When the 10 correctional officers charged in the death of an Inuk man at a jail in St. John’s face a judge for the first time in February, Gordon Wheaton says he’d like to be there.

Wheaton is a former inmate of Her Majesty’s Penitentiary, the jail in which Jonathan Henoche was killed on Nov. 6, 2019. He said he spent two days with Henoche in a cell in the jail’s special handling unit in 2018.

Abuse is commonplace at the provincial penitentiary, the result of a justice system that does more harm than good, he said in an interview Tuesday.

“I want them held accountable,” he said of the 10 guards charged with crimes ranging from manslaughter to criminal negligence causing death. “We need to change the system. Thing is, nobody’s helping us.”

Henoche was 33 when he died after a reported altercation with corrections officers. He was awaiting trial for charges including first-degree murder in relation to the 2016 death of an 88-year-old woman in Labrador.

Last week, the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary announced ten officers had been charged in connection with Henoche’s death — but they did not release the officers’ names because the charges had not been sworn in court.

Police said the officers were released without a bail hearing and are due before a judge on Feb. 11.

Wheaton said it’s outrageous the officers were able to spend Christmas with their families. “I’m glad there was arrests, but I’m also disgusted by how it was handled,” he said, adding that he wasn’t surprised.

Nor was he surprised, he added, by Henoche’s death inside the jail.

“The place is just a fuse box ready to explode,” he said. “When guards are abusive and the place you’re in is horrible, then bad things happen.”

Wheaton said he was jailed in 2018 for uttering threats. He said Henoche was brought to his cell because all the others in the unit were full. “He wanted to stay down in the (special handling unit) because he was having problems with people upstairs,” Wheaton said, adding that he knew Henoche had been charged with murder.

After two days together, Wheaton said Henoche was sent back into the regular population.

Wheaton, who served a 30-day sentence, said some guards at the provincial jail are good to inmates, but many, he said, are not. Some officers belittle and antagonize inmates, sometimes denying them basics like towels, Wheaton said, adding that guards can be particularly cruel to inmates suffering from mental health issues.

“There’s no medical help down there at all,” he said. “It’s a way to prevent you from speaking out about your mental health.”

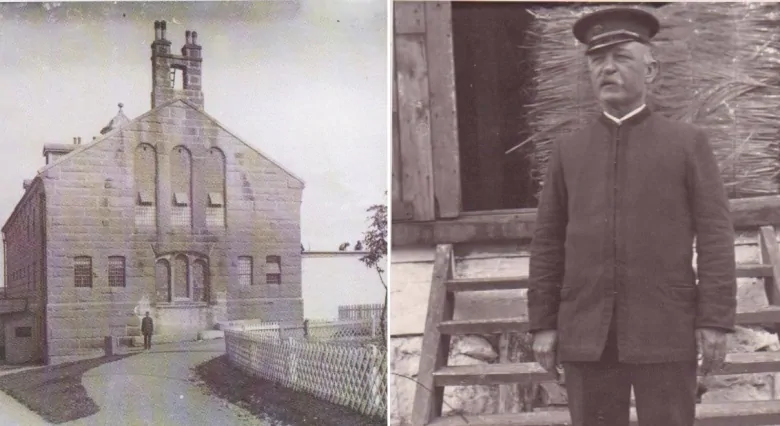

Infrastructure problems at HMP ‘well known’

Wheaton said that inside the 161-year-old facility, the cell toilets regularly flood and mice scramble across the floors. His concerns are echoed in a February 2019 report commissioned after a rash of suicides in Newfoundland and Labrador correctional facilities, two of which occurred at Her Majesty’s Penitentiary.

Retired police superintendent Marlene Jesso said overcrowding, limited services and insufficient training have contributed to a mental health crisis among inmates. The report also singled out a negative attitude toward inmates among HMP staff.

Just before his suicide at HMP in 2018, inmate Chris Sutton wrote to the province’s human rights commission, pleading for help in confronting abuses he said were taking place, particularly with respect to the use of segregation and solitary confinement.

In September, a class-action lawsuit was launched against the province on behalf of inmates held in solitary confinement for periods longer than two weeks. The lawsuit claims negligence by the government in ensuring the safety and well-being of inmates.

Justice Department spokeswoman Danielle Barron said Tuesday HMP’s infrastructure problems are “well known.” In an emailed statement, Barron said the province is forging a public-private partnership to build a new prison, construction on which will begin 2022.

She did not speak directly to Wheaton’s allegations of abusive and cruel treatment by guards.

“Correctional officers receive mental health awareness training, mental health first aid, and are trained in suicide intervention,” she said. “We recently hired a training manager to ensure training is provided to meet the needs of an ever-changing inmate population.”

A spokesperson for the union representing corrections officers at the jail said it could not comment at this time.

Wheaton lives in Clarenville but said he’s willing to make the roughly two-hour drive to St. John’s for the guards’ appearance in court. He said he’s worried that the bulk of the people who’ll be there will be supporting the guards and not standing up for Henoche.