Five times a day, tens of millions of phones buzz with notifications from an app called Muslim Pro, reminding users it’s time to pray. While Muslims in Los Angeles woke Thursday to a dawn notification that read, “Fajr at 5:17 AM,” users in Sri Lanka were minutes away from getting a ping telling them it was time for Isha, or the night prayer.

The app’s Qibla compass quickly orients devices toward the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia — which Muslims face when praying. When prayers are done, the in-app Quran lets users pick up reading exactly where they left off. A counter tallies the days of fasting during the holy month of Ramadan. Listings guide users to halal food in their area.

These features make it easier to practice the many daily rituals prescribed in Islam, turning Muslim Pro into the most popular Muslim app in the world, according to the app’s maker, Singapore-based BitsMedia.

But revelations about the app’s data collection and sales practices have left some users wondering if the convenience is worth the risk.

BitsMedia sells user location data to a broker called X Mode, which in turn sells that information to contractors. X Mode’s client list has included U.S. military contractors, the tech publication Motherboard first reported last week.

Mass calls to delete Muslim Pro and a separate Muslim matrimony app called Muslim Mingle have since echoed across social media, resonating among communities that have long been the target of government surveillance.

Majlis Ash-Shura, a leadership council that represents 90 New York state mosques, sent a notification urging people to delete Muslim Pro, citing “safety and data privacy.”

The Council on American-Islamic Relations, the nation’s largest Muslim civil liberties and advocacy group, sent letters to three U.S. House committee chairs asking them to investigate the U.S. military’s purchase of location and movement data of users of Muslim-oriented apps. CAIR called for legislation prohibiting government agencies from purchasing user data that would otherwise require a warrant.

In a statement, Muslim Pro denied that it sold user data directly to the U.S. military but confirmed that it had worked with X Mode. Muslim Pro said it always anonymized the user data it sold, and said that the company planned to terminate its relationship with X Mode and all other data brokers.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) said an investigation into the data broker industry showed that as of September, X Mode was “selling data collected from phones in the United States to U.S. military customers, via defense contractors.”

“Every single American has the right to practice their religion without being spied on,” Wyden tweeted. “I will continue to watchdog this announcement and ensure Americans’ constitutional rights are protected.”

X Mode did not respond to requests for comment, but reportedly ceased working with two specific defense contractors named in the Motherboard report. Muslim Pro did not respond to questions about whether executives were aware of what X Mode did with user information after its purchase.

Muslim Pro is trying to win back users worried about their privacy. Upon downloading the app, users now see a pop-up that says, “media reports are circulating that Muslim Pro has been selling personal data of its users to the US Military. This is INCORRECT and UNTRUE. Muslim Pro is committed to protecting and securing our users’ privacy. This is a matter we take very seriously.”

Screenshot of company statement in Muslim Pro app.

(Muslim Pro app)

Imam Omar Suleiman, a prominent Muslim scholar and the founder of Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research, felt the company’s statement was a deflection.

“There has to be some humility to accept their responsibility,” said Suleiman. “They should have said, ‘Look, we totally messed up. We should not have done that. We need to be more careful. And these are the steps that we’re going to take to remedy the situation.’ Instead, it seems like the response was just very defensive.”

BitsMedia was founded in 2009 by Erwan Mace — a Singapore-based iOS developer whose LinkedIn profile shows previous stints at major tech companies like Google, Akamai and Nokia-owned Alcatel. BitsMedia built and developed apps for corporate clients and an app-discovery service called Frenzapp, but Muslim Pro is far and away the company’s biggest success.

Mace told the site TechinAsia that he launched Muslim Pro in 2010 after noticing how his Muslim friends had to turn to the radio, the local mosque or the newspaper to find out what time to break their fast during Ramadan. By 2017, Muslim Pro had been downloaded 45 million times, piquing the interest of private equity firms Bintang Capital and CMIA Capital Partners. The firms acquired BitsMedia for an undisclosed amount and Mace left the company two years later.

