The number of Americans hospitalized for Covid-19 is at its lowest since early November, just before the surge that went on to ravage the country for months.

There were 56,159 people hospitalized as of Feb. 21, according to the Covid Tracking Project. That’s the lowest since Nov. 7. It’s a striking decline for a nation that is approaching 500,000 total deaths and once had some of the world’s worst coronavirus hot spots.

While deaths remain high, because it can take weeks for patients to die from Covid-19, the number of U.S. hospitalizations has steadily and rapidly declined since mid-January, when the seven-day average reached about 130,000, according to a New York Times database. Experts attributed that peak to crowds gathering indoors in colder weather, especially during the holidays, when more people traveled than at any other time during the pandemic.

Experts have pointed to a variety of explanations for why the country’s coronavirus metrics have been improving over the past few months: more widespread mask use and social distancing after people saw friends and relatives die, better knowledge about which restrictions work, more effective public health messaging, and, more recently, a growing number of people who have been vaccinated. The most vulnerable, like residents of nursing homes and other elderly people, were among the first to receive the vaccine.

While scientists hope the worst is behind us, some warn of another spike in cases in the coming weeks, or a “fourth wave,” if people become complacent about masks and distancing, states lift restrictions too quickly or the more contagious variants become dominant and are able to evade vaccines.

The change can be felt most tangibly in intensive care units: Heading into her night shift in the I.C.U. at Presbyterian Rust Medical Center in Rio Rancho, N.M., Dr. Denise A. Gonzales, the medical director, said she had seen a difference in her staff.

“People are smiling. They are optimistic,” she said. “They’re making plans for the future.” During the worst of the crisis, “working in such a highly intense environment where people are so sick and are on so much support and knowing that statistically very few are going to get better — that’s overwhelming.”

Though the winter wave that hit her hospital system was “twice as bad” as the summer surge, she said it seemed more manageable because hospitals had prepared to move patients around, staff had more knowledge about P.P.E. and treatment therapies, and facilities had better airflow.

At the CoxHealth hospital system in Springfield, Mo., there was a “moment of celebration” as staff emptied the emergency Covid-19 I.C.U. wing built last spring. “We have not defeated this disease,” said Steve Edwards, the system’s chief executive. “But the closing of this unit, at least for now, is a tremendous symbolic victory.”

Staff members wearing biohazard suits and heavy-duty masks were pictured in a rare moment of relief and joy that Mr. Edwards shared on Twitter.

This is a moment of celebration as we vacated the emergency Covid ICU. Our number of Covid patients at Cox South has dropped to 43, and only 5 critical. We are mindful of future worries, but for now, HERE COMES THE SUN! pic.twitter.com/57t2TvWweB

— Steve Edwards (@SDECoxHealth) February 18, 2021

Dr. Kyan C. Safavi, the medical director of a group that tracks Covid-19 hospitalizations at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said the number of newly admitted patients has dropped sharply. The hospital is admitting about 10 to 15 new patients daily, a decline of about 50 percent from early January, Dr. Safavi said.

“Everybody’s physically exhausted — and probably a little bit mentally exhausted — but incredibly hopeful,” Dr. Safavi said.

LONDON — Prime Minister Boris Johnson of Britain is expected to confirm on Monday that schools in England will reopen on March 8 and that people will be allowed to socialize outdoors on March 29, the first steps in a long-awaited reopening plan after a nationwide lockdown prompted by a highly contagious variant of the coronavirus.

Mr. Johnson’s “road map” is intended to give an exhausted country a path back to normalcy after a dire period in which infections skyrocketed, hospitals overflowed with patients, and the death toll surged past 100,000. At the same time, Britain rolled out a remarkably successful vaccination program, injecting 17 million people with their first doses.

That milestone, combined with a steep decline in new cases and hospital admissions, paved the way for Mr. Johnson’s announcement. But the prime minister has emphasized repeatedly that he planned to move slowly in reopening the economy, saying that he wanted this lockdown to be the last the nation had to endure.

Under the government’s plan, pubs, restaurants, retail shops, and gyms in England will stay closed for at least another month — meaning that, as a practical matter, daily life will not change much for millions of people.

