ACCRA, Ghana — When the pandemic hit, Ghana called on companies to change gears. Shirtmakers switched to cotton masks. A cosmetics lab churned out hand sanitizer. Dress sewers crafted face shields.

Those goods normally came from Chinese factories, but China had largely closed for business. Beijing’s shipments to Ghana plunged by nearly 50 percent in March, sending the West African nation of 31 million scrambling for backups.

The pivot to medical supplies pumped new energy into a goal that has eluded Ghana since its independence: self-reliance. A more prosperous and less vulnerable future hinges on shaping a nation that “stands on its own feet,” the president said in November — “a Ghana that is beyond dependence on others.”

Global trade fell by nearly a fifth from April to June as assembly lines shuttered and transportation halted. The jolt touched off a succession of harried responses from leaders tempted by dreams of greater autonomy as an alternative to today’s tightly interconnected world.

Relying on overseas factories for survival is “unsustainable,” the French president said. The coronavirus has presented “an opportunity” to shrink the need for outsiders, the Jordanian prime minister said. Boosting domestic production in wake of the crisis is “bad things” evolving to “good ones,” China’s top economic official said.

For Ghana, pandemic-proofing the way forward means building a new manufacturing hub. Core to the mission is shrinking the flow of West African commodities to richer nations that end up reaping the bulk of the profit. About 90 percent of the region’s cotton is shipped to China and its neighbors, which spin and weave it into finished goods.

Most West African cotton is exported to South and Southeast Asia

Share of the majority of raw cotton exported from five West African countries, measured in USD

Share of raw cotton

exports from West Africa

Source: The Atlas of Economic Complexity,

U.N. Comtrade

ATTHAR MIRZA/THE WASHINGTON POST

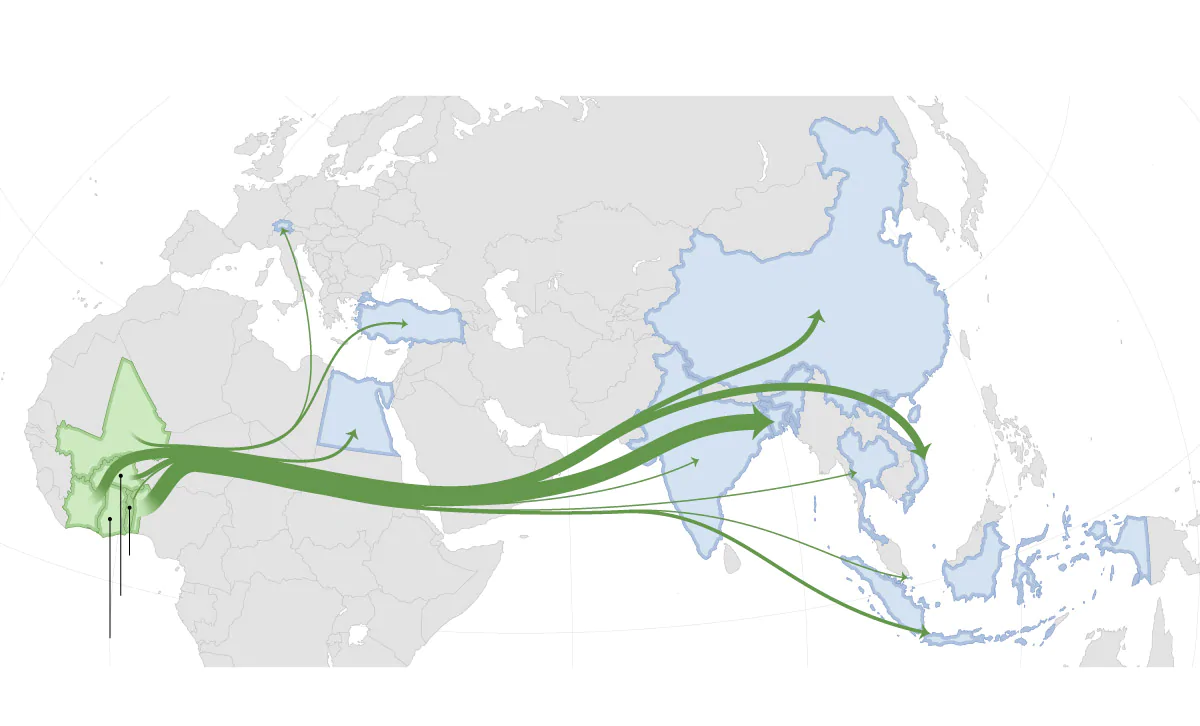

Most West African cotton is exported to South and Southeast Asia

Share of the majority of raw cotton exported from five West African countries, measured in USD

