Portugal

A stroll and a gourmet treat by the river at Amarante

My go-to place for escape is the mountains. In normal times, I’d make a beeline for the granite-strewn plateaux of Serra da Estrela or the wooded slopes of Gerês. But the ups and downs of lockdown have left me craving something a little less wild. I feel a need for repose, not action.

Amarante would be just the ticket. On the banks of the Tâmega River, a gorgeous bow-shaped bridge connecting its two halves, the town – north-east of Porto – is a maze of cobbled streets and quiet cafes that ask nothing of you other than to wander at will. I’d probably visit some of my favourite haunts: the medieval São Gonçalo church, the Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso art museum next door, the ruined Solar dos Magalhães manor house.

If my activity itch strikes, a stroll through the city park or a short bike ride along the old train line (now a cycle path) should scratch it.

As a very exceptional treat, I’d cap things off with a visit to Largo do Paço. In the Casa da Calçada hotel, a stately pile right on the river, it’s one of Portugal’s best restaurants outside Lisbon. Pooling my savings from a year of evenings in should see me good for a main course, at least. If my pennies stretch to a glass or two of vinho verde, all the better.

Oliver Balch

Italy

Restorative walking in the Dolomites

Fresh air, space and nature – these are the things I look for in a holiday, especially in these times. One place that offers all three in abundance is Renon (also called Ritten), a plateau that lies above the northern Italian city of Bolzano, or Bozen, in the Dolomites region of Alto Adige, known as South Tirol in English.

Sigmund Freud was Renon’s most famous visitor. During a three-month stay at Hotel Bemelmans-Post in Collalbo village in 1911, he wrote: “Here on the Ritten plateau it is divinely beautiful and comfortable … I have discovered in myself an inexhaustible desire to do nothing.”

Renon’s 300km of well-marked hiking trails, one named after Freud, are enough to keep you active by day and satisfyingly exhausted by night. My favourite goes up to Corno del Renon, a 2,260-metre summit with otherworldly views of the Dolomites and even a place to stay the night, at Corno del Renon mountain hut.

I head back to Gasthof Wiesenheim, a family-run guesthouse in Collalbo, which serves fantastic food. You don’t need a car to get to Renon – take a train to Bolzano and a cable car from there. On the plateau, a scenic light railway service connects the main villages.

Angela Giuffrida

Czech Republic

The delightful quirks of Kroměříž

Prague may be the Czech Republic’s spire-filled holy grail but it’s the country’s rural regions, with their madcap locals and tourist-free quirks, that give me a buzz. And nowhere embodies this quite like the town of Kroměříž, in south-eastern Moravia.

Constructed around the Archbishop’s Palace, a Unesco-protected baroque chateau, this old-world spot oozes tranquillity and warm-hearted Czech charm. In the palace gardens, peacocks strut within maze-like topiary, and a mini-zoo – replete with cockatoos, baboons and red-faced macaques – is an intriguing curiosity. For a bit of fun – especially if you have kids – take the electric train for a jaunty 30-minute ride (with English audio) around the grounds.

Nearby, the town’s dazzling cobbled square is full of terrific restaurants. The local brewery Černý Orel (the Black Eagle) is a particular favourite; a half-litre of its delicious semi-dark beer and a plate of traditional Czech svíčková (beef tenderloin in cream sauce) is my pub order of choice.

The Kroměříž attraction that gets me most giddy, though, is the outdoor lido. For the entry price of a pound, you can swim, drink beer, eat sausage and choose between two equally great sights: huge-stomached locals belly-flopping into the deep end or an unimpeded view of the gorgeous chateau.

Mark Pickering

Greece

Leaving the 21st century behind on Tinos

One of the best things about living in grubby, swarming, glorious Athens is that when the urban hustle gets too much, you can hop on a ferry and an hour or two later alight on a Greek island. There’s nothing like plunging into the Aegean to rinse off city life.

