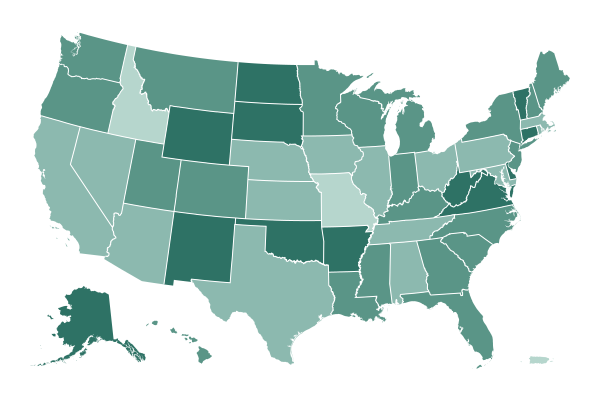

Vaccinations in the United States are slowly picking up speed as the Biden administration pushes to accelerate inoculations and blunt the spread of more contagious virus variants.

The United States has administered about 30 million doses, and, as of Sunday, is averaging more than 1.3 million doses administered over the past seven days, compared with an average of less than one million per day two weeks earlier, according to a New York Times vaccine tracker.

President Biden, under pressure to speed up coronavirus vaccinations, has recently suggested the nation could soon reach an average of 1.5 million shots a day.

But just as there are signs of progress, another problem has taken root: the spread of the variants, which scientists warn must be contained before they become dominant. Several hundred cases of the more contagious variant discovered in Britain, which experts have said could be the dominant form in the United States by March, have already been confirmed.

The country has also recorded its first two cases of the variant spreading rapidly in South Africa, which has proved to reduce the effectiveness of vaccines.

“If we didn’t have these variants looming,” we would be in a good place, said Dr. Peter Hotez, a vaccine scientist and pediatrician at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. If those variants take over by spring, “as many of us are predicting,” he said, “it changes everything. Now, we really have to vaccinate the American population by late spring, early summer.”

Two key challenges in the weeks ahead are “increasing the supply of vaccines” and “speeding up the time it takes to administer them,” Andy Slavitt, a White House adviser, said in a news briefing on Friday. Many experts have pushed for bringing other vaccine options out and releasing the first doses more widely.

The most effective state programs, said Dr. Ashish Jha, the dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, are “very simple, age-based, not a lot of complex rules. They focus on getting the vaccines out.”

Here is a snapshot of how five of the best-performing states are doing:

-

West Virginia has given at least one dose to 10.7 percent of its population, second only to Alaska, and leads the nation in the percentage of its population that has received two doses (3.7 percent). Early on, the state got a head start because it opted out of a federal program to vaccinate people in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. While other states chose the federal plan, which teamed with Walgreens and CVS, officials decided the idea made little sense in West Virginia, where many communities are miles from the nearest chain store, and about half of pharmacies are independently owned. Instead the state created a network of pharmacies, pairing them with about 200 long-term care facilities.

-

According to health officials in Alaska, there are several reasons behind the state’s relatively high vaccination rate, The Anchorage Daily News has reported. Those factors include: the state’s having received a high number of doses through the Indian Health Service; the decision to receive doses monthly, versus weekly, as most states do; and declining virus caseloads, which has allowed health care workers to focus on inoculations. The state has vaccinated 13 percent of its population, according to a Times database.

-

North Dakota has used 91 percent of the vaccines distributed to the state, according to the Times vaccine tracker. It is the only state above 90 percent; more populous states like California (58 percent) and New York (64 percent) have used less, proportionally. North Dakota was among the first states to lower the minimum age eligible for vaccination, from 75 to 65.

-

In a recent interview with the American Medical Association, health officials in New Mexico attributed part of the state’s success to its “data-oriented and science-oriented” governor, Michelle Lujan Grisham, and to an app that allowed easy registration and close coordination among hospitals and providers. The state has given 9.8 percent of residents at least one shot, and has used 83 percent of its doses.

