In 2015, federal prosecutors in Los Angeles made a deal with the CEO of one of Southern California’s most dangerous industrial facilities, a battery recycling plant that had contaminated thousands of nearby homes with lead dust.

Exide Technologies agreed to demolish its plant in Vernon and pay $50 million to cover the costs of decontaminating the site and cleaning up the mainly working-class Latino enclaves it had polluted. In return, prosecutors spared the company and its executives from criminal charges.

Neighbors cheered the plant’s closure. But five years later, Exide declared bankruptcy and a federal judge allowed it to abandon the contaminated facility. The building still stands today. The cleanup is unfinished and being financed by California taxpayers. Prosecutors and state environmental regulators disagree over whether the company violated its deal, but the dispute is academic — there’s no company left to prosecute.

Federal prosecutors’ deal with Exide was so remarkable that an EPA official hopped on a plane to California to try to stop it. Agreements not to charge companies that promise to make amends are rare in the world of environmental crime, where prosecutors who can’t make a persuasive criminal case can pursue corporate polluters in civil court.

But in Los Angeles — where prosecutors cover a region of heavy industry hubs, the nation’s busiest port complex and historically harmful levels of air pollution — the Exide case was not an outlier. According to a Los Angeles Times review of environmental criminal cases brought by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Central District of California, prosecutors there have made more such deals with corporations accused of violating environmental laws than in any of the 93 other such offices in the country.

Companies in these cases weren’t required to plead guilty; they weren’t convicted of any crimes, according to the agreements. Instead, the government agreed to forego prosecution for a certain time period or drop the case altogether if the companies paid hefty fines and promised to clean up the environmental damage they had inflicted.

Critics of these deals, known as deferred prosecution or nonprosecution agreements, say they give corporations a pass.

“If you’re the classic U.S. attorney, you want to convict an individual of a serious crime. That gives rise to accountability and deterrence,” said John Coffee, a Columbia University law professor who has written about the drawbacks of these deals. “Deferred prosecution and nonprosecution agreements don’t do that.”

The federal Environmental Protection Agency has historically opposed these agreements. In a 2006 memo to investigators, the agency’s director of criminal enforcement wrote that deferred and nonprosecution agreements essentially allowed companies to “buy their way out of a criminal conviction” and should only be used in “truly exceptional circumstances.”

Though the Justice Department has sanctioned these agreements and uses them in financial fraud cases, as well as other types of proceedings, prosecutors in the department’s environmental crimes section have typically rejected them as overly lenient.

The federal government doesn’t keep a list of the deferred or nonprosecution agreements it has made. But researchers at the University of Virginia and Duke University law schools have created a database to track the criminal prosecution of corporations. According to that registry, federal prosecutors have made only 17 such deals out of more than 700 environmental and wildlife cases since the late 1990s. The Times found two more nonprosecution agreements through a Freedom of Information Act request.

Eight of those deals, or roughly 40%, came out of the Central District of California, a rate far out of proportion to its share of the country’s environmental caseload, according to a summary of environmental prosecution data maintained by Syracuse University’s TRAC project. Three of the eight agreements were made in the last two years.

Though these types of agreements can be used to entice corporate boards to assist the government in pursuing criminal charges against executives, none of the Central District cases resulted in enforcement against business owners or high-level employees.

“The classic rationale is missing,” Coffee said. “This appears to just be a policy of letting companies off without a criminal conviction.”

A U.S. attorney’s office spokesman said deferred and nonprosecution agreements can be an effective deterrent and even advantageous when compared to taking a case to trial, which carries the risk of an acquittal or a judge imposing a lesser penalty. The deals guarantee that polluters will pay, said spokesman Thom Mrozek, even if they avoid the stigma of a criminal conviction.

“We believe that obtaining [deferred and nonprosecution agreements] — along with monetary penalties, corporate compliance agreements, and other provisions — reflects an aggressive pursuit of cases that another office may simply decline,” Mrozek wrote in a statement.