Share of raw cotton

exports from West Africa

Source: The Atlas of Economic Complexity, U.N. Comtrade

ATTHAR MIRZA/THE WASHINGTON POST

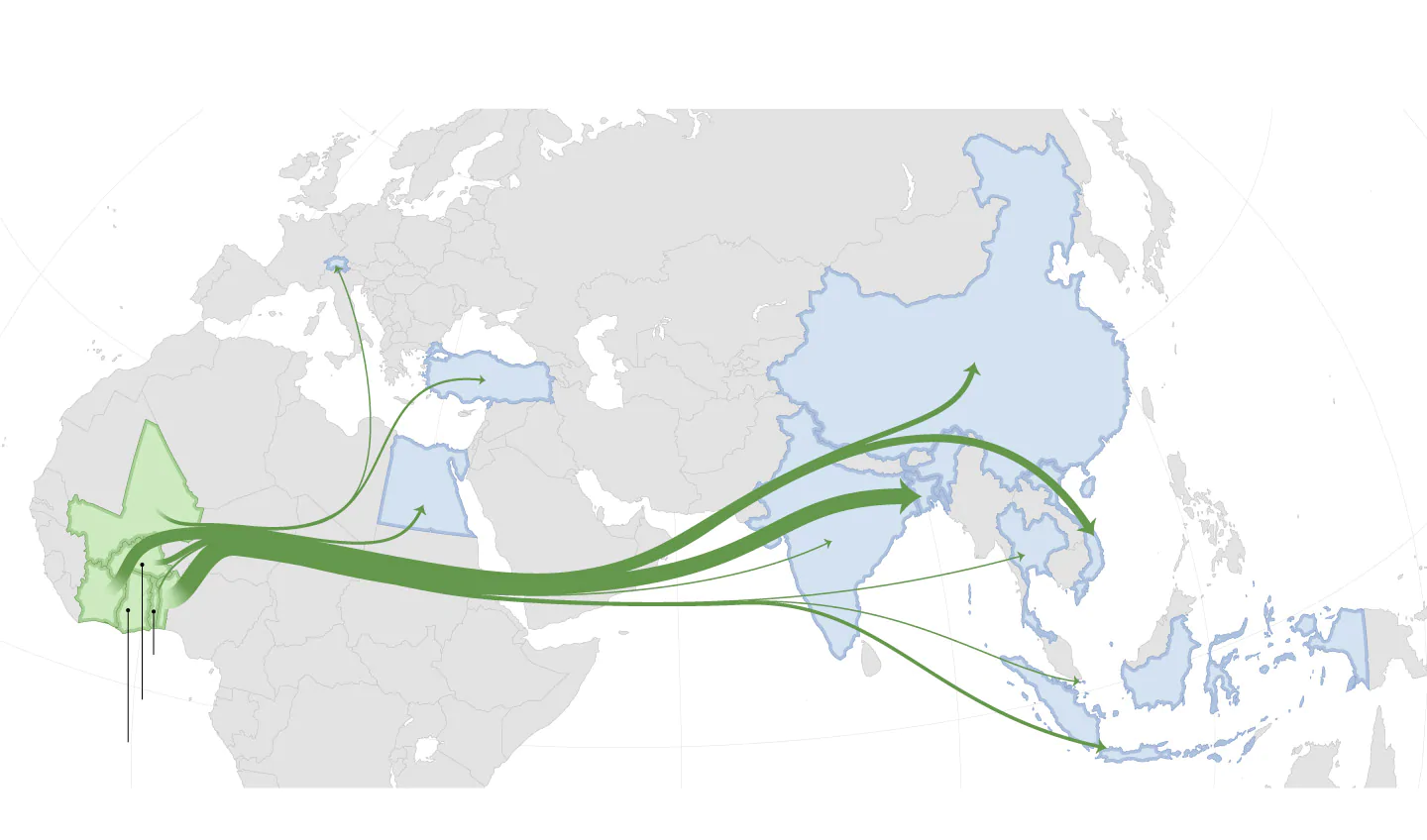

Most West African cotton is exported to South and Southeast Asia

Percentage of raw cotton exported from five West African countries, measured in USD

