On March 2, the nation’s annual Read Across America Day (a holiday once synonymous with Dr. Seuss, designated on this date to honor his birthday), Dr. Seuss Enterprises released an unexpected statement. The venerable author’s estate announced that it has decided to end publication and licensure of six books by Theodor Seuss Geisel, including his first book under his celebrated pen name, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (published in 1937), and If I Ran the Zoo (published in 1950). “These books portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong,” the statement read, alluding to their appalling racial and ethnic stereotypes.

The estate’s decision prompted days of relentless cable news coverage from Fox News, as well as cries about “cancel culture” from prominent conservatives, including House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, who accused Democrats of “outlawing Dr. Seuss” on the House floor. Sales of Seuss’ most-beloved books skyrocketed amid the discourse, topping Amazon and Barnes and Noble’s online bestseller charts throughout the week. Meanwhile, copies of the now-discounted books soared in price, with resellers listing those titles for up to $500 on eBay.

Dr. Philip Nel, a distinguished professor of children’s literature at Kansas State University and the author of Was The Cat in the Hat Black?, tells Esquire that this conversation about racism and prejudice in Seuss’ books has been underway for decades. Even during the author’s lifetime, Nel reports, Seuss was roundly criticized for racial and gender stereotypes in his books, yet he was also the author of actively anti-racist narratives, like Horton Hears a Who and The Sneetches. Nel spoke with Esquire by phone to explain how we should understand this ongoing conversation about updating and curating Seuss’ legacy, as well as how we should talk to children about books that contain racist content.

Esquire: Could you share a few examples of the racist words and racist imagery found in these discontinued books?

Philip Nel: The most egregious ones come in If I Ran the Zoo, from 1950, which includes a page featuring the mountains of Zomba-ma-Tant, with helpers who all wear their eyes at a slant. In this book, Gerald McGrew was collecting animals from around the world for his zoo. These are caricatures of Asian people who are helping him gather the animals. The same book has the African island of Yerka, where Gerald McGrew will bring up a tizzle-topped-tufted Mazurka, an imaginary Seuss bird. It’s being carried by two caricatures of African men who, in addition to the usual racist caricature, also have tufts on their heads, which accentuate their resemblance to the bird. If you miss the animality and the caricature itself, Seuss has got a little extra touch to tie them to the bird.

One of the themes across Seuss’ work is the use of exotic, national, racial, and ethnic others as sources of humor. I don’t think he meant that with malice, but to use someone’s nationality or race as a punchline doesn’t land well, especially if you are a person of that nationality or race. I don’t think he thought about how that might be hurtful to the people who identify themselves in that way. I think it’s important for people to understand that a lot of Seuss’ racism here is operating unconsciously. It’s something he learned from being steeped in a very racist American culture, which remains true of American culture today, although in different ways.

In And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, published in 1937, we see a man who eats with sticks; he is colored yellow. He has a triangular, conical hat, a long pig tail, and of course, slanted eyes. In 1978, in response to criticism, Seuss revised that drawing. He removed the color yellow and took off the pig tail. It’s still a stereotype—just a less egregious one. In describing that change, he would say things like, “I removed the color and the pigtail. Now he looks like an Irishman,” which is supposed to be a joke, but it also diminishes the importance of that change, and the seriousness of making the change. The basic themes of caricature across these six books are people of African descent, Asian descent, Middle Eastern descent, and Indigenous people.

ESQ: How do the events of this week fit into the context of the broader conversation about Dr. Seuss’s work and legacy? Is this the first time that Dr. Seuss Enterprises has taken such an active hand in updating the author’s body of work and rejecting some of his views?

PN: Yes, it is. They have certainly let works go out of print and come back into print before. They have re-published Seuss books under a different pseudonym. He also used the pseudonym Theo LeSieg, for example. His real name was Theodore Seuss Geisel; LeSieg is Geisel backwards. He wrote 13 books under that name, so they’ve published those under Dr. Seuss, the more famous name. But they have never, until now, done what is essentially a product recall, where they’ve said, “We’re not going to publish these six books anymore. We’re essentially taking responsibility for the culture we put out into the world. Profiting off of books with racist imagery is not something we want to do.”

