-demand start-ups, it focused on growth in ways that put workers last.

Montalvo said the company “regularly reviews shopper achievement at each store to ensure expectations remain fair and attainable.”

Shoppers seeking protections have discussed unionizing — an effort the company is trying to discourage. Los Angeles shoppers received an email in August referring them to shopperfactsla.com, which makes the case against Instacart workers joining the United Food and Commercial Workers. UFCW in February successfully unionized a group of Instacart workers in Skokie, Ill., who are now negotiating their contract with the company.

A senior manager said at the Midwest town hall that shopper flexibility “is really at odds with some of the inflexibility and rules” often found in union contracts.

“We feel strongly that shoppers don’t need a union,” the manager said in response to a shopper who asked if the company is afraid they’re unionizing.

“I just encourage all of you to wait and see what happens at Skokie,” he said.

Instacart said it respects workers’ right to “explore unionization” but does not believe it’s in shoppers’ best interest. Montalvo said the company is bargaining with Skokie workers in good faith, but the final outcome “may be different than what the union had originally promised.”

Discussion of unionization comes as Instacart has laid off more than 200 in-store shoppers at 55 retailers across the country, including Aldi, Sprouts and Publix. The stores are now using Instacart’s platform and their own employees to handle curbside pickup orders.

Instacart said former in-store “shoppers have been hired at several retail partners.”

Even those with just weeks left on the job didn’t immediately escape Instacart’s metrics protocol. Five days after shoppers at one Sprouts location were given notice that they were being let go in a matter of weeks, their shift lead messaged them with the performance leader board.

“I like seeing those bad replacement numbers at 0%,” he told the soon-to-be-unemployed shoppers. “Let’s keep it up and don’t let out of stock items slow y’all down. Keep up on your messaging as well.”