-

Connecticut got mass vaccination sites up and running early, and uses an inventory system that allocates unused doses to places that need them. But older residents have complained about long waits.

PARIS — Public frustration with lockdowns is palpable across Europe, with pensioners protesting this weekend in Vienna, restaurateurs taking to the streets in Budapest and demonstrators clashing with the police in Belgium, prompting dozens of arrests. The Dutch authorities fined more than 10,000 people last week for violating the national curfew.

While none of the protests resulted in the kind of violence seen in the Netherlands in recent weeks, they reflect a growing impatience as political leaders extend restrictions to guard against a resurgence of the virus fueled by new variants.

In France, President Emmanuel Macron has resisted a full lockdown, making a calculated gamble that his government can tighten the rules just enough to avoid a new wave of infections.

Prime Minister Jean Castex appeared in front of television cameras for an unexpected statement on Friday night, announcing a handful of new curbs, including strict border closures.

“Even if the path is very narrow, we must take it,” Mr. Macron was reported to have said at a cabinet meeting last week, according to the Journal du Dimanche, pushing back against the advice of several senior aides. According to the newspaper, he added: “When you are French, you have all you need to get by, as long as you dare to try.”

Polls in France have shown weariness with restrictions, and grumbling about the rules is growing in some quarters.

France is still under a 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew, and places like cafes, museums and theaters are closed. Schools and shops are open.

After a widely publicized breach of the rules at a restaurant in the southern city of Nice last week and a call to “civil disobedience” by some restaurant owners, the French economy minister, Bruno Le Maire, warned on Monday that any establishments that flouted the rules would be cut off from coronavirus aid.

In the French Alps, protesters blocked roads on Monday to demand that ski lifts reopen.

Critics say that Mr. Macron’s approach may simply be delaying the inevitable and that he could be forced to change course if cases started to surge.

“It’s a risk, I’m hoping it was a calculated risk,” Karine Lacombe, an infectious-disease specialist, told the French news channel LCI on Sunday.

Mr. Macron’s plan is rooted partly in the relative stability of the pandemic in France. The number of new daily cases has inched up only slowly and while hospitalizations remain high, there has been no sudden surge. More contagious variants of the virus have been registered in the country, but the authorities say they believe that their spread, so far, is under control.

“Everything suggests that a new wave could occur because of the variant,” Olivier Véran, the French health minister, told the Journal du Dimanche. “But perhaps we can avoid it thanks to the measures that we decided early and that the French people are respecting.”

Aurelien Breeden reported from Paris, and Marc Santora from London.

transcript

transcript

N.Y.C. Snowstorm Delays Vaccinations

On Monday, Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York postponed coronavirus vaccinations to prevent older residents from traveling to appointments in blizzard-like conditions.

-

The storm is disrupting our vaccination effort, and we need to keep people safe. We don’t want folks, especially seniors, going out in unsafe conditions to get vaccinated. We know we can reschedule appointments very quickly because, of course, we have supply. We’re going to use the supply we have. Our problem is lack of supply. So we can take the supply we have and distribute it very quickly in the days to come, and make sure everyone gets the appointments. But it’s not safe out there today. So vaccinations are canceled today. They’re also going to be canceled tomorrow. Based on what we are seeing right now, we believe that tomorrow, getting around the city will be difficult, it’ll be icy, it’ll be treacherous. We do not want seniors, especially, out in those conditions. So we’re going to have vaccinations off for today and tomorrow, come back strong on Wednesday. We’ll be able to catch up quickly because, again, we have a vast amount of capacity. We don’t have enough vaccine. So we’ll simply use the days later in the week. Crank up those schedules, get people rescheduled into those days.

Mayor Bill de Blasio of New York said on Monday that coronavirus vaccinations scheduled for Tuesday would be postponed because of the winter storm, the second day in a row that they have been delayed.

Heavy snow was also complicating vaccination efforts in Washington, Philadelphia, New Jersey and elsewhere.