Source: The Atlas of Economic Complexity, U.N. Comtrade

ATTHAR MIRZA/THE WASHINGTON POST

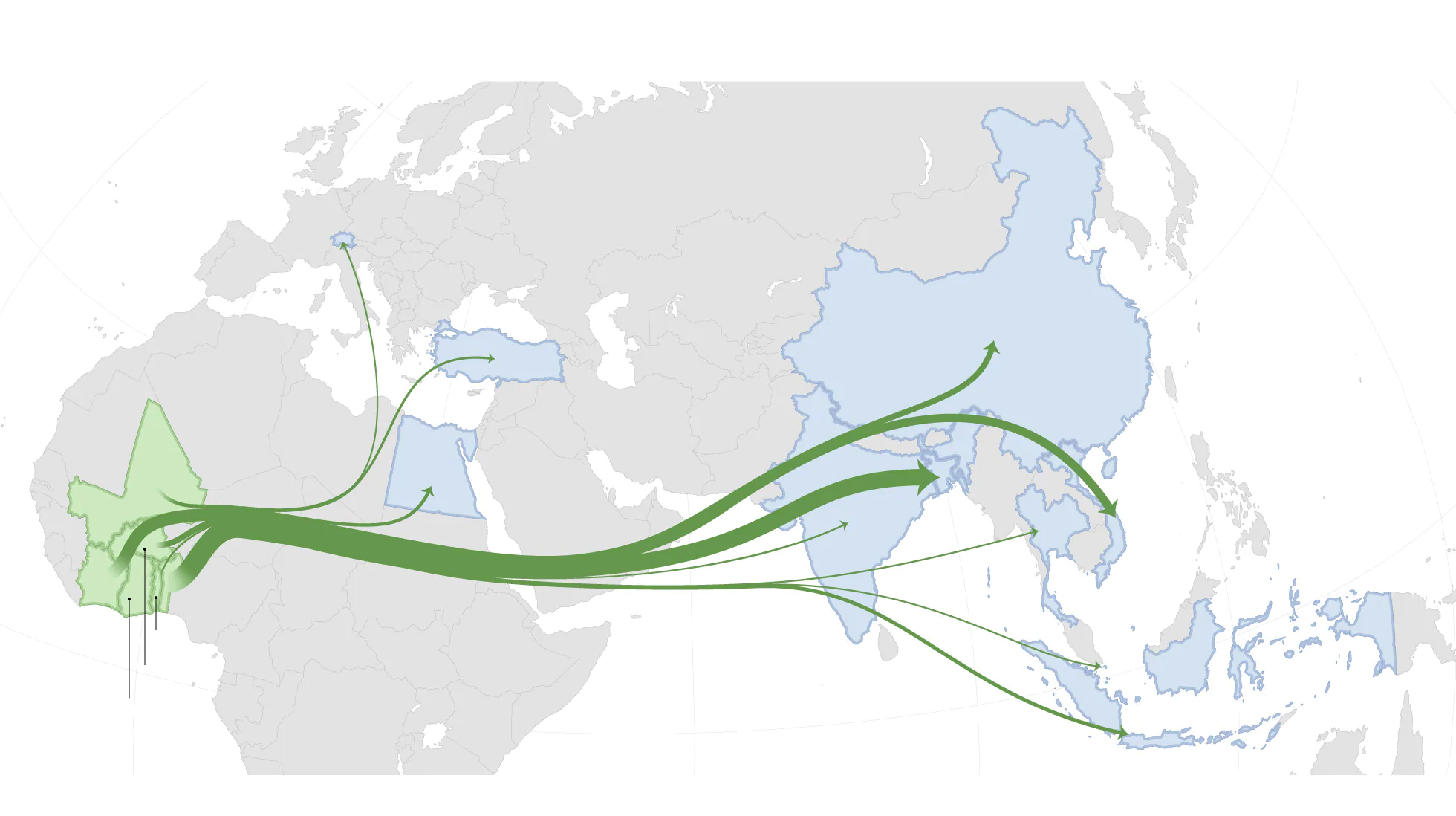

Most West African cotton is exported to South and Southeast Asia

Percentage of raw cotton exported from five West African countries, measured in USD

Source: The Atlas of Economic Complexity, U.N. Comtrade

ATTHAR MIRZA/THE WASHINGTON POST

Most West African cotton is exported to South and Southeast Asia

Percentage of raw cotton exported from five West African countries, measured in USD

Source: The Atlas of Economic Complexity, U.N. Comtrade

ATTHAR MIRZA/THE WASHINGTON POST

Officials want to end that exodus and turn it into a revival.

