Ex terra lucem. Light from the ground. St Helens has the finest motto in England. It evokes the town’s long mining history, its world-leading glass industry – which used, as well as coal-fired furnaces, the fireclays beneath the coal measures – and, now that so many of our working-class heroes have passed on, the illumination to be gleaned from communing with wise ancestors.

That, anyway, is how I like to think of a new mining themed walk on an app, Landscape Legacies of Coal Mining, developed by historian Dr Catherine Mills of the University of Stirling. The three-mile route (with an optional two-mile extension) through Bold Forest Park – the 1,780 hectare (4,400-acre) area that surrounds the famous Dream statue by Jaume Plensa – adds a new seam of interest. Former miner Jim Housley, 60, wrote the texts for the St Helens walk, which peeks behind the tree cover and carefully planned parkland to reveal the park’s previous life as Sutton Manor colliery.

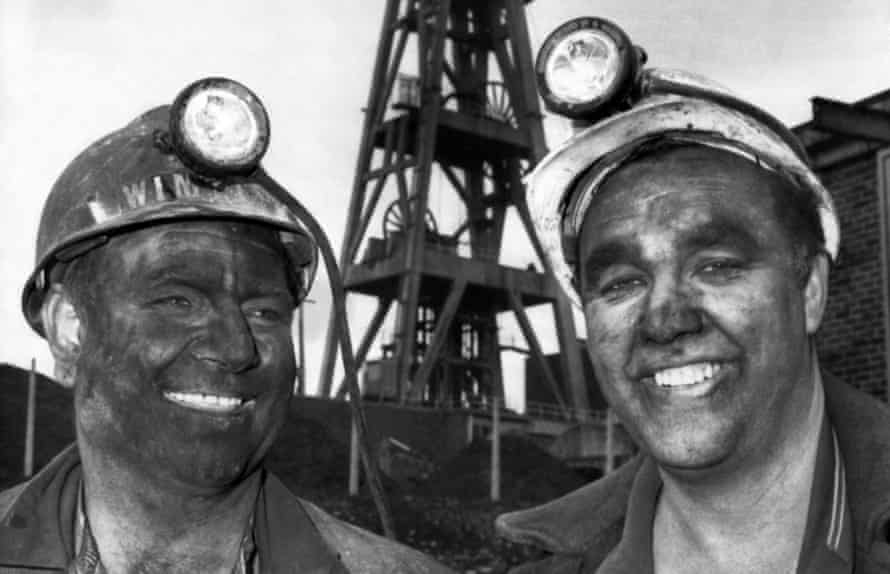

“I worked at Sutton Manor from 1981 until 1991, when it closed and I was made redundant,” says Jim. “My dad wouldn’t let me go down the pit when I left school, so I joined the navy. When I came back I went down the pit at Sutton Manor as a chock fitter [responsible for maintaining roof supports], the same job as my dad. He was basically my boss.

“I did the app because people long for the sense of community they associate with those times. I want to get more local people to use the park, partly to get them to understand the past so that they can appreciate what they’ve got now. But I also want them to come and appreciate the wildlife, nature and open space.”

We set off on the walk, which has 23 coal mining digital information stops, as well as notes on the construction of Dream and further panels on the wider area. I flit between Jim’s chatter and the texts on the app, which has a map and a few pictures. I’m guided from the entrance to the grand old colliery gates, past where the bath-house lockers – where the men changed and got their lamps and helmets – would have been. Then, it’s over to the shafts that took them down and brought the coal tubs up.

My dad was a miner and, like many of his tribe, he almost never talked about the day-to-day aspects of his job. It’s affecting to be on the site of a colliery that – in its 1960s heyday – employed 1,500 men and produced 600,000 tonnes of coal each year. The cage that went down the shaft took them more than 550 metres beneath the ground, where they would set off on locomotives or on foot several miles to the coal face.

“Every pit has its own character and each face is different, which we call the ‘run of the coal’,” says Jim. “This was quite a gassy pit. Sometimes it would have to be closed to clear the gas. It was warm, if not as hot as some others. Sometimes men would work in their undies, if it was too hot.”