At a news conference on Monday, Mr. de Blasio of New York City said he did not want older residents traveling to vaccine appointments amid blizzard-like conditions with gusty winds.

“Based on what we are seeing right now, we believe tomorrow, getting around the city will be difficult,” Mr. de Blasio said. “It will be icy, it will be treacherous.”

He said he believed the city could quickly make up the appointments later in the week.

“We have a vast amount of capacity; we don’t have enough vaccine,” he said. “We’ll simply use the days later in the week, crank up those schedules, get people rescheduled into those days.”

The storm will temporarily derail a vaccine rollout that has been plagued by inadequate supply, buggy sign-up systems and confusion over the New York State’s strict eligibility guidelines. The vaccine is available to residents 65 and older as well as a wide range of workers designated “essential.”

About 800,000 doses have been administered so far in the city, Mr. de Blasio said.

Vaccine appointments originally scheduled for Monday at several sites in the region — the Javits Center in Manhattan, the Aqueduct Racetrack in Queens, a drive-through site at Jones Beach in Long Island, SUNY Stony Brook and the Westchester County Center — would be rescheduled for this week, according to a statement from Melissa DeRosa, a top aide to Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo. “We ask all New Yorkers to monitor the weather and stay off the roads tomorrow so our crews and first responders can safely do their jobs,” she said.

Mr. Cuomo said at a news conference on Monday that New York’s seven-day average positive test rate was 4.8 percent, the 24th straight day it had declined.

Mr. Cuomo added that the state had administered about 1.96 million doses of the vaccine.

In the Philadelphia area, city-run testing and vaccine sites were closed on Monday. Connecticut, New Jersey, Rhode Island and parts of the Washington, D.C., area were following suit. Some areas away from the center of the storm were expected to remain open for vaccinations, including parts of Massachusetts and upstate New York.

The past few weeks in the United States have been the deadliest of the coronavirus pandemic, and residents in a majority of counties remain at an extremely high risk of contracting the virus. At the same time, transmission seems to be slowing throughout the country, with the number of new average cases 40 percent lower on Jan. 29 than at the U.S. peak three weeks earlier.

Other indicators reinforce the current downward trend in cases. Hospitalizations are down significantly from record highs in early January. The number of tests per day has also decreased, which can obscure the virus’s true toll, but the positivity rate of those tests has also gone down, indicating that the slowed spread is real.

Still, the average reported daily death rate over the past seven days remains above 3,000, compared with less than 1,000 per day in September and October.

Experts say the decrease could mark a turning point in the outbreak after months of ever-higher caseloads. But new, more contagious variants threaten to upend progress and could even send case rates to a new high if they take hold, especially if the national vaccine rollout faces hurdles.

transcript

transcript

Biden to Discuss Pandemic Relief Package With Republicans

President Biden will meet with 10 Republican senators on Monday who have proposed a much smaller Covid-19 relief package. Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, told reporters that the Mr. Biden’s biggest concern is releasing a package that is too small.

-

The president has been clear since long before he came into office that he’s open to engaging with both Democrats and Republicans in Congress about their ideas. And this is an example of doing exactly that. So as we said in our statement last night, it’s an exchange of ideas, an opportunity to do that. This group obviously sent a letter with some outline, some top lines of their concerns and their priorities, and he’s happy to have a conversation with them. What this meeting is not, is a forum for the president to make or accept an offer. His view — it remains — what was stated in the statement last night, but also what he said on Friday, which is that the risk is not that it is too big, this package, the risk is that it is too small. And that remains his view, and it’s one he’ll certainly express today. But it’s important to him that he hears this group out on their concerns, on their ideas. He’s always open to making this package stronger. And he also, as was noted in our statement last night, remains in close touch with Speaker Pelosi with Leader Schumer, and he will continue that engagement throughout the day, and in the days ahead.

White House officials offered a pointed, if polite, warning to 10 Senate Republicans planning to pitch a scaled-back coronavirus relief package to President Biden at the White House on Monday evening: Think bigger.