“We are going to use our resources more effectively, and efficiently, to rapidly transform the economy,” said Yaw Ansu, chief economist emeritus at the African Center for Economic Transformation in Accra, Ghana’s capital, who helped shape the country’s coronavirus recovery plan.

West Africa is the world’s sixth-largest grower of cotton. Chest-high shrubs emerge every dry season in rural swaths of Ghana, Burkina Faso, Mali and Ivory Coast. But the region is equipped to process less than 2 percent of that cotton at home. Creating a clothing supply chain here could boost the industry’s value by 600 percent, according to the West Africa Competitiveness Program in Accra.

Ivorian farmers carry bags full of cotton after a day of picking in early December. West Africa is the world’s sixth-largest grower of cotton, but it is equipped to process less than 2 percent of it. (Issouf Sanogo/AFP/Getty Images)

Ivorian farmers carry bags full of cotton after a day of picking in early December. West Africa is the world’s sixth-largest grower of cotton, but it is equipped to process less than 2 percent of it. (Issouf Sanogo/AFP/Getty Images) Ghana hopes to achieve its upgrades with investors from the private sector — local and international. The recovery plan’s projected cost is 100 billion Ghanaian cedis, or roughly $17 billion, over the next 3½ years.

Mass commercial disruptions this year forced many countries to reckon with supply-chain weaknesses.

Beijing’s lockdown cut off the production of chemicals that India uses to make generic drugs, prompting Indian suppliers to freeze exports of antibiotics and acetaminophen. That sparked drug shortages throughout Europe, compelling the European Commission to launch a probe into its “direct dependence” on pharmaceuticals outside the bloc.

Even China — which has the highest manufacturing output on Earth — bemoaned ruptures. The country is expanding the assembly of semiconductors for phones, televisions and other electronics so it doesn’t have to buy as much from the United States.

Virtually no country can make everything it needs, but the pandemic dealt a blow to decades of confidence about the benefits of international commerce. Back in vogue are quests to thrive without it.

Seizing an opportunity

The path ahead is rooted in an old dream.

Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, inherited an economy in 1957 that ran on British imports. He vowed to replace them with homemade wares.

The former colonial power had padded its wallet for years with Ghana’s natural riches. It was time to wrestle that profit back, Nkrumah said.

Up rose the industrial city of Tema, where the State Textiles Manufacturing Company and other government-backed firms employed thousands of workers. Those early factories crumbled, however, after a 1966 coup ousted Nkrumah, and the nation’s protectionist policies spurred costly, inefficient output.

Then came cheap alternatives from Asia.

China’s economic reforms, which began in 1978, triggered its industrial rise. Garment production in the country saw double-digit growth each year for the next two decades.

The laser focus on exports — with low taxes and shaky regulatory compliance — led to the capture of huge shares of global business: China now accounts for 40 percent of the world’s textile and apparel exports.

A ship unloads containers as a worker checks his cargo list in Tema, an industrial city where the State Textiles Manufacturing Company and other government-backed firms used to employ thousands of workers. These days, Ghana imports most of what it consumes, but leaders hope to reverse that.

TOP: BOTTOM LEFT: BOTTOM RIGHT: A ship unloads containers as a worker checks his cargo list in Tema, an industrial city where the State Textiles Manufacturing Company and other government-backed firms used to employ thousands of workers. These days, Ghana imports most of what it consumes, but leaders hope to reverse that.

Ghana’s cotton mills, meanwhile, rusted away. The country’s 16 large and medium textile firms of the mid-1970s dwindled to four, according to the Brookings Institution.

These days, the nation imports most of what it consumes. Some 70 percent of medicines come from abroad. Frozen chicken arrives from Brazil and rice from Thailand.

Leaders have long pushed to reverse this trend. In a recent presentation for companies around the globe, they touted Ghana’s geographic assets: Packages leaving the Tema port reach American and European buyers weeks faster than those departing hubs like Shanghai. Ghana is a trade-war shelter, they said — commercial pacts with the United States and Europe shield manufacturers from steep tariffs.