I don’t know if there’s a profound ethical revelation they’ve had, where they’ve suddenly realized, “We need to be committed to social justice.” I don’t know if it’s a brand issue. Maybe they realized racism is bad for the brand, and so to sustain the brand, they need to address it. Whatever the motivations are, it’s a good decision, but it is the first. It’s the first where they’rethoma essentially saying that the product is defective, and they’re not going to manufacture it anymore.

ESQ: Does this decision have precedent with other authors of children’s literature? I’m reminded of when the estate of Hergé pulled books like Tintin in the Congo.

PN: It absolutely has precedent. Dr. Dolittle, for example. You can get a bowdlerized edition of it, which is to say, an edition that’s been cleaned up. That term comes from Thomas Bowdler, who produced issues of Shakespeare that were suitable for the family. He cleaned up Shakespeare’s language, so the term to “bowdlerize” is to clean up a work by removing the “offensive bits.”

It’s a solution with problems, but it’s been a strategy that people have taken, both the estates of authors and authors themselves. Roald Dahl changed Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which in 1964 had Oompa Loompas who were African Pygmies. From the 1973 edition forward, they are now white and from Loompa Land. It’s still Africa, but it’s not named as such. They are still an entire race of people who are glad to be shipped in crates to a factory where they live and work, and are paid literally in beans. It doesn’t actually erase the slavery colonialist narrative of the book. It makes it less obvious, given that they’re no longer Black, but it doesn’t change the fundamental assumptions of the book. In situations like this, the edits usually don’t work. The offensive bits are coded into the structure of the story.

ESQ: You touched on Seuss altering a character in his first book. Were there other occasions of him being called to respond to criticism during his lifetime?

PN: There were, and he was hugely resistant to it. There was one change that he made willingly; it was to The Lorax. There was a couplet about Lake Erie in there. It was “someplace that isn’t so smeary,” I think, and then a line like, “Things are pretty bad enough at Lake Erie.” The people who cleaned up Lake Erie contacted him and said, “Hey, could you take this line out?” He did it willingly.

The change to And To Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street was something he did begrudgingly. Critiques of gender in his works—he dismissed those out of hand. In Mulberry Street, there’s the line, “Say, even Jane could think of that.” Why does it have to be a girl who has the inferior imagination? He just mocked that criticism.

There’s a New York Review of Books essay by Alison Lurie that fairly called Seuss out for having almost entirely male protagonists. Any female characters tend to be the antagonists. They tend to be presented unsympathetically, even if they are the protagonists. Seuss responded to that by saying, “Tell her that most of my characters are animals, and if she can identify their gender, I’ll remember her in my will.” As in the previous response, he delivered it as a punchline. That’s how he interacted with his critics and with the world more generally. But it’s also dismissive—he didn’t take her valid criticism seriously.

Sally doesn’t speak at all in The Cat in the Hat. She says absolutely nothing. It’s a little boy who does the speaking in that book. Lurie had a good point, but as usual, Seuss was snarky and resistant to altering his work.

ESQ: The decision that Dr. Seuss Enterprises made has been explosive. You have Fox News running three consecutive days of coverage, and other conservative voices treating this as an example of cancel culture. Why has this become such a political flashpoint?

PN: Those are bad faith actors. Those are not people who are willing to have a serious conversation about race or racism in children’s media. For them, it’s a really useful point of distraction. We’re in a pandemic, we have an economic crisis, and the party they’ve aligned themselves with doesn’t really have anything to say about that, except that they would very much like to continue redistributing wealth to the wealthy, because that will trickle down and save us all. This is a really great way for them to pull in an audience and find an imaginary target for everyone’s legitimate frustration.