Jen Psaki, the White House press secretary, played down expectations of the meeting, a critical first test of Mr. Biden’s dueling commitments to bipartisanship and speeding pandemic aid, saying no deal would be done without further negotiations — a statement aimed at reassuring Democrats leery of a fast, weak deal.

“What this meeting is not is a forum for the president to make or accept an offer,” Ms. Psaki told reporters on Monday afternoon, repeating the president’s determination to push through a $1.9 trillion stimulus bill.

“The risk is not that it is too big, this package,” Ms. Psaki added. “The risk is that it is too small. That remains his view.”

A coalition of center-right Republican senators, led by Susan Collins of Maine, on Monday outlined a more limited $618 billion stimulus plan, which they are billing as a way for Mr. Biden to pass a pandemic aid bill with bipartisan support and make good on his inauguration pledge to unite the country.

With 10 Republicans on board, joining the Senate’s 50 Democrats, a bipartisan bill could overcome the chamber’s 60-vote filibuster rule. But Democrats have shown little enthusiasm for a measure that amounts to less than one third of what the president says is needed.

Still, after receiving a letter from the senators on Sunday requesting a meeting, Mr. Biden called Ms. Collins and invited her and the other signers to the White House. He also spoke with Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California and Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the majority leader.

The Republican proposal is likely to be met with resistance from congressional Democrats, who are preparing this week to begin laying the groundwork for passing Mr. Biden’s plan through a process known as budget reconciliation, which would allow it to bypass a filibuster and pass solely with Democratic votes.

The proposal would include $160 billion for vaccine distribution and development, coronavirus testing and the production of personal protective equipment; $20 billion toward helping schools reopen; more relief for small businesses; and additional aid to individuals. The package would also extend enhanced unemployment benefits of $300 a week — currently slated to lapse in March — until June 30.

“We recognize your calls for unity and want to work in good faith with your administration,” wrote the Republican group, which includes Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Mitt Romney of Utah.

The measure omits a federal minimum wage increase that Mr. Biden included in his plan. It would also whittle down his proposal to send $1,400 checks to many Americans, and limit it to lower-income earners.

The proposal calls for checks of up to $1,000 for individuals making $50,000 a year or less and families with a combined income of up to $100,000, with individuals earning less than $40,000 — and families earning less than $80,000 — receiving the full amount.

Previous rounds of direct payments were targeted to Americans earning less than $99,000 annually, with those earning less than $75,000 receiving the full amount.

Congress approved more than $4 trillion through a series of bills last year to address the coronavirus crisis and its economic fallout. Most recently, in December, lawmakers passed a $900 billion stimulus plan that included $600 direct checks to many Americans.

Mr. Biden received an important boost on Monday ahead of his meeting with the senators: Gov. Jim Justice of West Virginia, a close ally of former President Trump, said he supported a bigger relief package than the one that the center-right Republicans are proposing.

“If we actually throw away some money right now, so what?” said Mr. Justice, a former Democrat who switched parties to support Mr. Trump in 2017, told CNN.

The American economy will return to its pre-pandemic size by the middle of this year, even if Congress does not approve any more federal aid for the recovery, but it will be years before everyone thrown off the job by the pandemic is able to return to work, the Congressional Budget Office projected on Monday.

The new projections from the office, which is nonpartisan and issues regular budgetary and economic forecasts, are an improvement from the office’s forecasts last summer. Officials told reporters on Monday that the brightening outlook was a result of large sectors of the economy adapting better and more rapidly to the pandemic than originally expected.

They also reflect increased growth from a $900 billion economic aid package that Congress passed in December, which included $600 direct checks to individuals and more generous unemployment benefits.

The budget office now expects the unemployment rate to fall to 5.3 percent at the end of the year, down from an 8.4 percent projection last July. The economy is expected to grow 3.7 percent for the year, after recording a much smaller contraction in 2020 than the budget office initially expected.

