The world of sports never stops jumping and running, shooting and hitting, winning and losing. Occasionally, this chaos of constant action brings a moment that lingers forever, like the taste of perfect filet mignon.

The most memorable involve competitive struggles that carry tinges of social significance: Billie Jean King versus Bobby Riggs, the Dodgers versus the Astros’ drummer, Lance Armstrong versus the truth.

One such moment was March 8, 1971, 50 years ago today.

Into a boxing ring in Madison Square Garden stepped two men who had never lost a fight, had no intention of losing one that night, and who had story lines that played into the anger and divisions of a time of war in Vietnam and a Richard Nixon presidency.

Muhammad Ali, 31-0, would fight Joe Frazier, 26-0. It was a time when boxing mattered, when it often shoved aside the likes of pro football and pro basketball for prime space on newspaper sports pages. The minute the two signed on to do battle, it became the Fight of the Century. The hyperbole was justified, the label accepted to this day.

Ali was the star, as much for what he had done outside the ring as in it. He won an Olympic gold medal in Rome in 1960, bounced off the top rung of the victory podium and never stopped moving, or talking. He changed his name from Cassius Clay, told the world that “I float like a butterfly and sting like a bee,” and won his first two pro fights before that Olympic year ended. When he beat the feared Sonny Liston twice a few years later, the sports world stood up and took notice.

Then, in 1967, when called to step forward to serve as a soldier in the Vietnam War, he refused. His draft status had been changed from 1-Y (not fit for military duty for failure of written tests) to 1-A (the first group drafted).

When Ali got the news of his draft status change, he was training for a fight in Miami. Local broadcaster Bob Halloran, who went on to become a casino executive in Las Vegas, rushed to Ali’s house to confirm and get a scoop. He made sure to disable all the phones in the house to keep the scoop for himself (no cell phones in those days) and was the first to hear Ali say, “I got no quarrel with them Viet Cong.”

Joe Frazier poses by a poster advertising his “victory party” as he leaves his dressing room after a final public workout in Philadelphia ahead of his title fight against Muhammad Ali in 1971.

(Bill Ingraham / Associated Press)

Frazier was the son, and 12th child, of a one-armed South Carolina sharecropper. He worked the fields with his family, once breaking his left arm chasing a 300-pound pig. According to a book written by Jerry Izenberg, “Once There Were Giants, the Golden Age of Heavyweight Boxing,” that’s where Frazier acquired his huge left hook. There were no medical facilities to treat the fracture, so Frazier worked hard to strengthen it as it healed on its own.

He left South Carolina after seeing the beating of a fellow worker by a plantation owner and knowing that being a witness put him in danger. He ended up in Philadelphia, a city full of boxing gyms.

Frazier won the next Olympic gold, taking the Olympic title in Tokyo in 1964. He broke his thumb in the semifinal, told nobody and won the final mostly one-handed. As a pro, he was the original “Rocky,” working in butcher shops, punching meat carcasses and running up long steps. Sylvester Stallone portrayed that, Frazier actually did it.

Frazier also turned pro quickly and won his first 10 fights by knockout.

Their paths met on that Monday night, 50 years ago, with Ali staring across the ring in his bright red shorts and Frazier staring back in his strangely less-than-macho paisley green. It is sometimes lost in all the memories and story lines about the fight that Frazier won a 15-round decision and knocked down Ali in the 15th round.

Muhammad Ali vs. Joe Frazier in the ‘Fight of the Century’ on March 8, 1971, at Madison Square Garden in New York.

Among Bob Arum’s most searing recollections of that night was heading to Madison Square Garden, while hearing from friends scrambling for tickets to the closed-circuit telecast.

Those were the days when movie theaters, along with the live gate, provided the fight revenue. This was before pay-per-view on your home TV, before satellite hookups, before the internet. The big fights were at your local movie theater and you paid your $5. It was always Monday nights because that’s when the theaters did their least movie business.

Arum was a young Harvard law school grad who made his mark as the lead tax lawyer in the government’s prestigious Southern District of New York. Once, at the behest of Bobby Kennedy, then U.S. Attorney General, Arum stopped a tax fraud attempt by New York lawyer Roy Cohn, who was promoting a major fight and trying to pay his boxers out of the country to avoid taxes. Cohn was the adviser to Sen. Joe McCarthy during the controversial Congressional hearings on communism in the 1950s and was also a lead lawyer and confidant for a young Donald Trump.