“Our decisions will be made on the latest data at every step,” Mr. Johnson said in remarks issued by his office Sunday evening, “and we will be cautious about this approach so that we do not undo the progress we have achieved so far.”

The specific timetable will hinge on four factors: the continued success of the vaccine rollout; evidence that vaccines are reducing hospital admissions and deaths; no new surge in infection rates that would tax the health service; and no sudden risk from new variants of the virus.

Mr. Johnson is to present the plan to Parliament on Monday afternoon and to the nation in an evening news conference, along with data that is expected to show how the vaccination program has affected the spread of the virus. That will end days of speculation.

But it is likely kindle a new round of debate about whether the government is easing restrictions fast enough.

With pubs and restaurants not expected to be allowed to offer indoor service until May and attendance at sporting events not permitted before June, some members of Mr. Johnson’s Conservative Party are likely to revive their pressure campaign to lift the measures more quickly.

Mr. Johnson, however, appears determined to avoid a repeat of his messy reopening of the economy last May after the first phase of the pandemic. The government’s message was muddled — workers were urged to go back to their offices but avoid using public transportation — and some initiatives — like subsidizing restaurant meals to bolster the hospitality industry — looked reckless in hindsight.

By November, cases were climbing again, and the government reluctantly announced another lockdown. Britons went through further mixed signals before Christmas when Mr. Johnson pledged to relax restrictions so families could celebrate together, only to pull back amid a new surge in infections.

In January, after a variant first detected in Kent, in southeastern England, had spread like wildfire through the country, Mr. Johnson hastily imposed an even tougher nationwide clampdown, ordering people to stay at home, except for essential activities. Schools that had reopened after the holiday were abruptly closed again.

On Monday, Mr. Johnson will address at least that issue.

“Our priority has always been getting children back into school, which we know is crucial for their education as well as their mental and physical well-being,” he said in the remarks released by his office. “We will also be prioritizing ways for people to reunite with loved ones safely.”

Scotland’s vaccination program substantially reduced Covid-19 hospital admissions, according to the results of study released on Monday, offering the strongest real-world signal of the effectiveness of the AstraZeneca-Oxford vaccine that much of the world is relying on to end the pandemic.

The study, encompassing both the AstraZeneca and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, examined the number of people who were hospitalized after receiving a single dose of the vaccine. Britain has delayed administering the second dose for up to three months after the first, opting to offer more people the partial protection of a single shot.

But the study sounded a cautionary note about how long high protection levels from a single dose would last. The risk of hospitalization dropped starting a week after people received their first shot, reaching a low point four to five weeks after they were vaccinated. But then it appeared to rise again.

The scientists who conducted the study said it was too early to know whether the protection offered by a single dose waned after a month, cautioning that more evidence was needed.

The findings in Scotland bolstered earlier results from Israel showing that the vaccines offered significant protection from the virus. The Israeli studies have focused on the Pfizer vaccine, but the Scottish study extended to the AstraZeneca shot, which has been administered in Britain since early January. The AstraZeneca shot is the backbone of many nations’ inoculation plans: It is far cheaper to produce, and can be shipped and stored in normal refrigerators rather than the ultracold freezers used for other vaccines.

“Both of these are working spectacularly well,” Aziz Sheikh, a professor at the University of Edinburgh who was involved in the study, said at a news conference on Monday.

The researchers in Scotland examined roughly 8,000 coronavirus-related hospital admissions, and studied how the risk of hospitalization differed among people who had and had not received a shot. Over all, more than 1.1 million people were vaccinated in the period the researchers were studying.

The numbers of vaccinated people who sought care in hospitals was too small to compare the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines, or to give precise figures for their effectiveness, the researchers said.

But from 28 to 34 days after the first shot, the AstraZeneca vaccine reduced the risk of Covid-19 hospital admissions by roughly 94 percent. In that same time period, the Pfizer vaccine reduced the risk of hospitalizations by roughly 85 percent. In both cases, those figures fit within a broad range of possible effects.

Because the Pfizer vaccine was authorized in Britain before the AstraZeneca shot, the researchers had more data on the Pfizer vaccine, and found that the protection against hospital admissions was somewhat reduced at longer periods after the first shot.