The rosier projections are likely to inject even more debate into the discussions over whether to pass President Biden’s $1.9 trillion economic rescue package. It could embolden Republicans who have pushed Mr. Biden to scale back the plan significantly, saying the economy does not need so much additional federal support and that another big package could “overheat” the economy.

But the report shows little risk of that happening. The economy is projected to remain below potential levels until 2025 on its current path. And big economic risks remain. The number of employed Americans will not return to its pre-pandemic levels until 2024, officials predicted, reflecting the prolonged difficulties of shaking off the virus and returning to full levels of economic activity.

The Federal Reserve chair, Jerome H. Powell, warned last week that the economy was “a long way from a full recovery” with millions still out of work and many small businesses facing pressure.

Budget officials said the rebound in growth and employment could be significantly accelerated if public health authorities were able to more rapidly deploy coronavirus vaccines across the population.

As it stands, the budget office sees little evidence of growth running hot enough in the years to come to spur a rapid increase in inflation. It forecast inflation levels below the Federal Reserve’s target of 2 percent for years to come, even with the Fed holding interest rates near zero.

Other independent forecasts, including one from the Brookings Institution last week, have projected that another dose of economic aid — like the $1.9 trillion package Mr. Biden has proposed — would help the economy grow more rapidly, topping its pre-pandemic path by year’s end.

During January, the pandemic’s deadliest month, Laredo, Texas, held the bleak distinction of having one of the most severe outbreaks of any city in the United States. The death toll in the overwhelmingly Latino city of 277,000 now stands at more than 630 — including at least 126 in January alone.

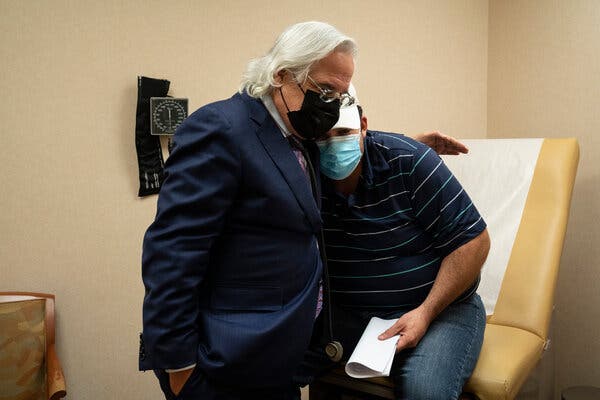

When the virus made its way to the borderlands almost a year ago, Dr. Ricardo Cigarroa could have just hunkered down. He could have focused on his profitable cardiology practice, which has 80 employees. He could have kept quiet.

Instead, Dr. Cigarroa has become a top crusader and the de facto authority on the pandemic along this stretch of the U.S.-Mexico border.

On regional television stations, he calmly explains, in both English and Spanish, how the virus is evolving. Known for making Covid-19 house calls around Laredo in his old Toyota Tacoma pickup, he is interviewed so often that Texas Monthly called him “The Dr. Fauci of South Texas,” comparing him to Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the country’s top infectious disease expert — though Dr. Cigarroa holds no official government portfolio.

Lately, Dr. Cigarroa has been losing his patience.

Looking exhausted in a video posted on Facebook, he blasted political leaders for allowing the virus to rampage through this part of South Texas. Dr. Cigarroa singled out Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, for refusing to allow Laredo to impose stricter mitigation measures.

“To the governor: It’s OK to swallow your pride,” Dr. Cigarroa said, stunning some viewers with a warning that the virus could kill 1 in 250 Laredoans by midyear. “It’s OK to say that you’re not going to do it, and then do it to save lives.”

Pleading with the people of Laredo to consider civil disobedience in the form of staying home from work if politicians fail to act, he added, “The only thing that will save lives at this point will be staying home and shutting down the city.”

Even as more districts reopen their buildings and President Biden joins the chorus of those saying schools can safely resume in-person education, hundreds of thousands of Black parents say they are not ready to send their children back. That reflects both the disproportionately harsh consequences the coronavirus has visited on nonwhite Americans and the profound lack of trust that Black families have in school districts, a longstanding phenomenon exacerbated by the pandemic.