The restorative weekend rituals of striding across crinkly hills pricked with thyme, or idling in a kafenio and watching sunbeams flicker across limewash, have been agonisingly off-limits for much of the past year. So when lockdown lifts, I plan to take the slow boat to the Cyclades archipelago and Tinos, an island of luminous marble villages and profound, almost primeval beauty. At sea, Aeolus will blow away the internet signal, and I’ll stare at the widescreen horizon instead of the blurry blue light of constant connectivity.

There’s certainly no wifi at Krokos, an off-grid hideout way up in the misty, scarcely habitable mountains of Tinos. Camouflaged among spherical boulders like giant cannonballs, the two shacks – slabs of schist stacked by shepherds in a past age – seem to surface from the landscape. The cool, cave-like rooms are souped up with flea-market chic, while verandas dangle over rippling hills.

Krokos is in the centre of Tinos, so you can strike out in a different direction each day. Or you can recall how to stay still, feeling your senses sharpen as you tune in to the scratchy crickets and soulful owls, the drifting light and wind in the vines, carrying wafts of rosemary and verbena.

The owners, Sabrina and Jerome Binda, left Paris to pursue their passions on Tinos: she set up a ceramics studio and he launched a natural winery, Domaine de Kalathas. After a week or two at Krokos learning to throw pots, meandering about the vineyards, and acquiring a taste for their heritage grapes, I’m tempted to follow their lead and abandon city life altogether.

Rachel Howard

Norway

Lyngen’s dazzling skies and snowscapes

I was born in Longyearbyen, which claims to be the northernmost town in the world with a permanent population of more than 1,000. Even though I have travelled a bit and now live in Oslo, I still have a strong affinity with northern Norway, and the cold months in particular. While it’s not always a winter wonderland, squally days and nights have their magic too. There is something oddly soothing about storm-watching from the warm side of a window. Or driving with studded tyres in a slow convoy behind the snowplough with its flashing lights, while staying within two metres of the car in front so as not to lose sight of its tail lights through the storm. Most days are less dramatic though, if that’s possible in such a theatrical landscape.

I plan on heading to Lyngen, which is Norway in miniature – the imposing Lyngen Alps surrounded by two fjords, narrow valleys, dramatic waterfalls and colourful villages. It is roughly the size of the West Midlands, but with a population of only 2,800. And the people here are as warm as Scandinavians come – they even smile occasionally.

Then there are the northern lights – sometimes relatively calm, at other times frenziedly dancing across the sky … yet never making a sound. There isn’t a lot of noise around here: no hustle or bustle, no traffic, no nothing. And I love how the quiet nothingness is amplified by the pristine air. The temperature typically drops to minus 20C, and can even reach minus 40C, and that turns evenings around the wood burner in your log cabin into yet another highlight.

Gunnar Garfors

Netherlands

Cycling to carnival through the Limburg hills

People who don’t know the Netherlands often think of it as a country that all looks roughly the same: pretty little towns cobwebbed with canals, green fields freckled with windmills and dairy cows, and as flat as a pancake. The south-east of the country, however, isn’t like that at all, and that’s where I’m heading once lockdown is over.

The province of Limburg dangles like an untied shoelace from the bottom edge of the Netherlands. It is prettily forested and has the kind of hills that would go unnoticed in Britain, but by Dutch standards require crampons. Cycling through the trees, I’ll reach the Drielandenpunt (three countries point), where three nations meet on a hilltop – and where, with the borders open again, I’ll visit both Belgium and Germany just by taking a few steps in either direction.

After a slice of local vlaai (fruit pie) in a cafe, I’ll cycle on to Maastricht, which combines a grand Roman history and glorious old churches with a feisty local culture. If the vaccines come soon enough, I’ll time my visit to coincide with the annual carnival, when the city goes wild in a celebration that feels like a hybrid of Mardi Gras, Glastonbury and a raucous teenage disco. It’s always crowded, but I’ll relish being surrounded by others, as I dance, drink countless plastic cups of beer and eat enough rookworst hotdogs to give a cardiologist a heart attack.

Ben Coates

Switzerland

Relishing a burger on the slopes of St-Luc

I miss eating out. Restaurants were closed from early November to mid-December in Lausanne, where I live, and in many other parts of the country, including Valais where I often ski in winter. But with most Swiss ski resorts now open – and operating under strict guidelines – I’m hoping to head back to a mountain restaurant I discovered last year when skiing with friends in the small Valais station of St-Luc.