The minimum wage is also lower than in China, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Millions are ready to work, officials said, especially after the economy contracted for the first time in nearly four decades.

Plus, the timing is right.

Western companies have signaled a desire to shift supply chains away from China and closer to home, according to a September report from the World Manufacturing Foundation, a research group in Italy. Though that movement took off during the U.S.-China trade war, analysts say the pandemic has encouraged a wider reassessment of global supply-chain risks.

Corporate decisions to spread production out around the world — rather than rely on plants in one place — are expected to create new opportunities for some economies, said Daria Taglioni, a trade economist at the World Bank.

“There aren’t only ruptures,” she said, but “creations of new links.”

Ghana intends to seize on the reshuffling, said Ansu, the economist in Accra.

“We are going to develop areas where we have a competitive advantage,” he said.

That’s where cotton comes in. The crop contributes to a $786 billion global-manufacturing apparel market and supports hundreds of thousands of small growers across West Africa, who mostly harvest by hand.

The low-tech approach gives the crop an advantage: Eighty percent is classified as superior grade, according to an analysis of international quality standards by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, a British nonprofit.

Absent a rough automated touch, the fiber is more likely to stay intact, shiny and free of chemical grime.

Global history shows that the textile industry is a gateway to wealth for budding economies, said Alan Kyerematen, the country’s trade minister.

“We believe it will also work for Ghana,” he said.

Luring investors

To spin the white fluff into yarn and weave it into cloth, Ghana needs cotton mills, and few exist here. Those that do exist operate at partial capacity. New operations cost up to $200 million, according to the Tony Blair Institute.

But Ghana’s push to lure investors is working, Kyerematen said: Investors with the cash for the latest machines are circling. Seven firms have approached the government in recent months.

After the pandemic struck, the nearly 200 workers at Sixteen47 learned to make cloth masks and face shields. The firm also took orders that used to go abroad — labels, bank uniforms, political T-shirts — from new clients fed up with shipping delays. “Now I’m realizing we could make literally anything,” said owner Nura Salifu.

TOP LEFT: TOP RIGHT: BOTTOM LEFT: BOTTOM RIGHT: After the pandemic struck, the nearly 200 workers at Sixteen47 learned to make cloth masks and face shields. The firm also took orders that used to go abroad — labels, bank uniforms, political T-shirts — from new clients fed up with shipping delays. “Now I’m realizing we could make literally anything,” said owner Nura Salifu.

Some are from Turkey and the United States, including the American retail giant PVH — home of Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger. (The company declined to comment on the specifics.)

Most interest, though, is coming from the global textile champion itself: China.

China’s textile market is saturated, and investors there are looking to get in early elsewhere, said Willy Shih, a professor of technology and operations management at Harvard Business School. The Chinese government encourages investors to explore new markets like Ghana and even pays for trips abroad.

“A lot of Chinese entrepreneurs are going for: What is the next China?” Shih said. “They want to ride that wave because they have seen friends and relatives get rich.”

Some of Ghana’s efforts to draw private money have already brought in more business. Akosombo Industrial Company Limited — one of the only textile factories that survived the nation’s manufacturing downturn — plans to upgrade its fabric mill and expand by as much as 30 percent, thanks to technical and machinery deals with Chinese and German partners.

Most of its starter cloth today comes from Asia, but the upgrade, executives say, is expected to change that. The company, which occupies 70 verdant acres to the north of Accra, pumps out bolts of colorful vibrant prints for shirts, dresses and special-occasion looks.

The ambition is contagious. Nura Salifu, a 34-year-old garment factory owner in Accra, sources fabric from Akosombo for women’s clothing. Her business, Sixteen47, heeded the government’s call and transformed when the pandemic struck.

Salifu’s team of nearly 200 learned to make cloth masks and face shields from YouTube videos. Then they soaked up all kinds of orders that used to go abroad — labels, bank uniforms, political T-shirts — from new clients fed up with shipping delays.

“Covid gave us confidence,” Salifu said on a recent afternoon, as her staff stitched military fatigues. “Now I’m realizing we could make literally anything.”

Orders are up 200 percent, she said, and she plans to move Sixteen47 into a bigger space. She’s courting potential investors whom she hopes will be persuaded by Ghana’s tax breaks.

“I don’t want to go back to the way it was before,” Salifu said.

Fabric should be made in Ghana, she said — perhaps right under her roof. The next goal: her own cotton mill.