A protestor wears a mask during a 2013 rally demanding the shutdown of Exide Technologies.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

The Exide case shows the value of these agreements, he said. Prosecutors feared that if they filed criminal charges, Exide would go bankrupt and taxpayers would have to shoulder the entire cost of the cleanup. The deal they struck “was the only viable option to both shut down the facility and keep the company as a viable entity,” he wrote.

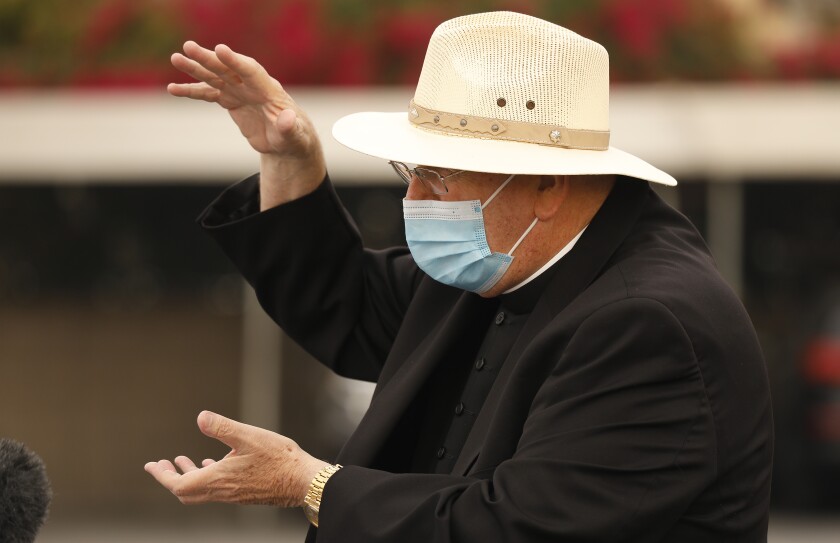

Residents in the contaminated neighborhoods near Exide initially agreed with prosecutors’ strategy, believing it was the only way to close the plant after decades of neglect by California environmental regulators, said Msgr. John Moretta of Resurrection Catholic Church in Boyle Heights, where some churchgoers believe their health problems are a result of exposure to neurotoxins from Exide. But after the company escaped both criminal liability and the obligation to fully fund the cleanup, Moretta said, his views shifted.

Msgr. John Moretta, shown at an October 2020 news conference on Exide’s bankruptcy, says the company’s agreement with prosecutors now seems like “a bum deal.”

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

“In retrospect, as the famous Monday morning quarterback, I’d say it was a bum deal,” Moretta said. “I’m not an attorney, but I can say there probably was another way to do it that would have been more punitive to Exide.”

Most of the Central District’s other deals didn’t attract any attention. Several involved little-known cosmetics manufacturers in the San Fernando Valley accused of hazardous waste violations. One concerned a waste hauler, Asbury Environmental Services, accused of discharging marine diesel oil into a storm drain that led to the Los Angeles River. In 2020, 10 years after that incident, prosecutors wrapped up the case with a nonprosecution deal.

“Long before any government action, Asbury completely remediated the impact of the incident and implemented numerous safety protocols,” a company spokesman said in a statement.

In one case that did receive public scrutiny, Trump administration Justice Department officials reportedly intervened in 2019 to block prosecutors from charging the agrochemical giant Monsanto with a felony, according to reporting by the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan organization based in Washington. Although Monsanto had been accused of illegally spraying a toxic pesticide in Hawaii, a conflict of interest in the Hawaii federal prosecutor’s office led to the case being handled by prosecutors in the Central District.

Instructed to reduce the charges against Monsanto to misdemeanors, according to the watchdog organization, prosecutors in L.A. worked out a deal that left open the possibility of future felony charges. Monsanto ultimately pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor charge and prosecutors used a deferred prosecution agreement to extract a $10 million fine from the company, according to a November 2019 news release from the U.S. attorney’s office. If the company sticks to its compliance plan, the felony charges against it will be dismissed at the end of this year.

A spokesman for Bayer, the German chemical company that owns Monsanto, declined to comment.