Arum had become a boxing promoter, almost out of happenstance, through his friendship with former NFL star Jim Brown. That eventually led to a partnership with the Black Muslims, where Arum became Ali’s attorney and fight promoter. Starting in 1966, Arum would promote 16 Ali fights in the next 12 years, including several outside the country when Ali was banned in the U.S.

On March 8, 1971, the fight was not Arum’s promotion.

“I heard this guy Jerry Perenchio was offering $5 million to the fighters,” Arum says, “and I laughed. It was a joke. I thought he was just some Hollywood clown. I penciled it out. It couldn’t be done. Judge [Roy] Hofheinz in Houston — we had done some fights together — called and said he could come up with the money. I told him not to worry. This wouldn’t work.”

“It was racism in a sports environment. I call it sneaky vitriol. People choosing sides. To whites, Frazier was the good (Black man). Ali was the favorite of younger people, the more liberal ones.”

Tim Ryan, radio broadcaster for the “Fight of the Century”

Arum knew you couldn’t cover $2.5 million per fighter, plus promotional expenses, at $5 a ticket, or even $10.

“It wasn’t even close,” he says.

What Arum never figured was that Perenchio, and his money partner, Lakers owner Jack Kent Cooke, would charge $25 a ticket. And get it!

“I knew they’d made it when I watched all my friends scrambling for theater tickets that day,” Arum says. “That really got Perenchio started. He and Cooke made about $11 million off the fight. I think Perenchio died a billionaire.”

Arum attended as Ali’s lawyer. What he saw that night, he says, remains the “biggest sporting event in my lifetime. Nothing else even comes close.”

He saw a crowd of celebrities, much more than usual for a big fight. People had clear rooting agendas. The older white people were for Frazier, the younger people and most Black people for Ali. To the Frazier backers, their fighter was a hard worker who did his job and kept his mouth shut, while Ali was a draft dodger and a loudmouth, anti-war extremist. To the Ali fans, Frazier was an Uncle Tom, an image Ali had planted and would regret later in life. The crowd represented racism, anger, irrationality and even hate.

“People say today that the electoral is so politicized,” Arum says. “I’m not sure it wasn’t worse then.”

When Ali lost the decision, Arum was in shock.

“I scored him losing the fight,” he says, “but in my heart, I thought he would never lose.”

The play-by-play announcer

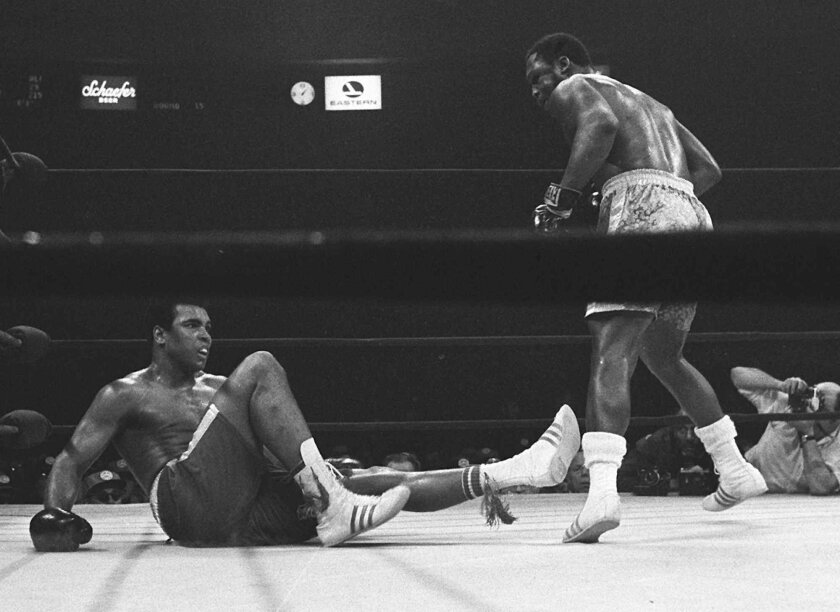

Muhammad Ali looks up toward Joe Frazier after getting knocked down during their 1971 title fight at Madison Square Garden in New York.

