Five years after a California law allowed doctors to prescribe lethal doses of drugs to terminally ill people who want to end their lives, new legislation introduced Wednesday would make it easier for those who are dying to choose that option.

The bill would speed up the process for patients whose physicians certify they are close to death, and require hospitals that don’t allow physicians to participate to provide patients with information on the law that could include where they can get assistance at another healthcare facility.

“We know that thousands of Californians have been able to access the law, but we also know that there are unfortunately too many unnecessary regulatory roadblocks that are preventing dying patients from being able to access the law,” said Kim Callinan, chief executive of the Compassion and Choices Action Network, a national nonprofit that supports the physician-assisted death law.

Nearly 2,000 Californians with terminal illnesses used the California End of Life Option Act to receive prescriptions for lethal doses during the law’s first three and a half years, according to the most recent data available, and 1,283 of them ingested medication to hasten their death during that period.

Many other terminally ill patients have been unable to obtain such medication before their deaths, Callinan said.

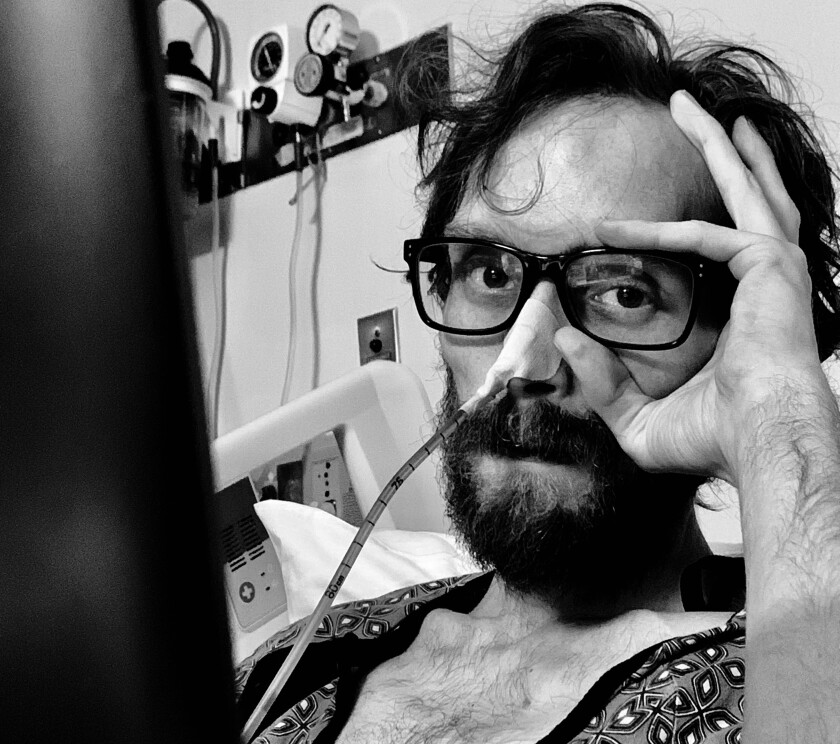

Chris Davis’ last days were very painful despite the pain medication he received, said his wife, Amanda Villegas, above.

(Amanda Villegas)

Those who died before they could complete the 13-step process include Chris Davis, a 29-year-old photographer and preschool instructional aide from Ontario, Calif., who succumbed to complications from bladder cancer in June 2019, according to his wife, Amanda Villegas.

She said her husband asked for a prescription for a lethal dose but the hospital he was in turned down his request, citing questions about the legality of the practice, and said he would have to go through a long process to get another healthcare institution to help.

Davis ran out of time, his wife said, adding that the last 10 days were very painful for him despite pain relief medication he received.

Davis asked for a lethal dose of medication, his wife said, but the hospital turned him down, citing questions about the legality of the practice.

(Amanda Villegas)

“I feel like he had his suffering prolonged extensively,” she said. “I feel like with the [lethal] medication it would have cut some of the suffering and I feel like he wouldn’t have endured so much pain.”

Under the existing law, patients must be diagnosed with less than six months to live, evaluated by two physicians and deemed mentally capable of making their own healthcare decisions. Eligible patients must make two verbal requests at least 15 days apart and one written request that is signed, dated and witnessed by two adults.

The waiting period was included as a concession by the bill’s authors to some concerned lawmakers to provide protections aimed at preventing patients from making rash decisions based on conditions of one moment. Patients must also fill out forms proving their eligibility.

Physicians can refuse to participate, and some have done so after their patients had already gone through much of the process, said state Sen. Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton), who coauthored the 2016 law and is the author of the new bill.

As a result of the regulations, a process that could be completed in as few as 17 days can sometimes take months, preventing patients from getting a prescription before they lose consciousness or die.

“While we want protections in place, we don’t want them to serve as barriers for people who qualify to be able to use it,” Eggman said of the law, which passed after the California Medical Assn. dropped its opposition.

The original bill was opposed by some religious leaders and advocates for the disabled, including Marilyn Golden.

Golden, a senior policy analyst for the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, said Wednesday that she also opposes the new bill, noting that lawmakers behind the original law touted the 15-day waiting period as a safeguard against abuse.

“If the proponents are considering these things to be provisions that lend safety to the patient, why are they now trying to do away with them?” Golden said.

She said the waiting period should not be eliminated because some people have changed their minds when they have had more time to think about ending their life, including cancer patients who have survived their illness and went on to live fulfilling lives.

“There is nobody required to be there when the lethal drugs are actually taken, so no one knows if the person changed their mind and there was coercion in the end,” Golden said.

Eggman said the track record of the program in California shows that many of the opponents’ concerns were unfounded.

“People had a lot of concerns that the bill would be abused, that we would be just killing off older people, that we were going to get rid of disabled people,” Eggman said. “There was a lot of that fear, so we added in a lot of protections.”

She said such abuse did not occur, so she feels justified in authoring a new bill that would waive the 15-day waiting period for those whose doctors don’t think will survive the lengthy process. Eggman said two physicians would still be required to sign off before a prescription is issued.

Oregon waived the 15-day waiting period in 2019 to address concerns that some patients may suffer painful deaths while waiting for approval. Washington and New Mexico are also considering legislation to reduce their waiting periods for patients.

A 2018 study by Kaiser Permanente Southern California looked at 379 patients who initiated inquiries about the end-of-life process during the first year the law was in effect in California and found that 79 — about 21% — later died or were too ill to proceed, 61 were ineligible and 176 were deemed eligible and proceeded with their first spoken request to an attending physician.

The study found that 39 of the patients who made their first spoken request for a prescription died before they could receive the lethal dose, seven were too ill to complete the process and 10 changed their minds.

“Many of the withdrawals at each step of the … process were owing to death or patients being too ill,” said the study, which was published in Journal of the American Medical Assn.

The study said that 74% of those who asked for a prescription had cancer and the two most common reasons for the requests were that the patients did not want to suffer and that they were no longer able to participate in activities that made life enjoyable.

“Instead of allowing them the peace of mind that comes when they get the prescription, we are forcing them to continue to suffer, and they die an agonizing death instead of having the autonomy and compassion that this law affords them,” Callinan said.