“The peak protection is at four weeks, and then it starts to drop away,” said Simon Clarke, a professor in cellular microbiology at the University of Reading who was not involved in the study.

The AstraZeneca vaccine has faced skepticism in parts of Europe after many countries chose not to give it to older people, citing a lack of clinical trial data in that group. The Scottish study could not offer precise figures on that vaccine’s effectiveness in older people. But the combined effect of the AstraZeneca and Pfizer vaccines substantially reduced hospital admissions in people over 80. Many older people were given the AstraZeneca vaccine.

The U.S. economy remains mired in a pandemic winter of shuttered storefronts, high unemployment and sluggish job growth. But attention is shifting to a potential post-Covid boom.

Forecasters have always expected the pandemic to be followed by a period of strong growth as businesses reopen and Americans resume their normal activities. But in recent weeks, economists have begun to talk of something stronger: a supercharged rebound that brings down unemployment, drives up wages and may foster years of stronger growth.

There are hints that the economy has turned a corner: Retail sales jumped last month as the latest round of government aid began showing up in consumers’ bank accounts. New unemployment claims have declined from early January, though they remain high. And measures of business investment have picked up.

Economists surveyed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia this month predicted that U.S. output would increase 4.5 percent this year, which would make it the best year since 1999. Some expect an even stronger bounce: Economists at Goldman Sachs forecast that the economy would grow 6.8 percent this year and that the unemployment rate would drop to 4.1 percent by December, a level that took eight years to achieve after the last recession.

“We’re extremely likely to get a very high growth rate,” said Jan Hatzius, Goldman’s chief economist. “Whether it’s a boom or not, I do think it’s a V-shaped recovery,” he added, referring to a steep drop followed by a sharp rebound.

The growing optimism stems from several factors. Coronavirus cases are falling in the United States. The vaccine rollout is gaining steam. And largely because of trillions of dollars in federal help, the economy appears to have made it through last year with less structural damage than many people feared last spring.

Consumers are also sitting on a trillion-dollar mountain of cash, a result of months of lockdown-induced saving and rounds of stimulus payments.

“There will be this big boom as pent-up demand comes through and the economy is opening,” said Ellen Zentner, chief U.S. economist for Morgan Stanley. “There is an awful lot of buying power that we’ve transferred to households to fuel that pent-up demand.”

Even if there is a strong rebound, however, economists warn that not everyone will benefit.

Standard economic statistics like the unemployment rate and gross domestic product could mask persistent challenges facing many families, particularly the Black and Hispanic workers who have borne the brunt of the pandemic’s economic pain. That could lead Congress to pull back on aid when it is still needed.

It seemed at first like a small, no-frills concert in a carefully controlled environment: the jazz musician Jon Batiste sitting at a piano in an auditorium at the Javits Convention Center on Manhattan’s West Side, performing for an audience of about 50 health care workers — some wearing scrubs, others Army fatigues.

But about half an hour in, Mr. Batiste and other performers stepped off the stage and exited the room, turning what had begun as a formal concert into a rollicking procession of music and dancing that grooved through the sterile building — the convention center was turned into a field hospital early in the pandemic and is now a vaccination site — where hundreds of hopeful people had come on Saturday afternoon to get their shots.

This concert-turned-roaming-party was the first in a series of “pop-up” shows in New York intended to give the arts a jolt by providing artists with paid work and audiences with opportunities to see live performance after nearly a year of darkened theaters and concert halls.

Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo announced plans for the series, called “NY PopsUp,” last month, declaring that “we must bring arts and culture back to life,” and adding that their revival would be crucial to the economic revival of New York City.

Because the program is wary of drawing crowds, most of the performances will be unannounced, emerging suddenly at parks, museums, parking lots and street corners. The idea is to inject a dose of inspiration into the lives of New Yorkers.

As the musicians moved through the convention center, the audience of health care workers followed them, clapping to the beat and recording the spectacle on their phones.

Shortly before the music ended, some health care workers rushed off to continue their work day (this concert was happening during their break time, after all).

The French Riviera, the famed strip along the Mediterranean coast that includes jet-setting hot spots like Saint-Tropez and Cannes, will be locked down over the next two weekends in an attempt to fight back a sharp spike in coronavirus infections.

