Each time I played through the interactive narrative of “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’” I was struck by how the game tensely toed the line between optimism for the future — infused with adoration of our loved ones — and just plain exhaustion at everything, a nagging emotion that can simmer below our daily interactions.

It’s present in our dearest relationships. It’s there in casual ones. And it rears its head even in those that are strictly transactional.

Arriving as the rare game to celebrate Ramadan, as well as one that aims to explore the subtlety of our closest partnerships, “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin,’” due April 14 for PCs and Macs, might surprise you.

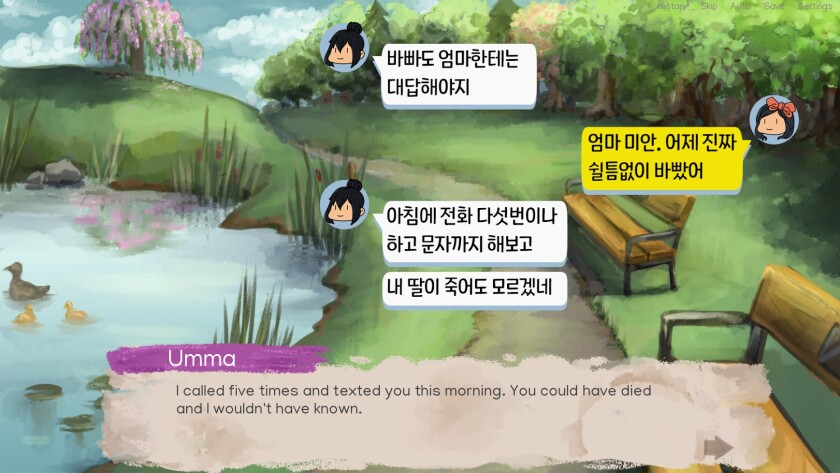

The game drops players into a bright world in which we direct conversations and then leaves us with thoughtful questions to ponder personal boundaries with others — as well as whether we’re fully respecting our own. Like last year’s short and revealing “We Should Talk,” a game about a relationship teetering between serious commitment and two people just giving up, “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’” shows how easy — and tragic — it can be to miscommunicate, even when people have the best of intentions.

“A lot of people with unhealthy boundaries treat everyone the same,” says game designer Alanna Linayre, speaking of the therapeutic inspiration behind her work.

How to navigate relationships, from the personal to the transactional, is a key component of “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’.”

(Team Toadhouse)

Games tend to do ‘renegade’ or ‘angel.’ Real life doesn’t work that way.

Alanna Linayre, game designer

“They give the same trust to everyone,” she continues. “They spill their life story. Then their friendship is tested. There are numerous ways to get hurt: The other person drops the ball, or is mean, or isn’t supportive. Then the person who shared their life story feels betrayed. But the person on the receiving end never asked or earned that. People need to earn the right to hear your story. They didn’t earn your inner peace, and you freely gave it.”

So how does that fit into a game?

Linayre wants to erase the idea of making the so-called right or wrong choice in a game, exploring dialogue that rewards players for being healthy, even if it goes against their natural game-playing instinct to take what is clearly implied as the positive action. These instincts are often what gets rewarded in story-driven games.

But in “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’” we see a friendship on the verge of being torn apart by self-doubt and misdirected anger. We make the choice, for instance, to simply give someone space as we balance one friend’s frustration and another’s spiral into depression as she fears her life’s work — a food truck food court — slipping away.

“Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’” asks players to steer the conversations of best friends turned business partners Amira and Jessica. By setting the game around a religious period such as Ramadan, the game can quickly shift between intimate and communal conversations. We are tasked with questioning when it’s safe, more or less, to be unguarded, and since Amira’s food is her art, there are plenty of fragile emotions to play with.

“Games tend to do ‘renegade’ or ‘angel,” says Linayre. “Real life doesn’t work that way. Games can be so useful in role-playing and playing pretend and testing out something you wouldn’t do in real life. In a game, you can try again. Maybe we can push people to be more brave in this game, or in our next game be more like their inner person, or we can push people to keep things to themselves. It’s about showing a role model in the safe space of a game.”

“Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’” is one vignette of a larger video game project from Team Toadhouse, which is using games to explore the challenges of forging connections in adulthood. At certain points, the game reflects the personal thoughts and concerns of its designer, as Linayre’s fictional work taps her real-life experiences — and her therapy sessions — as inspiration.

“Good Lookin’ Home Cookin,’” which is a complete hour or two of story with a beginning, middle and end, will eventually figure into a broader game titled “Call Me Cera,” which is still in development. Linayre says that at times “Call Me Cera” will mirror her own journey. Now 32, she spent her 20s in New York focusing on acting and then relocated to Austin, Texas, where games became her focus.