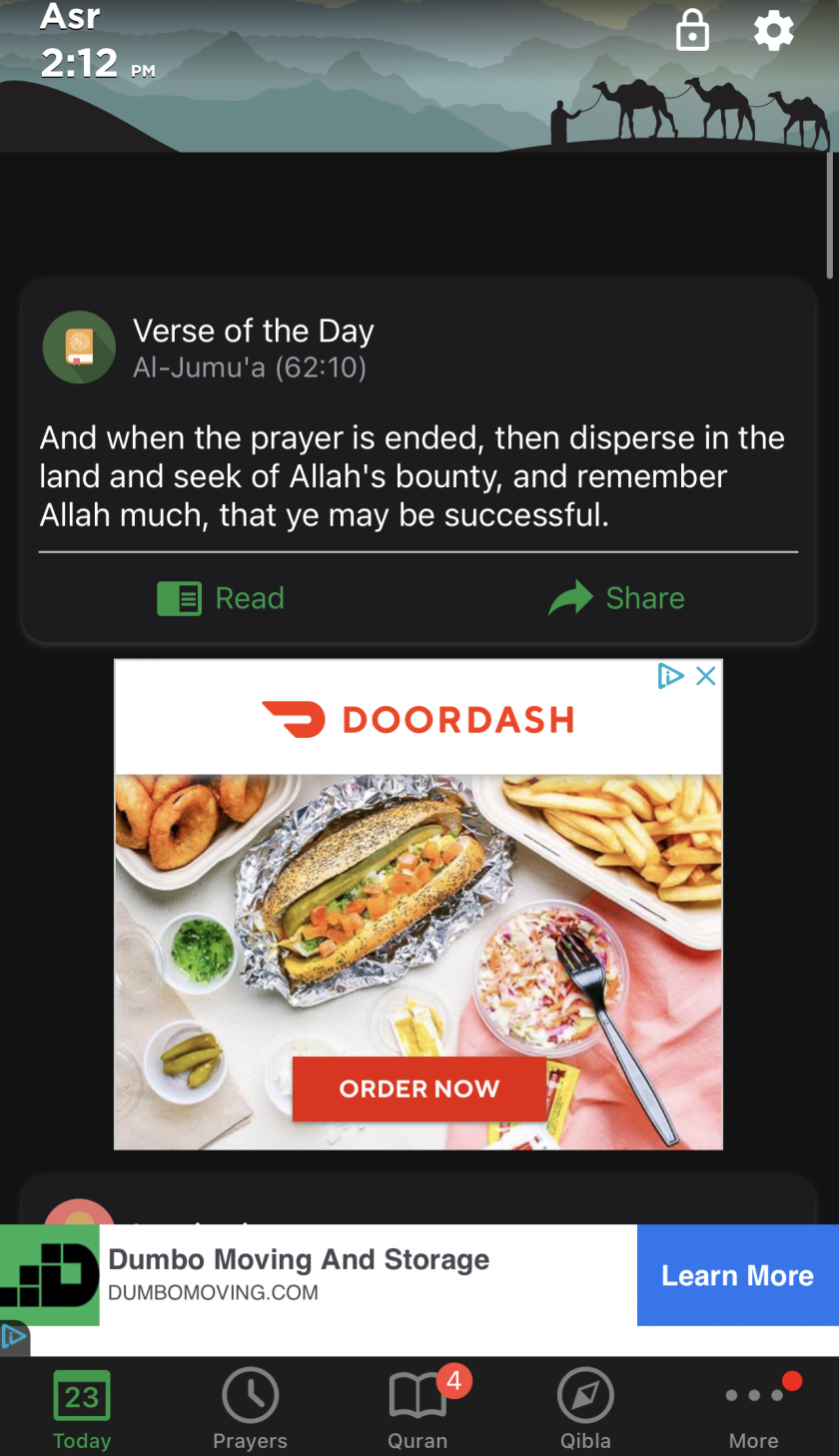

Muslim Pro offers two versions of its product: a free app that is supported by advertisements and a paid subscription service for those who prefer to avoid seeing pop-ups for businesses such as Doordash and Western Union under verses for the Quran. The company says the app has been downloaded more than 90 million times on iOS devices, and it has tallied more than 50 million downloads on Android devices, according to the Google Play store.

In the world of free apps and internet services, the sale and exchange of personal information are not unusual. In fact, in most cases it’s what keeps free apps free. Facebook, Google, Twitter and practically every other company sell ads against personal user information in order to help advertisers better target potential customers.