At the top of the Bella Tola lift, we basked in sunshine at 3,026 metres, ogling the jagged crown of peaks before us. Then we launched ourselves down a red run that promised a descent of 1,700 metres over 6km. My heart pumped hard, my cheeks stung in the chill and my smile felt as wide as the piste. Eventually, the slope narrowed and guided us to Le Prilet restaurant, where the scent of melting cheese beckoned us in.

We clattered through the door, peeling off layers before tucking into beer and burgers – fat, juicy and messy. Afterwards we lingered in the warmth, taking for granted the things Covid has since denied us: the company of friends, good food and the freedom of flying down a slope.

Caroline Bishop

Slovenia

Ljubljana’s heavenly food market

I’m lucky enough to live at the foot of the Kamnik-Savinja Alps, in a town called Kamnik, amid a landscape that could pass for the setting of The Sound of Music. This means I’ve been able to visit precipitous mountains, verdant cow-strewn plateaux and deep forests safely and freely, even during the tightest lockdown.

So while the city-bound may pine for wilderness, I am looking forward to a return to convivial, crowded social spaces. My first stop will be the central farmers’ market in Slovenia’s capital, Ljubljana. The market was designed by Jože Plečnik, Slovenia’s greatest architect, and completed in 1944 as part of Plečnik’s vision of creating a version of all the public spaces there would have been in an ancient Greek city, making Ljubljana into a new Athens.

The market is backed by a colonnade that leads on to the river and is an urban social centre. On Fridays, Odprta Kuhna (Open Kitchen) would normally take over part of the square and as many as 20,000 people would descend on a pop-up food fair with dozens of stalls selling everything from sauerkraut and Kranj sausage to šmorn (chopped pancakes topped with berry jam, a Habsburg favourite).

I’ll head to the stall with the longest queue and greet Marjetka, whose family are among the last in the world to produce Ljubljana cabbage, said to make the world’s best sauerkraut. Then I’ll stroll over for lunch at JB, which showcases the market’s produce in dishes I have dreamed about, like ravioli with chestnut, pear and foie gras.

Noah Charney

Austria

Swimming in the crystal waters of Lake Zell

I spent the spring and autumn lockdowns at home in Vienna, but the small window of domestic travel in the summer proved just how much I miss, and need, nature. I enjoyed days swimming in the huge bathing lakes of the Salzkammergut, and breathing alpine air in the mountainous region of Tirol.

On the way home, I drove past a stretch of Lake Zell, 50 miles south of Salzburg. The piercing blue basin is cradled by some of the highest mountains in Austria – a mix of glacier-topped, rugged peaks and softer, green alpine ridges.

The lake, a four-hour train ride west of Vienna, sits near the very centre of the country and is crystal clear because it is fed from mountain streams. I’m determined to return, and I’ll swim or rent a rowing boat from the lakeside esplanade and find a quiet spot in still waters far from the shores of the lake.

On another day, I’ll switch the altitude and head to one of the town’s four cable-car stations, with routes up the Schmittenhöhe. I’ll start with the gondola that gets me to the High-Altitude Promenade, a hiking trail at 1,939 metres that’s said to provide the best views of the lake below and the panorama of mountain summits.

Becki Enright

Wales

The return of rugby crowds

I was at Cardiff’s Principality Stadium the last time Wales played rugby in front of a full house. It was only in February but, flicking through the pictures and videos now, after everything that has happened, it feels a bit like I’m blowing away a thick film of dust from some childhood box of slides out of the attic, not simply thumbing left across my phone screen. There’s my wife’s cousin Hannah, her husband Huw, his brother and his wife, my wife and me, all grinning away in the stands, happily smashed on Brains bitter.

It’s only when something is taken from you that you realise just how much you miss it. I miss the slow walk from my old home in Canton to town more than the match itself. The buzz around the pubs, the bookies and the greasy spoons. How everyone wears a bit of red for luck, from the obvious (replica Wales tops, skintight and tugged down over beer bellies) to the oblique (the elderly homeless fella who’s tied a red ribbon round the neck of his beloved staffordshire bull terrier).

