No moment in literature has affected me like the moment eight-year-old Lucy Pevensie pushes through that wardrobe into Narnia. It showed me that one of the most essential ingredients of childhood is curiosity: Lucy may be the youngest and frequently overlooked but it is she who notices the wardrobe and in doing so finds her way through to a magical kingdom.

Childhood is full of doorways, most of them unseen, and at eight years old, you are starting to understand that the world is big and varied and full of wonder, and provided you don’t get side-tracked into growing up too soon, the possibilities are infinite. I remember a doorway from my own childhood, and I often wonder whether the reason I believed so wholeheartedly in Narnia was because the landscape beyond the blue door in the wilds of Scotland was every bit as magical.

I grew up near a village called Edzell, between Aberdeen and Dundee in Angus. Weekends were spent camping up the glen, scrambling over the moors and jumping into icy rivers. But of all the wild places I explored, there is one that sticks out. After you leave Edzell, you pass through a wood and a few fields before crossing an old stone bridge and there, on your left, is a little blue door in a stone wall.

You could miss it if you didn’t know it was there but my parents knew about it and pushed it open. What lay beyond could well have been Narnia. On one side, thundering through a steep gorge, was the North Esk River, browned by peat from the moors, and on the other, a little path wove through rhododendrons, silver birches, beech trees and a long-forgotten folly. The gorge opens up eventually, then the moors take over, leading all the way to Loch Lee and the cave where the sixth Earl of Balnamoon (a Jacobite who returned from Culloden with a price on his head) hid for over a year.

As a child, I watched salmon leap from the brilliantly named fishing pools beyond the blue door (Kitbog, Witch’s, Badger) and played hide-and-seek inside Doulie Tower (a folly built around 1780, when Lord Adam Gordon, commander-in-chief of the army in Scotland, acquired the estate and turned it from “the wildest state of barrenness” into woods filled with Scots pines, oaks, rowans and silver birches). I watched dippers gliding through the Rocks of Solitude (a picturesque narrow stretch of the North Esk) and I listened to my father’s stories about trolls who lived beneath the gnarled roots of beech trees. It felt impossible that all this should exist on the other side of that little blue door, yet it did.

Sometimes, when you return to a childhood haunt, the landscape looks smaller and less enthralling. Not so with the blue door: whenever I step over the threshold I feel the magic stir: river spray hangs in the air; beech leaves glow; the moss is a creeping fairytale carpet. And when I started my Unmapped Chronicles series, I thought about the thrill of stepping through the blue door and about how it makes me feel, every single time.

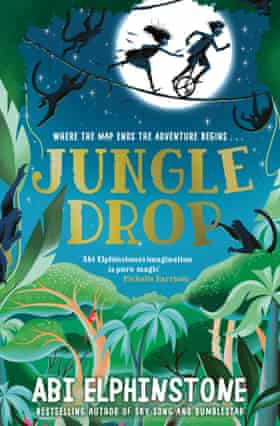

Each book in The Unmapped Chronicles follows a child who finds a doorway to a secret land whose fantastical creatures conjure weather for our world. In Rumblestar, Casper Tock opens a grandfather clock and discovers a sky kingdom ruled by wizards with unending pockets. In Jungle Drop, twins Fox and Fibber Petty-Squabble squeeze through a closing train door and are whisked to a glow-in-the-dark rainforest complete with gobblequick trees and golden panthers.

As we approach this strained new year, I want children who read The Unmapped Chronicles to feel there is still wonder, joy and hope out there. Because as Casper says in Rumblestar: “That’s the thing about locked doors: you never quite know what’s on the other side …”

Jungle Drop (Simon & Schuster) is out now. A new edition of Everdark is released on 7 January. The Unmapped Chronicles books are on sale at the Guardian Bookshop from £6.99