Screenshot of ads in the Muslim Pro app

(Screenshot of iOS Muslim Pro app.)

But for many Muslims, the sale of personal information by an app that helps them interact with their faith in the privacy of their own homes feels like a greater personal violation.

“This is not taking place in a vacuum,” Suleiman said. “This is part of a wrong pattern of crackdowns and all sorts of violations of our civil liberties that have preyed on our most basic functions as Muslims.”

Muslims in the United States and abroad have been the subject of mass government surveillance for years, at times, for simply practicing their faith or participating in faith-based activities.

The New York Police Department demographics unit — a counter-terrorism group launched in response to 9/11 — surveilled Muslims in and around the state to weed out radicalization based on indicators that the ACLU said were “so broad that it seems to treat with suspicion anyone who identifies as Muslim, harbors Islamic beliefs, or engages in Islamic religious practices.”

Muslim community leaders point to the expansion of the U.S. drone program under President Obama, which used drones for surveillance and targeted killings in Muslim-majority countries like Yemen, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iraq and resulted in hundreds of civilian deaths.

That’s why it’s so troubling that data showing how often Muslims engage with their faith and where they are could end up in the hands of the U.S. military, said Zahra Billoo, a civil rights attorney and executive director of CAIR’s San Francisco Bay Area chapter.

“This feels like a betrayal from within our own community,” said Billoo. “People feel that they should have been able to trust a company that markets and serves specifically the Muslim community — a community that has been under incredible attack domestically and abroad — to keep that data private, to be incredibly diligent about who they were selling it to, if they would sell it at all.”

While Muslim Pro’s data policies are broadly in line with the rest of the tech industry, the use of the app is an indicator of faith and religiosity in ways that few others are, Billoo said.

“Our religion cannot be assumed from some of the other software,” she continued. “But if I’m checking Fajr everyday on Muslim Pro, then that tells the U.S. military something specific about me.”

Billoo said CAIR is asking for a congressional inquiry — one that might get answers from the U.S. military about why the data were acquired and how they are being used.

In New York, where NYPD surveillance remains top of mind in the Muslim community, members of the Majlis Ash-Shura, the Muslim leadership council in New York, say the app scandal has inspired them to begin discussing lobbying for statewide consumer privacy legislation, akin to California’s Consumer Privacy Act. Members of the leadership council are no strangers to the idea of government surveillance — the group’s former president, Imam Talib Abdur Rashid, sued the NYPD for surveillance records on himself — but this is the first time it has considered steps to curb potential government surveillance through private businesses.

In the last week, many Muslims have sought out more alternatives to Muslim Pro, but given the importance of geography in calculating prayer times, it’s hard to find apps that won’t need to access location information. Islamic prayer times hinge on the position of the sun, with each prayer corresponding with different positions. It’s why prayer times change throughout the year as days get shorter or longer and vary from location to location.

Calculating prayer times requires inputting the longitude and date into a formula called the equation of time, which determines solar time, according to Omar Al-Ejel, a computer science major at the University of Michigan who built a prayer time app in 2015 that he continues to update. For example, solar noon — which is when the sun is at its highest point — is not always at 12 p.m. Knowing exactly what time solar noon is helps Muslims know when to pray Dhuhr prayer. (In Los Angeles on Monday, Dhuhr or solar noon is at 11:46 a.m.)

However, Al-Ejel said while the security of the data is not guaranteed, apps that do on-device calculations tend to be more trustworthy because location data aren’t automatically being sent to a remote server where it would be impossible to tell whether the data are being sold or misused.

Some Muslim Pro competitors have been releasing statements indicating they do not store or sell personal data. Athan Pro parent company Quanticapps said the company does on-device calculations and never stores or sells any personal data to any server — though its free version is ad supported. Another company called Batoul Apps — which provides a suite of paid and free apps, some of which are geared toward Muslims, without ads — also said it doesn’t collect or sell personal information. The company’s prayer time app is free.

We are proud to say that we don’t collect or give your personal information to anyone. Our apps have no ads and no analytics expressly so that no one will have access to any user information.

— Batoul Apps (@batoulapps) November 16, 2020

“When it comes to anything religious,” Al-Ejel said, “I feel like it should just be implied that you’re not selling any kind of information.”