Prosecutors’ willingness to make these deals is notable, former Justice Department prosecutors said, because for decades, the Central District was known for aggressively targeting environmental criminals. Its jurisdiction is massive, spanning Los Angeles County — the most populous in the U.S. — and six others, including Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties. By its own account, the office has the only stand-alone section of environmental crimes prosecutors outside of the Justice Department in Washington.

But there have been dramatic declines in environmental prosecutions nationwide, and the unit no longer focuses solely on environmental crime. Although federal prosecutors in L.A. still bring more criminal cases against polluters and wildlife traffickers than most other large districts, Mrozek said the majority of the 28 cases the section filed last year fell under the category of “community safety.”

Federal prosecutors and former EPA officials said the office’s environmental section has become an increasing source of frustration for the Justice Department and the EPA. Like the Southern District of New York — nicknamed the Sovereign District — the Central District has earned a reputation for operating independently from its counterparts in Washington.

Its use of nonprosecution and deferred prosecution agreements has, at times, created tension.

Doug Parker, who oversaw EPA’s criminal investigation division from 2012 to 2016, said the agency viewed these types of deals as “an escape hatch from criminal liability.”

“Oftentimes, we would prefer civil resolutions to nonprosecution agreements,” he said, adding that they carry “stronger enforcement mechanisms.”

When he learned that Joseph Johns, assistant U.S. attorney and then-chief of environmental crimes for the Central District since 2006, planned to sign a nonprosecution agreement with Exide, Parker got on a plane to L.A. to try to change Johns’ mind.

He returned to Washington discouraged. “This was not one we were going to be beating our chests about, saying what a great result,” Parker said.

Johns resigned as chief of the environmental section in January, but will continue to work on environmental cases. His former deputy, Mark Williams, was recently chosen as the section’s new chief, Mrozek said. He declined to give more specifics on Johns’ resignation, citing the office’s policy of not discussing personnel matters. Through Mrozek, Johns and Williams turned down requests to be interviewed for this story.

Another example of L.A. prosecutors’ approach took place in 2019, when Coast Guard investigators found evidence that crew members on a container ship at the Port of Los Angeles had been dumping oily bilge water into the sea. The indictment prosecutors filed said the crew had failed to maintain the ship’s oil record book, where they should have documented their actions — a violation of maritime pollution law.

The crew worked for Capital Ship Management, a publicly traded Greek company that operates a fleet of 50 vessels. Workers on one of its oil tankers had been caught in a similar violation just two years earlier, also in L.A., and prosecutors had settled that case without charging the management company.

Now a ship managed by the same company stood accused of another environmental crime.

According to current and former federal prosecutors, the Justice Department’s playbook for vessel cases calls for prosecutors to target a ship’s management company on the theory that it’s responsible for the crew’s behavior onboard. Federal prosecutors are also instructed that the best way to get a shipping company to stop befouling the ocean is to require it to follow an environmental compliance plan covering a large portion of its fleet, making it impractical for the company to sell a single implicated vessel and abandon its promises to change its behavior.

But federal prosecutors in L.A. didn’t use that strategy. Under the nonprosecution deal they struck, one of Capital Ship Management’s subsidiaries pleaded guilty, agreed to pay a fine and signed onto a compliance program that applied to only one ship. Capital Ship Management avoided all criminal liability.

Mrozek said prosecutors had weighed all their options and chosen the best outcome.

It certainly wasn’t a perfect case — the defense filed motions raising evidentiary problems that could have made it difficult for prosecutors to win a conviction. In the end, two of the ships’ crew members had pleaded guilty to felony charges. The fines paid totaled $1 million. “We believe justice has been served in a case involving a single water pollution incident,” Mrozek said.

Capital Ship Management’s defense attorney, George Chalos, felt pretty good too. For the second time in two years his client had dodged a criminal conviction in L.A. Chalos said the company didn’t know what its crew was doing and prosecutors had acted justly by not holding it responsible.

“It was unusual for the prosecutors,” he said. In subsequent cases, he said, he has asked Justice Department prosecutors in Washington to agree to the same terms. But Chalos said they wouldn’t bite.

“They’ve come in and said: ‘Don’t even ask for what you got in L.A. Don’t even ask.’”