Two miners’ ashes were scattered just where the shafts have been capped. Red-coloured wreaths lie at the spot. An information board close to the entrance notes that when the pit – which had been there since 1906 – was shut down despite having plenty more coal to give, local people felt Sutton Manor had “lost its soul”.

Jim and other ex-miners have formed the Northwest Miners Heritage Association, which works closely with other local groups and the Lancashire Mining Museum at Astley Green to help recover this soul. Some members turn up to show me a replica of the parade banner used by the miners at Sutton Manor.

“The banner’s a focal point for people and whenever we unfurl it, the community spirit comes out,” says Jim. “Nobody’s got a bad word to say about miners. Everybody around here has connection with them and I think they long for some of the community spirit of the past time. Of course people say it was better then, but I wouldn’t want to go down the pit again.”

This, of course, is the great paradox of commemorating industrial history. Coal mining generated a vast amount of the planet’s past carbon emissions, and the IEA found that CO2 emitted from coal combustion was responsible for over 0.3C of the 1C increase in global average annual surface temperatures above pre-industrial levels, making it the single largest source of global temperature increase. Coal enslaved young children in the early years of the Industrial Revolution, and has killed thousands of workers and caused many millions to die young. But to forget coal’s contribution would be to bury the complex truth along with all its victims.

The walk up to the Dream statue, over landscaped slag that has been made into a fair size tump, is gentle. At the top is the imposing white moai, towering over the West Lancashire Coastal Plain, as well as fresh air and birdsong. Between the trees you can make out Warrington’s sprawl, the Winter Hill transmitter, the cooling towers of the decommissioned Fiddler’s Ferry power station (soon to be demolished) and, somewhat closer, the M62. Jim says Forestry England, which manages the site, will trim the treetops to create better sightlines.

One of our last stops is at a large area of hardstanding, where colliery lorries used to be loaded with sacks; the cement is broken up by hardy ruderals, the walls spattered with graffiti. Jim, who is a talented painter, says they could be used to display coal-themed murals.

“There’s a lot of potential. We could have a place for people to hire mobility scooters or bikes. We’re thinking of planting a tree that could be hung with miner’s tallies [the metal tokens used for clocking on and off]. The abandoned miners’ institute next door could be a cafe and space for memorabilia. The rangers here are very supportive, as is the council.”

St Helens was a full-scale industrial hub from the mid-19th century until the 1980s, when the Conservative government effectively shut the town down. The app reveals how Sutton Manor was once crisscrossed by railways sidings; a detailed map shows the path of the Runcorn Gap railway, which ran down to the Mersey. Bike lanes and footpaths now occupy the lines, and the council is to be credited for creating a network of open spaces suited to physical activity.

You might think older miners – the few that are left – would be resistant to digital technology, but Jim says this is not the case. “An old miner who can’t get up here now can look at the app and walk it in his head. His granddaughter can go and do the walk and then they can talk about it.”

The app currently contains 21 walks, most in Scotland, such as the Brucefield Colliery at Clackmannan, Newtongrange (home of the National Mining Museum Scotland), and no fewer than three Alloa Waggonway walks. Jim plans to add guided walks to Sutton Manor’s neighbouring collieries at Bold and Clock Face and to add more nature notes to all the walks.

“While the heritage of the coal industry is well represented at national level, the local histories often slip under the radar,” says Mills. “Curated heritage walks on a mobile phone app permit a local focus and offer an ideal medium both for individuals and community groups to express issues around their local industrial heritage, and to promote active engagement with the landscape.

“Importantly, unlike a book or leaflet that remains static from the day of publication, the app with its expandability and dynamic processes also provided a novel method to continually record the rapidly disappearing landscape features and industrial archaeology.”

This is surely what the web and smart tech were made for. I was never taught about coal mining at school, and the app will have immense value to schoolchildren across the country, as well as curious local people. I’ve read books on coal mining, but this adds a new aspect to learning about this important part of our heritage – alongside a visit to the site itself.

Download the app for iOS or Android. You can read more about it at the University of Stirling website. OS Explorer map 275 shows how Bold Forest Park links to the wider region through footpaths, canal paths and cycleways