‘Reintroducing beavers is like throwing petrol on to the bonfire when it comes to nature recovery – it really speeds things up,” says Chris Jones, farmer and communities director of the Beaver Trust. We’re on a tour of Woodland Valley Farm, near Ladock, his home and the site of the Cornwall Beaver Project, where a family of the semi-aquatic mammals live in a five-acre woodland enclosure.

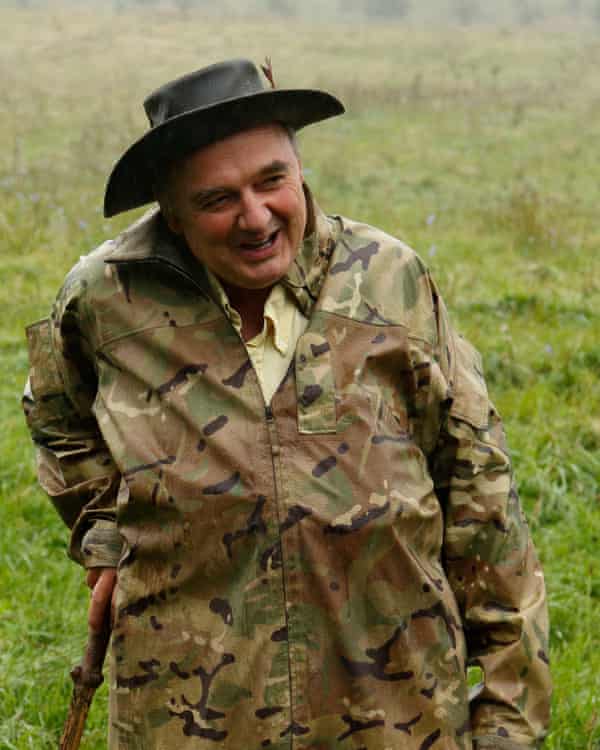

Dressed in wellies, camouflage jacket and floppy hat, Chris speaks with the enthusiasm of the late David Bellamy, pointing out how the landscape has been reshaped. Impressive dams made of wood, stone and mud have slowed the flow of water, new channels have created large pools and new wetland habitat. It feels wild and alive, with signs of recent beaver activity seen in the odd felled tree and piles of woodchip.

“The change is dramatic in just four years,” says Chris. “They engineer the landscape in a way that reduces flooding, helps store water for drought, and boosts wildlife – and wetlands are great carbon sinks.”

Once roaming free across our countryside, the Eurasian beaver became extinct in the UK more than 400 years ago – hunted for fur, meat and glands that contain salicylic acid (prized as a medicinal cure-all). But now, with discussions of how land use and nature restoration can help tackle the climate emergency, and interest in “rewilding” spreading, beaver reintroduction is a hot topic. While recognised in Scotland as a native species, with the largest wild populations living on the River Tay, in England and Wales only licensed enclosures are permitted (there are currently around 20 private and NGO sites) – although a wild population on the River Otter was recently granted permission to stay. A consultation process on beaver reintroduction to England’s rivers is currently going through parliament (anyone can add their voice before 17 November).

“Beavers can do the job of rewilding river and wetland environments with hardly any expense,” says Chris. “The Trust is working with stakeholders, farmers and local communities to see what we can do and listen to everyone’s point of view. There’s a lot of misconception – like they eat fish, for example – and of course some places aren’t suitable, but they should be at the heart of a healthy river environment as they are in much of mainland Europe. We’ve just got used to not seeing them.”

With £2.6 billion spent by the UK government on flood defences between 2015 and 2021, beaver enthusiasts argue they could help at a fraction of the cost, and it was regular floods in Ladock that inspired Chris to explore how he could hold more water on his land. He introduced two beavers in 2017 and, impressed by the results, co-founded the Beaver Trust in 2019 with a team of conservationists, education being a key aim. Besides offering tours, there are converted barns for groups to stay in and wild camping is even allowed in the beaver enclosure.

We wander the site, learning more beaver facts: the second largest rodent in the world (after the capybara), they can weigh up to 30kg, love willow, and their teeth, orange because of iron content, never stop growing. As we stop by a dam, Chris dips a branch into the water slowly flowing downstream and pulls it up covered in silt. “They even do the work of the water companies by stopping many pollutants getting into the water system,” he says.

Chris’s farm is well placed to explore mid-Cornwall – it’s 20 minutes from the Eden Project and close to Truro and St Austell – but our next stop is Cabilla Cornwall, a 300-acre former upland hill farm in the middle of Bodmin Moor with its own ambitious regeneration plans, where beavers also play a part.

Bought by explorer Robin Hanbury-Tenison in the 1960s, and now run by his son Merlin and wife Lizzie, Cabilla opened to guests for the first time in June, offering wellbeing retreats and a place to stay in the wild. There’s a straw-bale cottage to rent and 12 wooden huts will replace the current safari tents from next spring.

Besides the remote, beautiful location, Cabilla has a particularly enchanting attraction: more than 80 acres of temperate rainforest – a habitat rarer globally than tropical rainforest, and today only found in small pockets on Europe’s Atlantic coast. Merlin guides us through a fairytale scene: a forest of gnarled oaks covered by mosses, ferns and lichens, with a meandering river. We climb Cabilla Tor for views over the valley. The air feels so fresh. There’s a sense of this being an ancient place – remnants found of hut circles suggest people lived in these woods 4,500 years ago.

“I used to play in the woods as child,” Merlin says, “but I only realised how healing they are when I was recovering from PTSD after being in the army. I want people to be able to come here and recoup, to simply enjoy the peace and quiet.”

Grand eco-restoration plans for the farm include reforesting another 100 acres with 60,000 trees, while keeping glades and meadows for grazing and wildflowers, with cattle and ponies roaming free. Long-term dreams include bison, wildcats and even lynx. A first step was the introduction of two beavers last summer – Sigourney Beaver and Jean Claude Van-Dam (who now have two kits, Beavie Wonder and Beavie Nicks) – and the benefits are being seen already.

“Creatures have returned that we haven’t seen for years,” says Merlin. “Bird species, reptiles, amphibians, small mammals and fish. The insect explosion has been so exciting as well. Beavers are the foundation of a healthy ecosystem and now that we have them, the valley can finally start to regain the true health and biodiversity it deserves.”

After our woodland tour we return to the heart of Cabilla, a slick, modern conversion of old barns – with open-plan space for yoga, a living room and long wooden tables for dining, where we feast on a colourful plant-based supper.

Dawn and dusk are the best times for beaver watching (and they’re harder to spot in winter), so before first light we join Merlin again to venture into the woods. We negotiate paths through the trees in the beaver enclosure in silence, following a stream until we catch sight of a dam and stop and wait.

It’s not long before, in the demi-light, what at first appears to be a floating log morphs into a rather plump creature gliding gracefully through the water. She climbs on to a bank and is joined by a kit. We watch as they groom, feed and swim. It’s a magical sight – and one that could become commonplace in Britain’s native landscape, if the beaver champions and rewilders get their way.