People are angry and upset for real reasons. Cancel culture is not actually the cause of their problems, but this offers a way of deflecting that into a problem created by liberals and people of color. Racism is the Fox and Republican brand. It works for them because, with children’s books, you have something for which people feel incredibly nostalgic. These are works that you grow up reading. You incorporate them into yourself as you’re still very much figuring out who you are, what you believe, and what you love. When someone is critical of something that you fell in love with as a child, it can feel as if they’re being critical of you.

Fox could take that and say, “Let’s reflect on that. Why would we feel attacked if someone was critical of a childhood favorite?” Instead, they say, “Let’s amplify the anger here, and make it about the critique rather than listen to the critique.” It’s a really effective ploy, but it’s dangerous and disingenuous. If you can find something like that and run with it, as they’ve done for days, then you’ve got a solid marketing strategy for this cancel culture hysteria you’ve decided will be good for your brand.

ESQ: What do you make of the fact that secondhand copies of these books immediately skyrocketed in price, following the announcement? There was a copy of On Beyond Zebra going for $1,500 yesterday.

PN: Unless that’s a signed first edition, I wish them luck. There are so many of these books in print that the imagined scarcity the marketplace seems to be creating is truly imaginary. I imagine some opportunists will manage to make a buck off of this. But if you want a decent used copy of one of these books, they’re not scarce.

ESQ: That’s part of what’s so tiresome about equating these books falling out of print to banning the books. The books aren’t going anywhere; no one’s burning them.

PN: Exactly. No one’s setting these on fire. No one’s saying you cannot read them. No one’s saying they must be removed from libraries. No one’s saying they must be removed from your home. True censorship would be exactly that. As my friend, the scholar Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, has pointed out, “Curation is not cancellation.” Nothing at all is canceled. But I would say to people who find the framing of cancellation useful: what sort of culture are you defending? What is it that you’re afraid will disappear? Are there cultures we might want to cancel? Say rape culture, or say white supremacist culture. Are these cultures that you think we should support? If so, why is that? They frame it as a “they’re coming for you” argument, not really saying why there might be some underlying issues in a culture that people would want to change.

ESQ: How do you reconcile the tension between Seuss speaking out against racism in some of his political cartoons and in actively anti-racist books, like Horton Hears a Who or The Sneetches, but at the same time, recycling these racist caricatures in his other books?

PN: Racism is not an “either or,” as most people think it is. It’s a “both and.” You can both try to oppose racism and not be aware of the ways in which your own beliefs and visual imagination are shaped by that same racism. That’s the case for Seuss. He did speak out against racism; for example, he wrote an essay on humor in 1952, in which he specifically criticized racist jokes. During the Second World War, he did cartoons that were explicitly critical of Jim Crow laws. At the same time, those World War II cartoons have grotesque caricatures of Japanese Americans and of the Japanese.

I think it’s important to understand that if you’re a steeped in a racist culture, as you are if you live in America or pretty much anywhere in the world, that’s going to influence the way you see the world. It will influence you in ways you’re not aware of. It will influence you without your consent. That’s why we need to take the question seriously, because if you don’t reflect, then you continue to carry forth these ideas—perhaps unintentionally, perhaps unwittingly, perhaps against your own stated principles and beliefs. I think that’s what Seuss did, but I also think that’s true of a lot of us. I would indict myself there, as a white guy writing about racism in children’s books. I sometimes call Seuss “the white guy who isn’t as woke as he thinks he is.” But I would also level that at myself, because white supremacy has a way of making itself invisible to its benefactors. I am one of its benefactors, and I will always be one of its benefactors, even if I don’t consent to that. Even if I say “I do not want a benefit from white supremacy,” I benefit from it, because my entire country is structured to serve those interests, and it has been since its founding.

Racism is not an aberrant part of American life. Racism is not a bug; it’s a feature. It’s woven throughout our culture, including culture that you love, and that’s upsetting. Let’s work through that and think about why it’s upsetting. Let’s think about what Seuss we might want to keep reading, and what Seuss we don’t want to keep reading, or what Seuss we should read in a very different way. That’s a healthy conversation to have.

