The temperature stood at 42C as I rode into Salamanca one dog-day afternoon a little over a year ago. After two and a half brutal days I had finally completed stage one of the 1941 Vuelta a España, a stage won in just under eight hours by the man who would go on to claim victory in the first edition of this national bike race held under the Franco regime.

Julián Berrendero and his fellow racers were cheered through the hot streets by 40,000 spectators at the end of a stage that had begun in Madrid with the riders dutifully raising their arms in the fascist salute while singing Cara al Sol (Face to the Sun), the Falangist anthem. Berrendero would have known the words well: he’d just spent 18 months in Franco’s concentration camps, where prisoners had to belt it out twice a day, any shortfall in enthusiasm or lyrical slip-up earning them a beating.

It was a challenge to picture that thronging scene as I wobbled to a sweaty halt on Avenida de Mirat, the stage one finish line. Spain had just emerged from a national lockdown that was among the most rigidly enforced in Europe, and the grand sandstone plazas were sparsely dotted with masked citizens. It would be some time before I encountered a fellow foreign visitor.

In the weeks ahead I was routinely the sole guest at hostels and hotels along the route, greeted by mixed emotions (on masked faces) whenever I wheeled my filthy bike up to the reception desk: thank you, Lord, for delivering us a paying customer in this time of crisis, but could we have a cleaner one next time?

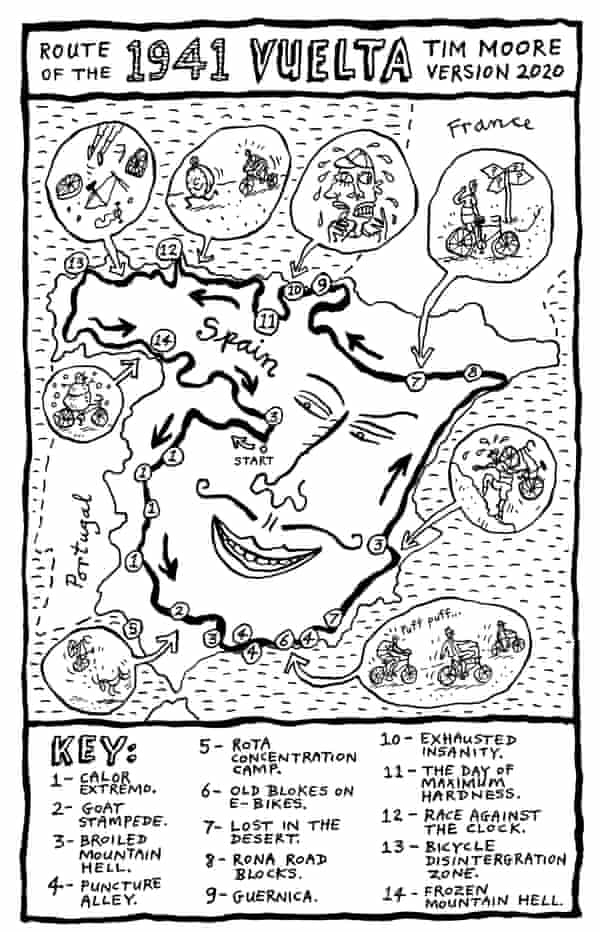

In a fleeting gap between waves of pandemic, I had managed to slip out of Britain and into Spain, sneaking in a cheeky 2,760-mile retracing of the longest bicycle race in that nation’s history.

If I hadn’t had Covid myself a few months earlier, I’d never have set off, out of concern for getting it or spreading it. Yet though it was five years since I’d cycled further than to the shops and back, I completely failed to factor in my own physical unreadiness for this undertaking. Indeed I secretly entertained a theory that my brush with Covid might prove beneficial, in a kind of what-doesn’t-kill-you-makes-you-stronger fashion. “The doctors aren’t quite sure how to explain it, but at 56, Moore is riding like a man half his age.”

It seemed a bit rude that I wasn’t granted a single day to sustain this fantasy before it was put to the sword. At the first hill I came to I suffered appalling cramp and had to push the bike up. On my first evening, I fell foul of Spain’s nocturnal dining habits and lapsed into an unsightly coma after ingesting three beers on an empty stomach while waiting for the bar’s kitchen to open. It didn’t help that my bike – a 1970s racer – was geared for a professional.