I miss how I’m always a bit late for the game by the time I’ve crossed the River Taff. I miss trying, and failing, to nip into a pub for just one last pint before kick-off. And I miss buying as much beer as I can carry from the stadium bars instead.

Then Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau, the Welsh national anthem, is being belted into the sky by tens of thousands of people and I forget everything. I forget I need to pee. I forget which drink was mine. I even forget I’m not actually Welsh.

Hopefully, it won’t be long before I can make that slow walk once more, but I’ll never take it all for granted, ever again.

Will Millard

France

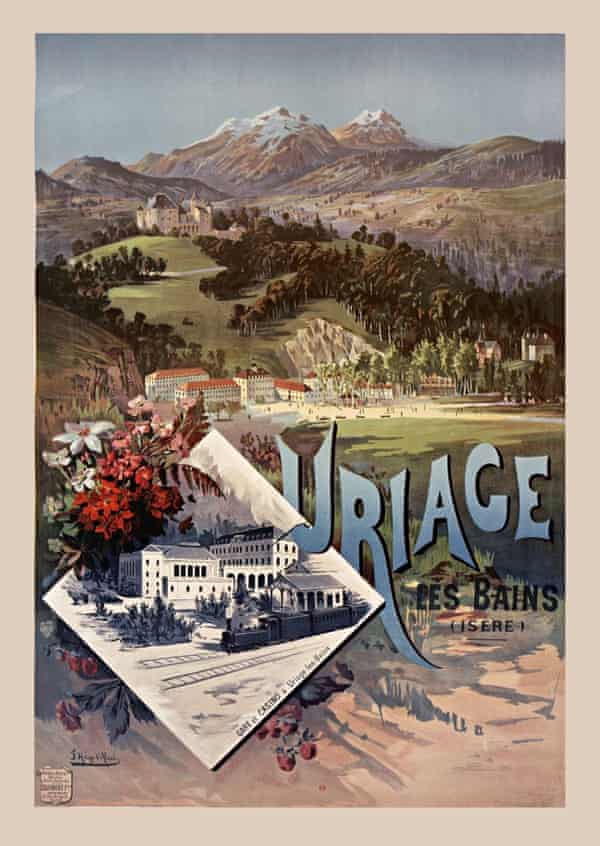

The curative waters in Uriage-les-Bains

Uriage-les-Bains, a genteel spa village 10km south-east of Grenoble, is a refuge of calm – and my ideal destination once travel restrictions are lifted.

Uriage’s water was officially declared “curative” in 1781, when a farmer noticed how healthy his animals were after they drank from the local source. His son built some wooden huts for those wanting restorative baths, and word spread; an elegant thermal resort was constructed in the 1870s, including a tramway to bring in wealthy patrons from Grenoble.

Little has changed since then, including the row of shops that occupies the old stables (from the days when spa guests arrived by horse-drawn carriage). There’s a baker, a grocer, a butcher, a couple of cafes and an ice-cream parlour, making it a picnicker’s paradise.

I dream of sitting under one of the Atlas cedars in Uriage’s giant park, watching dogs leap across the brook, and of walking through the pine-covered valley and perhaps joining the cyclists outside La Fondue for a dish of walnuts and a restorative glass of Chartreuse.

Behind the steamed-up windows of the village’s Établissement Thermal are swirling mineral-water pools, spray chambers and massage rooms. Outside, there are boules and tennis courts, a fairground carousel, belle époque villas and steep footpaths heading up towards the ski resorts of the surrounding Alps.

The thermal spas will reopen soon hopefully, followed by Uriage’s season of live soirées when the music wafts across the grass and over the willows and conifers to the turreted chateau perched above.

Jon Bryant

Northern Ireland

Getting to the heart of the nation

The first thing I am going to do is drive to the very centre of Ireland. From what I can tell it is a field. This is no great surprise. Most of Ireland, north and south, still is. It is either a few miles from the town of Athlone, in County Roscommon, or a couple from Loughanavally in neighbouring Westmeath. (The Hill of Tara, in Meath, also claims it. However, the Hill of Tara is as much the centre of Ireland as my house in east Belfast is.)