France has been under a nighttime curfew since mid-January and restaurants, cafes and museums remain closed, but the government of President Emmanuel Macron has resisted putting a third national lockdown in place.

It has been a calculated gamble, with Mr. Macron hoping that he could tighten restrictions just enough to stave off a new surge of infections without resorting to the more severe rules in place in many other European countries.

The strategy has largely worked, but infection rates remain at a stubbornly high level of about 20,000 new cases per day. Officials have made it clear that the existing national restrictions would not be loosened and that more local lockdowns could be enforced in the coming days.

The French Riviera, which includes the city of Nice, has the country’s highest infection rate, and officials have grown increasingly alarmed as they surged to 600 cases per week per 100,000 residents — about three times the national rate.

“The epidemic situation has sharply deteriorated,” Bernard Gonzalez, a regional official for the Alpes-Maritimes area, said on Monday as he announced the lockdown, which will affect the coastal area between the cities of Menton and Théoule-sur-Mer.

Officials said that controls at the border with Italy, in airports and on roads would be toughened and that the police would carry out random coronavirus tests. New measures also include a closure of all larger shops and an acceleration of the vaccination campaign.

Infection rates surged as many French people flocked to the coast, attracted by the temperate Mediterranean weather as they sought to escape gloomy cities like Paris.

“We will be happy to receive lots of tourists this summer, once we win this battle,” Christian Estrosi, the mayor of Nice, said last week. “But it is better to have a period while we say ‘Do not come here, this is not the moment.’”

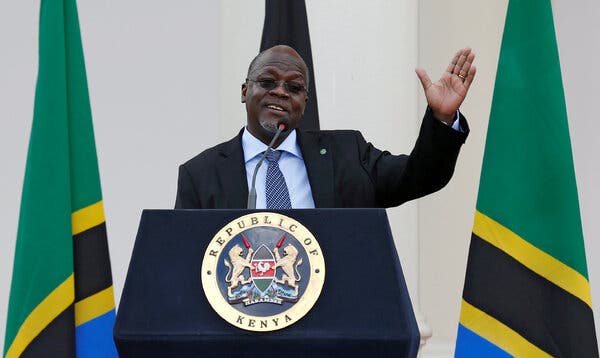

NAIROBI, Kenya — Officially, Tanzania has not reported a single coronavirus case since April 2020. According to government data, the country has had only 509 positive cases and 21 deaths since the start of the pandemic.

Almost no one believes those numbers to be credible. But they fit with President John Magufuli’s declaration that the pandemic was “finished.”

Now, facing criticism from the World Health Organization and skepticism from the public as Tanzanians take to social media to voice concern about a growing number of “pneumonia” cases, Mr. Magufuli is changing course and asking people to take precautions against the coronavirus and wear masks.

Speaking during a church service in the port city of Dar es Salaam, the president asked congregants to continue praying for the disease to go away but also urged them to follow “advice from health experts.”

In a statement released by his office, Mr. Magufuli said his government had never barred people from wearing masks but urged them to use only those made in Tanzania.

“The masks imported from outside the country are suspected of being unsafe,” the statement said.

Mr. Magufuli’s comments come a day after the director-general of the World Health Organization urged the country to start reporting coronavirus cases and share data.

Mr. Magufuli, 61, who was re-elected last October, has derided social distancing, publicized unproven treatments as a cure for the virus, questioned the efficacy of coronavirus testing kits supplied by the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and said that “vaccines don’t work.”

Yet health experts, religious entities and foreign embassies have issued warnings about the rising number of cases — and as deaths follow, the reality is harder to dismiss.

The vice president of the semiautonomous island of Zanzibar, Seif Sharif Hamad, died last week after contracting the virus, according to his political party. The United States Embassy in Tanzania also said in a statement it was “aware of a significant increase in the number of Covid-19 cases” since January.

Lawmakers are increasingly asking the health authorities to explain why so many people were dying from respiratory problems.

Speaking on Friday at the funeral of a government official, however, Mr. Magufuli said that citizens should put God first and not be instilled with fear about the virus.

“It is possible that we wronged God somewhere,” he said. “So let’s stand with God, my fellow Tanzanians.”