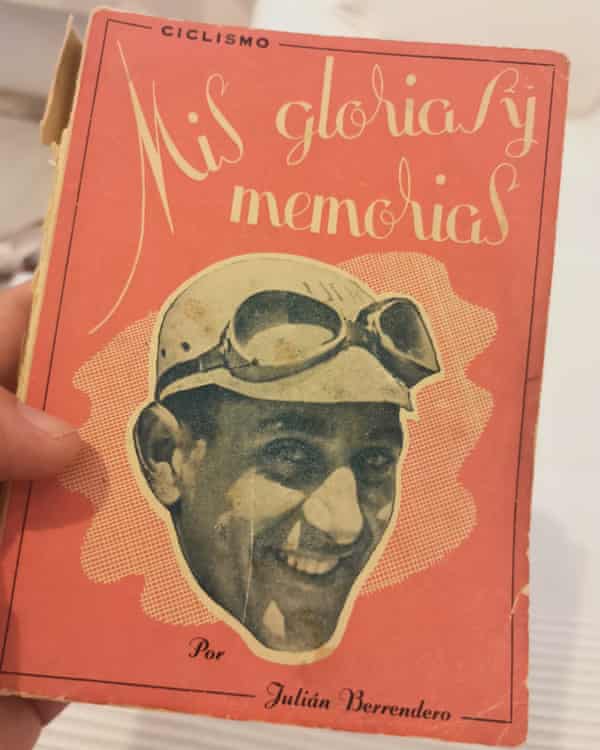

My fascination with Berrendero’s story took root while I was locked down in London and ploughed through a history of the Vuelta that had been in my bedside pile of unread cycling literature. The Spanish civil war erupted during the 1936 Tour de France, in which the man I came to call JB made his name by winning the King of the Mountains competition. At mid-race press conferences, JB and his Spanish teammates – anti-Francoists to a man – issued defiant statements of republican solidarity. But when he returned from France in 1939, Berrendero was arrested. As Spain’s best-known sportsman, he had to be made an example of.

Franco’s sporting administrators pitched the 1941 Vuelta as “the tour of a nation reborn”, a bid to stitch back together the country they had just ripped in half. But it didn’t take me long to suspect that the chosen route was more about rubbing the losers’ noses in it. JB’s fate was sealed in Salamanca, where the Nazis who did so much to ensure the nationalist victory had curated a vast archive of political information on Franco’s behalf. An information request I sent to the Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica in Salamanca procured a scan of a wonkily typewritten record card with my man’s name at the top. In three dozen words, JB’s crime was spelled out: a pledge to donate half his winnings to republican war orphans, as reported in the Communist daily, Workers’ World.

From Salamanca, for several hundred miles riders followed the route that Franco’s Column of Death had marched in 1936, slaughtering villagers as they went. After hitting the Mediterranean at Málaga, the race tracked the road along which 3,000 refugees died, shelled from the sea and strafed from the air, with barefoot, elderly stragglers machine-gunned by Italian troops lent to the Falangist cause by Mussolini. Later on there was a conspicuous detour through Guernica in the Basque country, scene of the civil war’s defining tragedy, articulated by Picasso’s famous black and white painting.

Yet in the hundreds of contemporary race reports I read, all vetted by Franco’s censors, there wasn’t a single mention of the war that had reduced half the towns the riders passed through to blood-stained rubble. Nor was there more than oblique reference to the desperate shortages that made it almost impossible to source the 7,000 calories required to ride a bike all day – after sleeping at Cáceres, a Game of Thrones city rising from the leathery plains of Extremadura, the racers were sent on their way without any breakfast. This was an era when cats and dogs were a rare sight in Spain – they’d all either died of starvation or gone into the casserole.

Though my head kept telling me it was all a long time ago, my heart was in a different time zone. When you’re retracing the Spanish civil war, 1941 doesn’t seem like ancient history: the ageless towns and vast, broiled landscapes of Extremadura brought the past into hauntingly close focus. At pretty little Zafra I stared at bullet holes in the cemetery walls, legacy of yet another Column of Death massacre, in a town whose priest would boast of killing 100 “reds” – burying one woman alive and shooting dead a man he found hiding in his church’s confession box.