I think I drove past – or possibly even right in between – them back in September, when driving places was still a thing, although even then there was an announcement on the radio as I was crossing the border that people should only be making the journey for work. My work is writing books: I was travelling south to research the one I am currently writing. I sat in a layby weighing it up for 10 minutes then drove on. I wasn’t set on the centre then, but the Midlands more generally: the least visited part of the island. I think I had in mind to write at the end of my visit, “and now I know why”, but I had a lovely weekend in and around Westmeath and Offaly.

On the way home, I have an urge to go by way of Annaghone in County Tyrone – the geographical centre of Northern Ireland. (I’ve searched Google images. It looks a bit … field-y.)

In both locations I’ll be sure to stick to the western approaches. Then next time anyone asks me where I stand on Ireland, I can say without hesitation, “left of centre”.

Glenn Patterson

Germany

Experiencing the Lüneburg Heath’s wild beauty

Tourists to Germany often yearn for spectacular alpine panoramas or sublime Caspar David Friedrich vistas from the mountaintops. Not me. The landscape I long to rediscover is that of the north, which reveals its beauty in less dramatic fashion.

The Lüneburg Heath, a 107,000-hectare nature park in Lower Saxony, feels like it belongs in Scandinavia or a remote part of Scotland: the land is barren, with low-growing shrubs, wavy-hair grass and gnarly oaks clinging to sandy terrain.

For most of the year the nature reserve is windswept and rain-sodden, but from August to September the entire landscape turns purple as the heather blooms. Take a train from Hamburg to Handeloh, then a bus to Undeloh, where the heath starts just beyond the village pond. From here, keen walkers can embark on the 14km Heidschnuckenweg path to Niederhaverbeck, a hike named after the dishevelled local breed of moorland sheep.

Cyclists can explore the reserve by hiring bikes from Hotel Heiderose or Ferienhof Heins in Undeloh – or simply catch the horse-drawn carriage that leaves for the village of Wilsede (daily mid-May to end of September), and return in the afternoon for buckwheat gateau, the local delicacy served at Teestube Undeloh.

Philip Oltermann

Spain

I crave Madrid’s city life and art scene

I’ve spent lockdown up a mountain in Cádiz, so I’m yearning to be jostled in the dimly lit, deafening and cosy Bar Benteveo in Madrid’s Lavapiés district. My dream is empanadas (the owners are Argentinian), good beer and one of the retro armchairs by the window to watch people do normal things in a normal neighbourhood again.

I crave visceral city life: scruffy edginess, traffic, street art, creativity, designer-owned shops, neon, independent cafes, multicultural richness and stray cats winding between rickety pavement tables – and Lavapiés has it all. I have the perfect day planned: the gritty visual art centre Tabacalera to see a baffling but thought-provoking installation, then more esoteric stuff at La Casa Encendida gallery, followed by cake in the airy cafe. I’ll graze my way around the bars of Mercado de San Fernando, eating arancini perched on a stool at the Mercadillo Lisboa and pausing for wine at Bendito.

Ambling a bit further, I’ll rummage around antique stores and call into La Fugitiva, the creaky, quirky bookshop where customers can browse the well-curated selection of books with a drink in hand. It’s the polar opposite of online shopping, in the best possible way – in a barrio that’s the antidote to enforced distance and silence.

Sorrel Downer

Belgium

The bucolic charm of Flanders’ Westhoek

A weekend in the rolling hills between Ieper (Ypres), Poperinge and Ploegsteert feels like an escape to a part of Flanders that lives at a more relaxed pace. As the train from Brussels ventures deeper into the Westhoek region, each station feels like another marker away from the modern, urban heart of the country. Westhoek is still focused on agriculture, and roads appear to exist only to service the fields and the food they produce – meat, hops, vegetables and even wine.

