Press play to listen to this article

BERLIN — American radio is a Berliner no more.

The postwar American presence on Berlin’s airways that began in the summer of 1945 when the city was still digging itself out of the rubble of World War II ended this month as the last U.S. radio station in the German capital ceased operation. For years, the station, known in its final iteration as KCRW Berlin, offered listeners a daily helping of local English-language news and eclectic music.

The idea behind the station was to deliver Berliners a dose of unfiltered Americana and to serve as a transatlantic bridge. Even in an era of podcasts, the offering found a loyal if small audience, from daily commuters to American expats.

“It’s a sad moment embodying the end of a tradition,” Anna Kuchenbecker, a member of KRCW Berlin’s board, said, blaming the shutdown on the pandemic. KCRW Berlin was operated in partnership with a California public radio affiliate with the same call sign. The economic fallout of the coronavirus forced the U.S. station to make steep cuts, including layoffs.

The closure comes at a time of deepening estrangement between the U.S. and Germany following years of Donald Trump’s attacks on Berlin. The longtime allies have recently been at odds across a range of issues, from climate policy and trade to foreign policy.

KCRW Berlin officials say that it would have been up to the U.S. to save the station because it wasn’t eligible to receive any of the billions in broadcast fees the German government collects in order to finance domestic public television and radio. But the U.S. government has effectively given up on its cultural outreach in Germany, focusing its efforts on other parts of the world instead.

“The pain that we are feeling with KCRW Berlin going away is something that is not necessarily felt in the U.S.,” the station’s program director Soraya Sarhaddi Nelson said.

But even in its home city, the station’s death received little attention; Berlin media barely took notice of KCRW’s shuttering or what it signified, noting the move only in passing.

End of an era

The tradition of U.S. radio in Germany began when the American Forces Network (AFN) went on air in the summer of 1945 from Berlin-Dahlem, a leafy suburb where U.S. forces were headquartered. The station’s mission was to keep the thousands of American troops stationed in the city informed and entertained, but its audience was much wider.

After Germany’s unconditional surrender to the allies in 1945, the country’s radio stations were first shut down and then reorganized with the aim of helping to “denazify” the country.

In a country that had been force-fed a steady diet of Hitler’s favorite brass-band marches and Wagner for more than a decade, AFN’s American sound — from George Gershwin to Billie Holiday — was new and titillating. That was especially true in the 1950s, when rock ‘n’ roll emerged as the West’s most powerful cultural weapon.

The old post-war AFN network was “probably the best foreign policy instrument the U.S. had ever thought of,” former U.S. Ambassador to Germany John Kornblum, who also helped start KCRW Berlin, told the station recently.

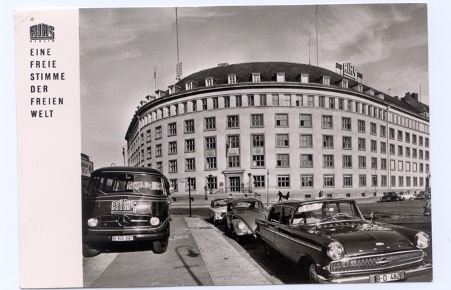

During the Cold War, the U.S. also operated German-language RIAS (Radio in the American Sector), which served as an antipode to the pro-Soviet radio programming in the East, calling itself “a free voice in a free world.”

After the Cold War ended and American troops left Berlin, AFN was eventually shuttered. RIAS’ radio operations were rolled into German public station Deutschlandradio, while its television arm went to Deutsche Welle, Germany’s state-funded international broadcaster.

But that wasn’t the end of American broadcasting in Berlin. AFN’s Berlin frequency was sold off to a rock station that carried Voice of America news broadcasts. Then, in the early 2000s, NPR — which serves as a national syndicator to over 1,000 radio stations in the U.S. — brought American public radio to the German capital.

Jeff Rosenberg, the founding father of NPR’s only self-managed station abroad, campaigned for years to get a frequency. “Tears were running down my face” when NPR Berlin went on air in 2006, he said.

The station enjoyed a loyal local following, both in Berlin’s burgeoning international community as well as among long-time Berliners. Still, NPR Berlin struggled to stay afloat. The “listener support” that sustains American NPR stations — voluntary financial donations collected during regular funding campaigns — is a foreign concept in Germany, where households pay nearly €20 per month for public broadcasting.

In 2017, Kornblum helped lure KCRW to take over from NPR. Ultimately, however, the American public station model proved unsustainable, especially during a crisis.

The snap announcement of KCRW’s closing prompted hundreds of listeners to contact the station, with many offering to help. But by then, it was already too late.

“I had no idea they had these problems,” said Charles Gertmenian, a Californian from Pasadena who has been living in Berlin for 20 years. “Now, I kick myself for not having organized a fundraising.”