The commissioner heading Alberta’s inquiry into alleged foreign-funded attacks on the energy industry is independent and objective and should be allowed to complete the inquiry, a court heard Friday.

“This is not a biased Calgary professional with an agenda. This is a citizen, a laudable citizen,” said David Wachowich, the lawyer for commissioner Steve Allan.

Referencing Allan’s political and charitable donations, Wachowich told Court of Queen’s Bench Justice Karen Horner that Allan defines the role of an engaged citizen “pretty well as much as anybody I know in the city of Calgary in the 30 years that I have been here.”

Environmental law charity Ecojustice sought a judicial review of the inquiry in November 2019, alleging it must be shut down because it is unlawful.

The charity’s case hinges on three arguments: the inquiry was created for improper political purposes, it has been tainted by bias from the beginning, and it deals with matters outside Alberta’s jurisdiction.

On Thursday, the hearing’s first day, Ecojustice lawyer Barry Robinson emphasized the close political association Allan has with both the United Conservative Party and with Justice Minister Doug Schweitzer, who recommended him for the role.

Robinson argued these connections contribute to the inquiry’s reasonable apprehension of bias.

Allan campaigned for Schweitzer, donated to his UCP leadership campaign, co-funded a 2018 political reception for him, and hosted a meet-and-greet with Schweitzer at his home a month before the 2019 provincial election.

Wachowich cited the fact Allan has made political donations to several political parties over the years. He characterized Allan’s political relationship with Schweitzer, who entered provincial politics in 2017, as recent and said it was predicated not on any allegiance to the UCP but on Schweitzer’s “potential utility as an MLA in government.”

As CBC News previously reported, Allan’s personal emails show he tied his political campaign support to Schweitzer publicly supporting the Springbank Dam project, which is to prevent river flooding in Calgary.

That project would directly benefit Allan, whose house in Calgary’s Roxboro neighbourhood was rebuilt after it was destroyed in the 2013 flood.

Wachowich made no mention of Allan’s personal stake in the project. He said Allan, who was chair of Calgary Economic Development at the time, was motivated to “improve living conditions for Calgarians.”

In rebuttal, Robinson said the issue is not whether Allan was a good citizen but whether an objective bystander would believe there was a reasonable apprehension of bias.

He pointed out that Allan had made political donations to a politician and the party that was directly involved in calling the inquiry and selecting Allan to head it.

Robinson also noted that, 19 months after the public inquiry began, Allan has not provided a public list of who he interviewed nor has he listed any reports or studies he has commissioned. This is unlike any public inquiry he has ever seen, he added.

Hearing should be narrowly focused: lawyer

Wachowich said evidence about Allan is largely outside the scope of Ecojustice’s judicial review application.

Both he and the Alberta government’s lawyer say the charity’s proposed legal remedies concern the July 2019 order-in-council that formally established the inquiry and its terms of reference. That order-in-council came from the lieutenant-governor, not Allan.

On Thursday, Ecojustice argued the $3.5-million inquiry is a politically motivated abuse of government authority.

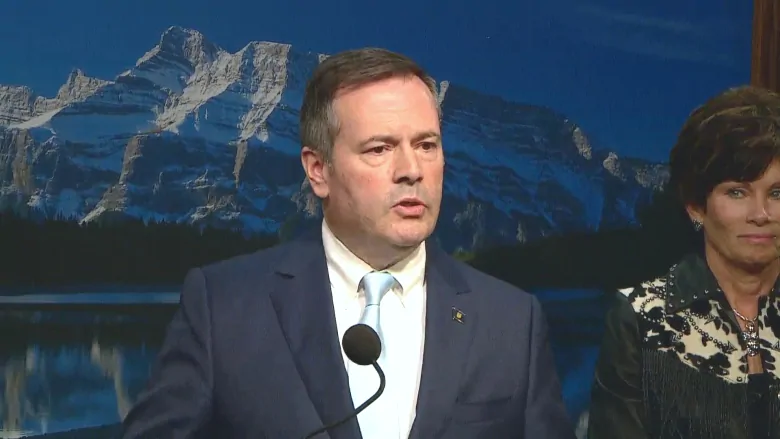

Robinson referenced comments by Premier Jason Kenney, Schweitzer and the United Conservative Party about how the inquiry would “fight back” against certain organizations harming the province’s energy sector.

Those comments, and the wording of the inquiry’s terms of reference, show the inquiry is “adversarial” rather than designed for independent fact-finding as it should be under the law, he said.

“This is a political gunfight intended to target, intimidate, and harm organizations who hold views that differ from those of the government,” he said.

‘No evidence’ commissioner has predetermined view

In her submissions, Alberta Justice lawyer Doreen Mueller said the inquiry is lawful and in the public interest, and the courts shouldn’t interfere.

Robinson had stressed Kenney’s public statement that the inquiry’s findings would be used to go after the charity status of organizations his government considered enemies of the province’s oil and gas industry.

But Mueller insisted the inquiry does not identify or target any specific organization, and there is no intent to harm or punish any individual or group. She said comments made by politicians have no bearing on Allan’s inquiry.

The inquiry is $1 million over its original budget and has blown past three deadlines. Allan must submit his final report to the energy minister by May 31 and it will be publicly released within three months of its submission.

The government has twice amended the inquiry’s terms of reference, ultimately limiting what it is expected to yield. In his September 2020 update to the terms of reference, Allan said he does not have the time or resources to fact-check whether certain statements critical of the province’s energy industry are misleading or false.

Allan’s interpretation of the terms of reference “narrowed his own mandate in significant respects,” Wachowich said, arguing this shows Allan’s independence. He said there is no evidence that suggests Allan has any predetermined view of the issues before the inquiry.

Last month, the inquiry drew widespread scorn for commissioning reports that critics said were full of climate-change denialism, conspiracy theories and oil-industry propaganda.

Ecojustice asked Horner to issue an order barring Allan’s final report from being released before she makes her ruling. Horner declined.

The judge said she would try to issue her ruling before May 31, Allan’s final deadline for the report. But she said if she was delayed, she would hold another hearing on whether the report’s release should be delayed.