The campsite at De Nachtegaal has vintage campervans and caravans for rent, and is on top of the 143-metre Rodeberg, which offers views south across the entire region. This is a landscape crisscrossed with walking and cycling trails, all navigable by numbered route posts (or knooppunten), which allow you to choose your own itinerary. They lead to first world war battlefields, through beautiful villages such as Kemmel (where you should visit Cafe Boutique), and to the Trappist abbey at Westvleteren, where you can buy beer brewed by monks.

Best of all, just 300 metres from the campsite is one of my favourite places to eat in Belgium. The Hellegat offers a warm welcome, simple, well-cooked local food (the ham hock in mustard sauce is sublime) and a wide selection of west Flemish beers made with local hops.

Philip Malcolm

Croatia

Gorging on “drunken meat” in Ilok

The eastern region of Slavonia is off-the-radar Croatia, and I’m planning to go as soon as we can travel. Specifically to Ilok, Croatia’s easternmost town, which is like a fairytale.

Ilok is surrounded by fortifications, including two monuments from Ottoman times and a medieval fortress rising above the Danube, but the main reason to visit is the 15th-century wine cellars. These supplied wine for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, and a bottle can cost £5,000. Happily you can taste it more affordably at the Festival of Traminca, which is usually in June.

You’ll also get to try the food, which has influences from Hungary, Austria and Serbia. There’s fish paprikash and something called pijana kotlovina, “drunken meat”, which is the speciality of a small winery north of Osijek called Vina Gerstmajer, where they cook meat in 10 litres of wine. You can prepare it with them and drink rakija (fruit brandy) while it’s cooking. It’s like being at a friend’s place – something we’ve all been missing in lockdown.

Zrinka Marinović

Ireland

Stargazing in west Cork’s Sky Garden

The elongated fingers of land that reach out into the Atlantic in Ireland’s remote south-west have come in for some dubious publicity of late. The success of the West Cork podcast, a compelling true-crime series about a brutal murder in the area, has lent a murky hue to the region’s ruggedly beautiful landscape. That focus is only likely to intensify in 2021 with the release of two documentaries about the unsolved case.

Those looking to experience a more uplifting side of West Cork should head first to the handsome market town of Skibbereen, with its striking steel-clad Uillinn arts centre and Saturday farmers’ market. Most destinations are an easy drive from Skibb: the pretty harbour town of Baltimore for ferry trips to the magnificent remove of Cape Clear, Ireland’s most southerly inhabited island; the spectacular Three Castle Head walk, and the long sweep of Barleycove beach and dunes at the western tip of Mizen Head; and, a little further afield, Dzogchen Beara, a Tibetan Buddhist retreat and meditation centre open to all and with some of West Cork’s most heavenly views.

For more secular enlightenment, book lunch, dinner or an overnight stay at the secluded Liss Ard estate just outside Skibbereen, which provides access to the Sky Garden. If you stand in this 50-metre by 25-metre crater – designed by the American artist James Turrell – and look up, the rim forms a visual ellipse that perfectly frames the sky. The sensory artwork is at once an immense naked-eye observatory, and a “celestial vault” that is peaceful, contemplative and supremely calming – a luminous tonic for our times.

Philip Watson

Poland

Łódź’s glorious rebirth … fingers crossed

Last year, an argument broke out within a group of my friends about the merits of the Polish city of Łódź (pronounced “woodge”).

In the 19th century Łódź was the beating heart of industrial Poland, a centre of the textiles industry, characterised by brutal working conditions and frontier capitalist excess. The city’s Jewish and German populations were either destroyed or driven out during the second world war (the Łódź ghetto was the second-largest in German-occupied Europe), while the city’s industrial base failed to survive the transition to capitalism after the collapse of communism in 1989.

Since then, it has gained a reputation as a city constantly on the verge of a glorious rebirth that has never quite arrived. But Łódź’s determined, continuing battle for recognition has yielded some museums dedicated to its fascinating industrial, wartime and cultural past – the city is the birthplace of pianist Arthur Rubinstein and has a world-famous film school that counts directors Andrzej Wajda and Krzysztof Kieślowski among its alumni. Many of its former industrial spaces are now bars, restaurants, galleries and independent shops.