In his statement, the W.H.O. chief, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said he had spoken to “several authorities” in the country about their plans to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus but had yet to receive any response.

“This situation remains very concerning,” he said.

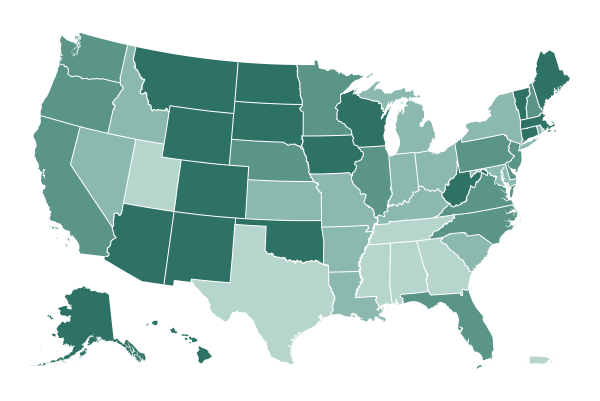

Around the United States, the vaccine rollout has reflected the same troubling inequalities as the pandemic’s death toll, leaving Black, Latino and poorer people at a disadvantage. In New York City, home to more than three million immigrants from all over the world, data released last week suggests that vaccination rates in immigrant enclaves scattered across the five boroughs are among the city’s lowest.

This month, The New York Times interviewed 115 people living in predominantly immigrant neighborhoods about the rollout and their attitudes toward the vaccines.

Only eight people said they had received a shot. The interviews revealed language and technology roadblocks: Some believed there were no vaccine sites nearby. Others described mistrust in government officials and the health care system. Many expressed fears about vaccine safety fomented by news reports and social media.

The broader public may find it difficult to understand why people in communities ravaged by the coronavirus would be reluctant to line up to get vaccinated, said Marcella J. Tillett, the vice president of programs and partnerships at the Brooklyn Community Foundation.

“This is where there has been a lot of illness and death,” said Ms. Tillett, whose foundation is distributing funds to social service organizations for vaccine education and outreach. “The idea that people are just going to step out and trust a system that has harmed them is nonsensical.”

To be sure, thousands of immigrant New Yorkers have gotten vaccinated, navigating the system with patience, if not ease. Others have relied on social service organizations. BronxWorks recently held a five-day vaccine pop-up on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, administering hundreds of shots each day.

To increase participation in immigrant enclaves and communities of color, the city has opened vaccine mega-sites at Yankee Stadium in the Bronx and Citi Field in Queens, which offer vaccinations to eligible residents of each borough. (There have been reports of suburbanites coming in to claim doses.)

The state is holding online “fireside chats” in several languages, opening new sites in Brooklyn and Queens, and continuing to bring pop-up sites to neighborhood organizations.

Still, obstacles remain.

As France raced to complete a complex blueprint in December for vaccinating its population, the government quietly issued millions of euros in contracts to the consulting giant McKinsey & Company.

The contracts, which were not initially disclosed to the public, were intended to help ensure that vaccines would make their way quickly to distribution points for nursing homes, health care providers and the elderly. Additional contracts were hastily awarded to other consultants, including Accenture and two firms based in France.

But within weeks, the country’s vaccination campaign was being derided for being far too slow. In early January, France had inoculated only “several thousand people,” according to the health minister, compared with 230,000 in Germany and more than 110,000 in Italy.

As the consulting contracts came to light, McKinsey has become a magnet for controversy in a country where an elite civil service is expected to manage public affairs, and private-sector involvement is viewed with wariness.

The contracts — totaling 11 million euros ($13.3 million), of which €4 million went to McKinsey — were confirmed by a parliamentary committee this month. The government of President Emmanuel Macron, which has been under fire for months for stumbling in its handling of the pandemic, was forced to admit it had turned to consulting firms.

On Wednesday, 18 lawmakers from the conservative party Les Républicains sent a letter to Mr. Macron seeking further answers about why McKinsey was hired.

The letter cited McKinsey’s recent agreement to pay nearly $600 million to the authorities in the United States to settle claims that it contributed to “the devastating opioid crisis” as a concern for its involvement in French health matters.