It also points to a major dilemma: School closures have hit the mental health and academic achievement of nonwhite children the hardest, but many of the families that education leaders have said need in-person education the most are most wary of returning.

That is shifting the reopening debate in real time. In Chicago, only about a third of Black families have indicated they are willing to return to classrooms, compared with 67 percent of white families, and the city’s teachers’ union, which is hurtling toward a strike, has made the disparity a core part of its argument against in-person classes.

In New York City, about 12,000 more white children have returned to classrooms than Black students, though Black children make up a larger share of the overall district. In Oakland, Calif., just about a third of Black parents said they would consider in-person learning, compared with more than half of white families. And Black families in Washington, Nashville, Dallas and other districts also indicated they would keep their children learning at home at higher rates than white families.

Education experts and Black parents say decades of racism, institutionalized segregation and mistreatment of Black children have left Black communities to doubt that school districts are being upfront about the risks.

“For generations, these public schools have failed us and prepared us for prison, and now it’s like they’re preparing us to pass away,” said Sarah Carpenter, the executive director of Memphis Lift, a parent advocacy group in Tennessee. “We know that our kids have lost a lot, but we’d rather our kids to be out of school than dead.”

In many cities and districts, Latino and Asian-American families are also less likely than white families to send their children back. Asian-Americans have opted out of in-person classes at the highest rates of any ethnic group in New York City. Latino families in Chicago were most likely to say they would keep their children at home when schools reopened.

Still, the pattern is most consistent and pronounced with Black families, which have been particularly affected by decades of underinvestment. By one estimate, a $23 billion gap, or $2,226 per pupil, separates funding for predominantly white districts and nonwhite districts, and Jessica Calarco, a sociologist at Indiana University Bloomington who has studied reopening, said the pandemic had amplified that inequity.

“If you know your school doesn’t have hot running water, how would you feel about sending your child to that school knowing they can’t fully wash their hands before they eat lunch?” she asked.

GLOBAL ROUNDUP

A million doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine arrived in South Africa on Monday, paving the way for the country to begin vaccinating its population of nearly 60 million. Health care workers will be the first to be offered the shots, officials said.

The country has reported by far the most cases and deaths from the coronavirus on the African continent. It has participated in clinical trials of several vaccines.

The plane delivering the eagerly awaited doses from the Serum Institute of India, which produced them, was met at the airport by President Cyril Ramaphosa. The president has come under criticism over the country’s lagging start to widespread vaccination, with many countries in Asia and the West able to start immunizing their populations weeks before South Africa could secure a supply.

Health officials have said that it could take up to two more weeks before the country begins widely administering the doses that arrived on Monday.

South Africa experienced a surge in new cases around the turn of the year, fueled by the more transmissible variant of the virus that was first detected in the country. But the surge has begun to ease in recent weeks. Information has not yet been released on the AstraZeneca vaccine’s effectiveness against the variant, which is now predominant in the country.

Over the course of the pandemic, South Africa has reported about 1.45 million cases, and has lately been averaging about 5,800 new cases a day, according to a New York Times database.

In other developments around the world:

-

Seeking a better understanding of the pandemic’s origins, a team of 15 World Health Organization experts is visiting some of the places first hit by the coronavirus in the Chinese city of Wuhan, including a live animal market, a hospital and a disease control center. The inquiry is expected to take months to complete. Scientists initially believed the outbreak began at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, but many experts now doubt that theory.

-

The European Union will get 75 million additional doses of vaccine in the next few months, the German pharmaceutical company BioNTech announced on Monday. The vaccine jointly developed by the company and Pfizer was the first to be authorized for use in the E.U., but supplies have been limited by production issues in the early going, and several countries, including Germany, are off to slower than expected starts in vaccinating their populations.