Still, there are those who remain unconvinced – hence the disagreement among my friends. We had resolved to all meet in Łódź for a weekend to settle the argument, but life – and then Covid – got in the way. I have been dreaming ever since of a Łódź rendezvous that will serve as confirmation that this grim extended episode in our lives is finally over.

Christian Davies

Scotland

Discovering the secrets of Glen Lyon

During our months-long confinement, many of us have developed a keener appreciation of the world outside our walls. The great outdoors seems greater than ever. In Scotland, we’re lucky – we’ve got a lot of it.

I suspect that Scotland’s tourism industry will quickly recover, and as usual Edinburgh, Glasgow and the Highlands will prove popular in 2021. Fortunately, there are many roads less travelled. Take east Perthshire – I would.

Glen Lyon, along the Tay from Aberfeldy, is the glen of glens, with easy walks in the valley and several Munros surrounding it, and the Post Office Tea Room halfway in for refreshment and reflection. This is classic Scottish scenery as evocative as any in the Highlands or the Trossachs, but largely bypassed by tourists despite its accessibility.

There are great options nearby for eating and sleeping: the restored Grandtully Hotel, with the same owners as the estimable Ballintaggart Farm Cookery School up the road , is one of Scotland’s most convivial roadside inns, with a bar, bistro and eight rooms, all faultless in every meticulous detail. In Aberfeldy, the Watermill (cafe, gallery, home store and great bookshop), the Habitat Cafe and the Three Lemons bar/restaurant offer great grazing and browsing options.

There are countless easy walking prospects, including the celebrated beechwoods, the Birks of Aberfeldy and the remarkable Cluny House Gardens over the Tay, with its vast tree collection including rare redwoods and a thriving colony of red squirrels. Fuel your expedition with Glen Lyon Coffee from the company’s new laid-back roasting shed.

Pete Irvine

England

Trekking to find sanctuary on the Essex coast

In 2021, I plan to walk St Peter’s Way, a 40-mile, four-day trek across Essex. Pilgrims on this route have long relied on the hospitality and kindness of strangers, but in 2020, with many pubs and hotels closed, finding a room at the inn proved impossible.

I hope to begin my walk at the Church of St Andrew in Greensted, the oldest wooden church in the world. Later the trail passes Mundon’s forest of “petrified” oaks, whose water-starved arms reach for the sky like a coven of witches surrendering before Matthew Hopkins, the Witchfinder General who once interrogated some of the unfortunate villagers of these parts.

Essex has long been a county of political dissent and utopian dreams. In the late 19th century, the village of Purleigh was the headquarters of an anarchist community, who grew grapes and denounced currency before infighting led to members hopping on their bicycles and pedalling away to better things. The off-grid community of Othona, founded in 1946 near Bradwell-on-Sea, proved more successful and still welcomes those looking for respite.

The walk ends at the remote chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall. Built from the ruins of a Roman fort by Saint Cedd in AD 625, this is a place to find sanctuary, as well as to shelter from the salt-marsh winds.

Essex, with its wide skies, is the perfect place to blow away the cobwebs of last year and follow in the footsteps of countless others who have journeyed here to give thanks for safe passage through difficult times.

Carol Donaldson

Denmark

Descending into CopenHell

I first attended CopenHell in 2011. It was a small, obscure festival for hardcore heavy metal fans, and 8,000 of us gathered at Refshaleøen, a former shipyard on an artificial island where a large mural of a wolf stared down at us. Heavy metal is not featured at many festivals, so there was a collective feeling of “Look what they made for us!”

Many of the crowd looked like they might tear off my arm and have it for breakfast, but I have never attended a festival where everyone was so happy: the Hell-goers queued politely for beer and gallantly let me stand in front of them if they were blocking my view. Some even brought their children – the sight of a grinning toddler wearing a tiny Slayer T-shirt and ear defenders really warms your heart.

Since then CopenHell has grown into one of the largest festivals in Denmark, and I’ve been back every summer. There was no festival in 2020 for obvious reasons, but I can’t wait to go back and let my hair down in a drunken crowd. I might even give the heavy metal karaoke a go.

Andrea Bak