A spokesman for McKinsey declined to comment.

Mr. Macron, a former investment banker, came into office promising to operate one of Europe’s biggest governments with greater efficiency. Its response to the coronavirus pandemic has been criticized inside France for being the opposite, with repeated lockdowns, supply shortages and a failure last summer to put in place a critical triptych of testing, tracing and isolation.

No one is accusing McKinsey of wrongdoing. The company has rolled out its pandemic consulting services in other countries, including Britain and the United States. But to critics of the French government’s strategy, the performance raises questions over the value that consultants add to the process.

Frédéric Pierru, a sociologist and researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research who has studied the impact of consulting firms, said that the companies tended to import operating models used in other industries that weren’t always effective in public health.

“It’s too early to tell if McKinsey and others are adding value in this campaign,” he said. “But I think we’ll never really know.”

When the Paycheck Protection Program began last year, the Trump administration — eager to get money out the door as quickly as possible — eliminated most of the safeguards that normally accompany business loans. With applications approved almost instantly, thieves and ineligible borrowers siphoned billions of dollars from the $523 billion the program distributed last year.

In December, Congress approved $284 billion for a new round of lending, including second loans to the hardest-hit businesses. This time, the Small Business Administration was determined to crack down. Instead of immediately approving applications from banks, it held them for a day or two to verify some information.

That caused — or exposed — a cascade of problems. Formatting applications in ways that will pass the agency’s automated vetting has been a challenge for some lenders, and many have had to revise their technology systems almost daily to keep up with adjustments to the agency’s system. False red flags, which can require time-consuming human intervention to fix, remain a problem.

The problems can be even more complicated for applicants seeking second loans who flew through the process the first time despite errors that are being discovered only now.

Nearly 5 percent of the 5.2 million loans made last year had “anomalies,” the agency said last month, ranging from minor mistakes like typos to major ones like ineligibility. Even tiny mistakes can spiral into bureaucratic disasters.

In mid-February, the agency began allowing lenders to essentially override many of its error flags and self-certify the eligibility of borrowers tangled in red tape. It also has a dedicated help line for lenders, but that, too, has been overwhelmed.

Lenders and government officials believe the program’s funding will be enough to meet demand. The first Paycheck Protection Program ran out of funding in less than two weeks. This time, more than one month in, the program has disbursed less than half of the available money.

But the clock is ticking: Lending is scheduled to end March 31. That deadline has spooked some borrowers who fear they will not get their problems resolved in time.

Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, and other top officials received the Sinovac coronavirus vaccine on Monday as the semiautonomous Chinese territory prepares to begin its mass inoculation campaign this week.

Hong Kong has made deals to buy 7.5 million doses each of the Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Sinovac vaccines, more than enough to inoculate its population of 7.5 million people. While the Pfizer and Sinovac vaccines have both been authorized by the Hong Kong government, AstraZeneca is still awaiting approval.

Widespread vaccinations are set to begin on Friday, with health care workers, people over 60, and nursing home residents and staff members receiving them first. But the Hong Kong public has shown growing hesitancy toward vaccines, with one survey last month showing that more than half of respondents did not plan to get vaccinated. An even larger proportion of residents said they would not take the Sinovac shot, which was developed by a private Chinese company and has faced scrutiny over a lack of data from late-stage clinical trials.

Mrs. Lam has urged all Hong Kong residents to get vaccinated and said that they would be able to choose which vaccine they receive.

Unlike Mrs. Lam and many other world leaders, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, has not publicly received a vaccination. Hua Chunying, spokeswoman for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, declined to say whether Mr. Xi or the premier, Li Keqiang, had been vaccinated. But she noted that officials from Bahrain, Egypt, Indonesia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and other countries had publicly received the Sinovac vaccine.

Separately, the Philippines said on Monday that it had granted emergency use authorization for the Sinovac vaccine, with the first shipment of 600,000 doses set to arrive within days. Eric Domingo, director of the Food and Drug Administration, said that because the Sinovac vaccine had a lower efficacy rate among health care workers at risk of exposure to the virus, it was not recommended for that group, local news outlets reported. It is the third coronavirus vaccine to be approved in the Philippines, after Pfizer and AstraZeneca.