(Associated Press)

By 1971, Tim Ryan had advanced past the fuzzy-faced, new-kid reporter phase. But that didn’t make the phone call he got the week before the Fight of the Century any less stunning. He was asked to do a radio play-by-play of Ali-Frazier.

Ryan was 31 then, had lots of hockey experience and was working both as a TV sportscaster at WPIX in New York and broadcaster for the Rangers. His boxing experience had been limited to occasional fights on Mutual Radio.

“I was stunned to get the job,” Ryan says. “It was just dumb luck.”

Perenchio and Cooke had decided to protect their close-circuit telecasts however possible. One way was to shut out radio. If you couldn’t hear the fight anywhere, you were more likely to buy a theater ticket. At the last minute, New Zealand asked for a broadcast. But there wasn’t an English speaking telecast they could hook into, so the promoters gave in on one for New Zealand and Ryan got the phone call.

Then, just days before the fight, it was discovered that Armed Forces Radio had no broadcast. It had been traditional that soldiers abroad would get broadcasts of major fights. Perenchio and Cooke had missed that nuance and said no. When the potential controversy started to be understood, the idea was floated that Armed Forces Radio could piggyback onto the only English broadcast going out — to New Zealand.

“I was asked if that was OK,” Ryan says, “and I was thrilled. I got a call from some general, thanking me and saying he was sorry they couldn’t pay me. I didn’t care.”

Ryan’s impressions of that night remain vivid, and similar to Arum’s.

Joe gets down on his knees in front of the kid, looks him right in the eye and says, ‘You tell your dad that Ali was drugged, that I drugged him with three left hooks.’ ”

Jerry Izenberg, reporter recalling an interaction Joe Frazier had with kid after the fight

“You could feel it, the palpable tension,” he says. “It was racism in a sports environment. I call it sneaky vitriol. People choosing sides. To whites, Frazier was the good [Black man]. Ali was the favorite of younger people, the more liberal ones. People pick sides when they go to fights, but this was different.”

Ryan says he took the Frazier decision as a correct one. He also says it took him a while to understand what he had been part of.

“Eventually, I realized,” he says, “that this will be something I will talk about for the rest of my life.”

Ryan’s broadcast turned out to be the standard for this fight. The closed circuit, estimated to have gone to 300 million people worldwide, was done by veteran Don Dunphy and analyst Archie Moore. But Perenchio had also hired for the broadcast his friend, movie star Burt Lancaster, who ruined things by never shutting up.

The sportswriter

Joe Frazier, left, puts Muhammad Ali on the ropes during the fourth round of their heavyweight title fight in New York on March 8, 1971.

(Associated Press)

Izenberg is 90 years old. He just cut a new deal to keep writing for the Newark Star-Ledger. He has probably attended and written about more boxing matches than any other living journalist. He interviewed Ali and Frazier more often, ate with them more, wrote about them more and had better access than all others. His aforementioned book is more memory than research.

On the night of March 8, 1971, Izenberg wasn’t at Madison Square Garden.

“My father-in-law died the night before,” he says.

A few days after the fight, he watched a tape, agreed with the decision, and started to follow up. He pursued new angles, did what a gumshoe newspaper reporter does, what he still does now.

“I knew that Ali was going on TV,” Izenberg says. “I thought I better get to Frazier in Philly. I go there. I walk into his gym. First thing I see is a floor-to-ceiling picture of Joe looking at Ali, who is on the canvas after the 15th round knockdown.

“I tell him we need to talk. He says we’ll go to a deli, get some food, then talk.

“At the deli, three kids come running up to Joe. One says his daddy told him Ali lost the fight because he was drugged. Joe gets down on his knees in front of the kid, looks him right in the eye and says, ‘You tell your dad that Ali was drugged, that I drugged him with three left hooks.’ ”

For Izenberg, what happened next remains his best summary of Ali-Frazier — the men, the fights, the glory and the tragedy.

“The kids leave, Joe looks at me and says, ‘What do I have to do to convince people I won; what do I have to do to get out of his shadow?’”

From that, Izenberg — whose chapter about Frazier in his book is titled “The Man Who Wasn’t Ali” — concludes, “He never did.”