At the end of each day’s ride I would try to tackle a painful disconnect: enjoying the colonnaded, palm-lined squares filled with promenaders while trying to square the dreadful things their grandparents had done to each other with the placid, genial citizens around me.

Despite the climatic disincentives and my feeble old legs, every morning I couldn’t wait to get back out on that sticky, deserted tarmac. When London lockdown got too much for me, going out for a ride felt like a break for freedom, a glorious release from all the oppressive, dystopian weirdness. It seemed even more oppressive in Spain, and so much sadder: all those dutiful mask-wearers forced to restrain their hardwired native impulse to gather and hug. What a towering relief to hit the open road and leave all that behind, to carry on as if the whole world hadn’t spun out of control, as if riding a really old bike for hours and hours in an open-air oven was mundane rather than completely nuts.

From Málaga I tracked the ghost-town costas all the way up the east coast to Barcelona, through forests of package-tour hotel towers, their dusty glass doors now padlocked. Halfway up, where the 1941 route had swerved inland after Almería, I contrived to get lost in the Tabernas desert, where many spaghetti westerns were filmed. In those dune-like ochre hills, the sun-baked solitude turned up way past 11, I did battle with all of cycling’s cruellest deceptions: the false flat, the false summit, the false cafe-bar with its false help-yourself Coke fridge out front.

Spain is one of Europe’s most mountainous countries, but its topographical variety fully asserted itself only when I laboured over a hilltop in Rioja and beheld the fearsome green and grey peaks that define Biscay and the Basque country. What a contrast there was between the orderly, sun-soaked ranks of vines and sunflowers I had just left behind and the wild, jagged vertical mess that now glared down from under leaden clouds.

Like most Spanish cyclists, Berrendero mastered his trade in these big wet hills, and I didn’t want to let him down. Except I did, and almost at once. After ingesting a can of energy drink the size of a tennis-ball tube, I began to oscillate horribly, superhuman up one hill, subhuman up the next, my heart dancing to some very strange rhythms. I’m not surprised the manufacturers swerve some of the lairier side-effects in their advertising, but any properly responsible commercial for an enormous container of carbonated stimulant really should incorporate a clear warning: “CAUTION: organs may burst clean out of chest. If affected do not operate bicycle.”

In truth, JB would prove a rather chequered inspiration. He never spoke of his 18-month ordeal in the camps. Fearful of further punishment, he euphemised the experience as “the period when I lost my racing licence”. Instead he processed the resentment into race fuel, running on pure hatred. Against the authorities who had stolen his sporting prime – he was 29 when he was released – and against the fellow professionals who had escaped the same fate.

I had nailed my colours to the mast of an embittered loner who regularly came to blows with his teammates, and refused to share his winnings with them in defiance of the sport’s most fundamental etiquette. In his final interview, just a few weeks before his death in 1995, JB was asked who he wished to thank for their support in his career. “Do me a favour and print this in large letters,” he told the journalist. “Nobody.”

Covid’s second wave began to break after I hit Spain’s top-left corner, at Vigo in Galicia. From here onwards, on my return to Madrid, the disincentives for long-distance cycling steadily multiplied: local lockdowns, police roadblocks, receptionists aiming temperature guns at my sweaty red forehead.

Fearful that my mission might be undone at the death, I recklessly attempted the entire last stage of the 1941 Vuelta in a single go: 225km from Valladolid to Madrid, with the race’s tallest mountain in between. I’d only ever ridden further in a day once before, and that was 20 years earlier.

At 8pm, with the sun setting behind me, I lethargically pursued my 15-metre shadow towards Madrid’s glinting glass towers. All those hours before, hammering out of Valladolid, it had felt as if the heroic import of my mission must be screamingly apparent, as if I was exuding a sparkly glow that would compel motorists to afford me a wide and respectful berth and salute in awe as I shot past. Now I felt invisible, hollowed out and worn to nothing. My eyes registered scenes half-remembered from my ride out of the capital six weeks before. Franco’s scabby victory arch, sickly yellow in the dying light, passed by in a dim blur.

What, in all honesty, would JB have thought of my ride? I would have loved to look him in his bright blue eyes and say: “I did it, Don Julián. I bloody well did it.” He might have been impressed. He might have been flattered. He might have laughed in my face. Anyway, I had excelled myself. That’s all you can hope for.