ESQ: Let’s say you’re a parent and you own copies of these books, or you’re a teacher and they’re in your classroom. How do you open that conversation with a child?

PN: First, you need books that offer positive examples. You need books to tell the truth. You need books that do not caricature people. It’s important that all children see truth. Whether it’s seeing themselves represented with respect, or whether it’s understanding that they as white kids are not the center of the universe, or understanding that all groups of people are worthy of respect. That’s a baseline.

Once you have that context, if you want to do this sort of work, you can have what is going to be an uncomfortable conversation. It has to be an uncomfortable conversation, because those are the only kinds of conversations about race and racism that are meaningful. Be uncomfortable; acknowledge that you’re uncomfortable. Talk about what character is. What does it mean to reduce someone to a set of features that mock them and make them funny? What does it mean to mock someone by exaggerating something about them? This is not something you want to enter into lightly. If you take this approach, some sort of anti-racist education might be helpful for a teacher wanting to pursue this, because you’re going to need to be prepared for a lot of difficult questions.

But on the other hand, if you don’t have these uncomfortable conversations, then people don’t learn. Say that it’s okay to be angry at a book. It’s okay to criticize a book, and to recognize that a classic author maybe shouldn’t be quite so revered. If you are a child of color seeing yourself ridiculed in a book, it’s really important for you to know that you can be angry at that book. You can argue with that book.

For white children, you can’t deny the fact that they too are impacted by race. They can unknowingly perpetuate racism. Children as young as two years old know what race they are, what power it confers upon them, or what powers are denied to them because of that. When adults say, “Children don’t think about this,” the reality is that children may not be able to articulate it, but they do understand. There is a place for these conversations in classrooms. It’s not, “We’re going to do this in an hour this afternoon.” It’s part of your curriculum. Anti-racist education is vital and necessary and difficult, so prepare yourself when you do it.

ESQ: Turning our lens away from nostalgic books to contemporary children’s literature—to your mind, is it becoming more inclusive? What areas of improvement remain?

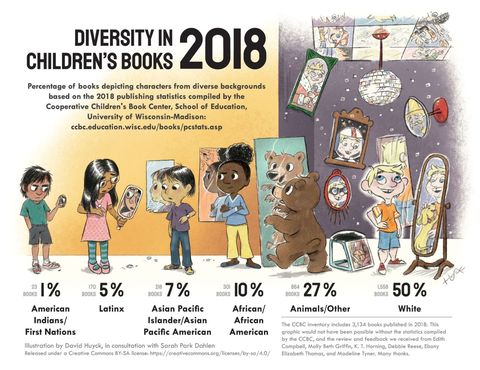

PN: It’s becoming more inclusive, but we still have a long way to go. There’s still a huge gap between the over 50% of school-aged children who are non-white and the number of books produced each year featuring non-white characters. Something like 25% feature non-white characters, and that’s a huge improvement, but only around half of those were actually written by non-white authors.

This is part of a long struggle. This is not new. The modern movement against racist children’s books might be said to begin in the mid-sixties. It goes back further, though—there’s a Brownies book co-edited by W.E.B DuBois, featuring such writers as Langston Hughes, published over a century ago. That particular publication was a monthly magazine dedicated to “children of the sun.” It was to offer them a vision of themselves as fully human, which was not really available yet. The history goes even further back to anti-slavery literature, which was read by Black children.

ESQ: If one good thing comes of this news cycle, I hope it’s that people who are not paying attention to the inadequacies of children’s literature are awoken to what’s happening.

PN: I hope so too. We have to be hopeful, because that’s what allows us to act in the world. If you can view the world and see possibility, then you can change the world. That doesn’t mean being naive, or denying the extraordinary challenges, but it does mean saying, “What can I do?” When you take action, you produce hope in yourself. Taking action is itself a producer of hope. Now more than ever, we really need that.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io