The aftermatch

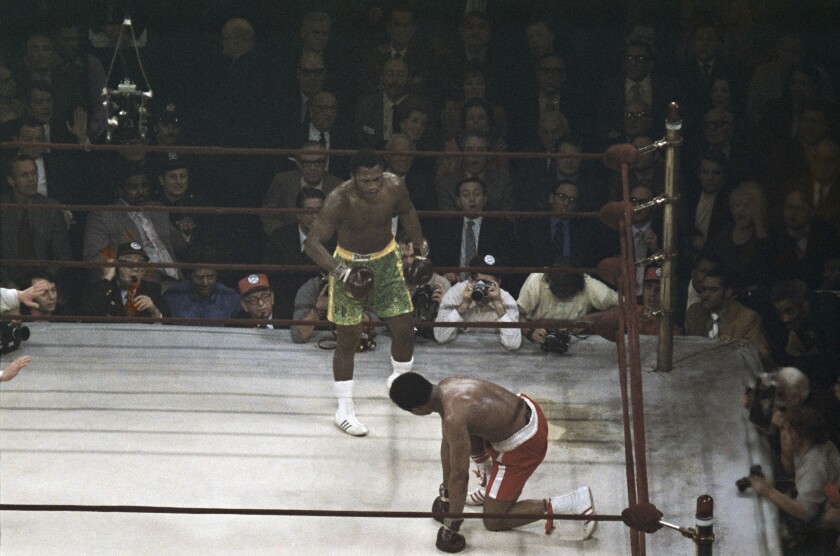

Joe Frazier stands over Muhammad Ali in the 15th round of their boxing match at Madison Square Garden in New York on March 8, 1971.

(Associated Press)

When the Fight of the Century ended, Diana Ross — one of the dozens of celebrities brought along by Perenchio — went to see Ali in the locker room to commiserate. When she knelt down next to him, Perenchio walked by and Ali whispered, “Take a look at the guy who paid me $2.5 million to get whupped.”

At ringside, Dunphy, who had broadcast more than 2,000 fights, didn’t do the signoff. Lancaster just kept talking until broadcast time ran out.

Arum, always looking for new angles, had cut a deal with 7-foot-1 basketball star Wilt Chamberlain to fight Ali for the heavyweight title. When Ali lost to Frazier, there was no title to fight for, but Arum pushed on. If Wilt signed the contract, he would still have a compelling event (a freak show). He convinced Wilt to bring his agent to Hofheinz’s office in Houston for the signing, but was aware that Wilt was getting cold feet. Arum instructed Ali to not say a word, to not spook Wilt. But when Wilt had to duck his head just to get in the office door. Ali couldn’t resist.

“Timber,” he yelled.

Wilt and his agent retreated to another office, got Cooke on the phone and quickly cut an extension deal with the Lakers that included a no-boxing contract.

Ali and Frazier fought twice more. The second fight was a bore-fest in Madison Square Garden, won by decision by Ali. The third was the Thrilla in Manilla, a brutal slugfest that Ali won by TKO when Frazier didn’t come out for the 15th round, and that hastened the end of each of their careers. When it was over, Ali walked past press row and told a few writers that they had just come close to witnessing death. He meant his.

Izenberg’s lead paragraph on that fight included: “They fought as though they were in a telephone both on a melting icefloe, because they were fighting for the championship of each other.”

Each stumbled out of boxing in the sad way many do. Frazier finished, with a draw that followed two losses, on Dec. 3, 1981. Eight days later, Ali, finishing 1-3 in his last four fights, lost a unanimous decision. A few fights before that, Arum had begged him to quit and actually gave him money to do so.

Frazier never forgave Ali for his slurs, his “Uncle Toms,” the toy gorilla that he held up at press conferences to characterize Frazier. Ali once asked Izenberg to tell Frazier that he apologized for all that, that he was merely promoting their fights. Izenberg did so and Frazier said to tell Ali to “shove” his apologies. As Ali became increasingly ill and incapacitated with Parkinson’s disease, Frazier was asked about it and, instead of expressing sympathy, said the Parkinson’s was “poetic justice.”

Frazier died in 2011 at age 67. Ali, who would live five more years, went to his funeral.

It was their only peaceful meeting, and it was too late.