“Like Cera, I wanted a fresh start,” Linayre says. “I moved to Austin, I started therapy and I got a new job. I learned healthy boundaries. That completely changed my life, and I wanted to share what I learned about it with as many people as I possibly could.”

But communicating, even vicariously through the interactive space, also provided lessons, especially in how personal Linayre could get without overwhelming a player. The designer is frank in conversation and strives to be equally transparent with her game development, documenting in detail the development of “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin,’” including everything from the cost of art to hiring cultural consultants (current total for the whole game: about $10,000).

“Good Lookin Home Cookin” is a celebration of Ramadan and the culture that surrounds the religious holiday.

(Team Toadhouse)

When Muslims are in video games, they’re usually the enemy or someone to shoot at. They’re never portrayed in a joyous light. But there is real joy, and a lot of things that have to do with food.

Alanna Linayre, game designer

“At first, Cera was going to be very much like me — have bipolar disorder and PTSD, but I found that was too much,” Linayre says. The artist gets the bulk of her funds as a self-care consultant for independent game studios but has also been paying pandemic-era bills by waiting tables.

“It was alienating,” says Linayre of going deep on mental health in her games. “Everyone can relate to starting over. Everyone can relate to having anxiety. Everyone can relate to not being great at making friends. But not everyone can relate to a manic episode.”

She cites the Australian sitcom “Please Like Me” as well as the work of the late actress/author Carrie Fisher as the rare pieces of pop art to accurately capture mental health and living with bipolar disorder, which she has shown to friends and romantic partners when words have failed her. She wants her games to fulfill the same role — to tackle mental health without being about mental health.

“I was able to sit down and watch this entertaining show with my partner and point to things and say, ‘See that. That’s a manic episode,’” Linayre says. “Being able to point to yourself in media — or have a friend play a game that has a person like you in it — it helps you understand yourself better, it helps your friends and family understand you better, and it helps you communicate things that you’re not able to articulate.”

Here, Team Toadhouse is using the visual novel framework to deal with a number of sensitive topics, including those surrounding race and religion. And yet “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’” isn’t about, for instance, the racism faced by its lead characters of Amira and Jessica, but it’s most definitely present, and will no doubt be on the mind of any player hip to current events and the drastic rise in Asian hate crimes.

We see how one teen, meaning ultimately no offense, practically jumps in fear when presented with South Asian cuisine. And we see how the protagonists are on guard in nearly every conversation, wanting desperately to share their culture and food truck dining spot with the world but also hesitant to trust their own vulnerability.

Linayre cites a talk given at the Game Developers Conference in 2018 by Osama Dorias on Muslim representation in games as one that inspired and challenged her. But it also made her feel obligated to portray characters and experiences that weren’t just her own.

“My personal opinion on this is that most writers/developers/creatives share similar life experiences,” says Dorias. “A big benefit of tapping into representing experiences that are not their own is that their work would stand out from the crowd. I believe that devs who do this properly and respectfully will also grow as people. Seeing things from other points of view has that effect on people.”

For “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’,” Linayre worked with more than a dozen cultural consultants, some her friends and some she hired, and also ran questions by Dorias.

“When Muslims are in video games, they’re usually the enemy or someone to shoot at,” Linayre says. “They’re never portrayed in a joyous light, and I worked in a Hasidic Jewish center for two years, and it’s the same. Religions that aren’t a white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant, Christmas thing don’t get portrayed in a joyous light in our media. They’re somber and cultish. But I learned in the Hasidic center that there is real joy and a lot of things that have to do with food.

“When I started to create this world and these characters, it made sense to do it during Ramadan,” she continues. “I was thinking of Osama’s GDC talk and I messaged him and … he told me all about the restaurant culture. Then I was like, ‘That’s it. That’s the game.’”

Part of it, at least.

When the eventual “Call Me Cera” is complete, “Good Lookin’ Home Cookin’” will fit into an ambitious storyline about, basically, learning how to read a room. The characters of Jessica and Amir will resurface, but we’ll see them from a different perspective. Those who play both games will be equipped with more background knowledge that can inform a player when it’s safe to test or respect a boundary or to understand why someone is retreating without taking personal offense.

“For the vignettes that go with ‘Call Me Cera,’ I try to make it so you have to choose the healthy option,” Linayre says. “So if you come on strong to a person who is at work — they’re being friendly because they’re at work — or they don’t have interest in being your friend, it doesn’t matter how badly you want to be friends. If you come on too strong, that negatively affects Cera’s relationship with that character and you won’t be able to become friends with them later in the game.”

If that sounds harsh when it’s written out, Linayre stresses that is not the case, especially for those attempting to navigate the finicky and fragile world of grown-up relationships.

“It’s about bravery,” Linayre says, “and reaching out when you need help, and recognizing where others are at outside of your own feelings.”