-

The police in China said they had broken up a criminal ring that manufactured and sold more than 3,000 fake coronavirus vaccine doses, the state-run Xinhua news agency reported on Monday. More than 80 people were arrested, the agency said. According to Xinhua, the police said that since September, the main suspect had been selling vials of “vaccine” that was really just saline solution.

The scattered reports from around the country can play like a cruel irony: Someone tests positive for the coronavirus even though they have already received one or both doses of a Covid-19 vaccine.

Notable examples

It’s happened to at least three members of Congress recently:

But it’s been reported in people in other walks of life too, including Rick Pitino, a Hall of Fame basketball coach, and a nurse in California.

How can that happen?

Experts say cases like these are not surprising and do not indicate that there was something wrong with the vaccines or how they were administered. Here is why.

-

Vaccines don’t work instantly. It takes a few weeks for the body to build up immunity after receiving a dose. And the vaccines now in use in the U.S., from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna, both require a second shot a few weeks after the first to reach full effectiveness.

-

Nor do they work retroactively. You can already be infected and not know it when you get the vaccine — even if you recently tested negative. That infection can continue to develop after you get the shot but before its protection fully takes hold, and then show up in a positive test result.

-

The vaccines prevent illness, but maybe not infection. Covid vaccines are being authorized based on how well they keep you from getting sick, needing hospitalization and dying. Scientists don’t know yet how effective the vaccines are at preventing the coronavirus from infecting you to begin with, or at keeping you from passing it on to others. (That’s why vaccinated people should keep wearing masks and maintaining social distance.)

-

Even the best vaccines aren’t perfect. The efficacy rates for Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines are extremely high, but they are not 100 percent. With the virus still spreading out of control in the U.S., some of the millions of recently vaccinated people were bound to get infected in any case.

The deputy commissioner for public health at the New York State Health Department resigned in late summer. Soon after, the director of its bureau of communicable disease control also stepped down. So did the medical director for epidemiology. Last month, the state epidemiologist said she, too, would be leaving.

The high-level departures came as morale plunged in the Health Department and senior health officials expressed alarm to one another over being sidelined and treated disrespectfully, according to five people with direct experience inside the department.

Their concern had an almost singular focus: Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo.

Even as the pandemic continues to rage and New York struggles to vaccinate a large and anxious population, Mr. Cuomo has all but declared war on his own public health bureaucracy. The departures have underscored the extent to which pandemic policy has been set by the governor, who with his aides designed a vaccination program hampered by early delays.

The troubled rollout came after Mr. Cuomo declined to use the longstanding vaccination plans that the State Department of Health had developed in recent years in coordination with local health departments. Mr. Cuomo instead adopted an approach that relied on large hospital systems to coordinate vaccinations.

In recent weeks, the governor has repeatedly made it clear that he believed he had no choice but to seize more control over pandemic policy from state and local public health officials, who he said had no understanding of how to conduct a real-world, large-scale operation like vaccinations. After early problems, in which relatively few doses were being administered, the pace of vaccinations has picked up and New York is now roughly 20th in the nation in percentage of residents who have received at least one vaccine dose.

“When I say ‘experts’ in air quotes, it sounds like I’m saying I don’t really trust the experts,” Mr. Cuomo said at a news conference on Friday, referring to scientific expertise at all levels of government during the pandemic. “Because I don’t. Because I don’t.”

His comments reflected a rift between the state’s top elected official and its career health experts of the sort that has occurred across different levels of government during the pandemic.

In Albany, tensions worsened in recent months as state health officials said they often found out about major changes in pandemic policy only after Mr. Cuomo announced them at news conferences — and then asked them to match their health guidance to the announcements.

That was what happened with the vaccine plan, when state health officials were blindsided by the news that the rollout would be coordinated locally by hospitals.

At least nine senior state health officials have left the department, resigned or retired in recent months. They include Dr. Elizabeth Dufort, the medical director in the division of epidemiology; and Dr. Jill Taylor, the head of the renowned Wadsworth laboratory — which has been central to the state’s efforts to detect virus variants — and the executive in charge of health data, according to state records.